IF YOU’VE STOOD IN front of the Lincoln Monument at the southern entrance to Chicago’s Lincoln Park, you’ve caught something of the burden that must weigh on those called to change the world. The statue captures the President stepping forward to address the nation in the midst of the Civil War. His head hangs low and his eyes are weary.

On ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s last day in Chicago — May 5, 1912 — he spent some time in the morning with children who had gathered at the Plaza Hotel, and walked with them into the park to be photographed. Then he said that he wanted to be alone. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá left the group and paced down toward the entrance of Lincoln Park. There he stood gazing up at the sixteenth President cast in bronze.

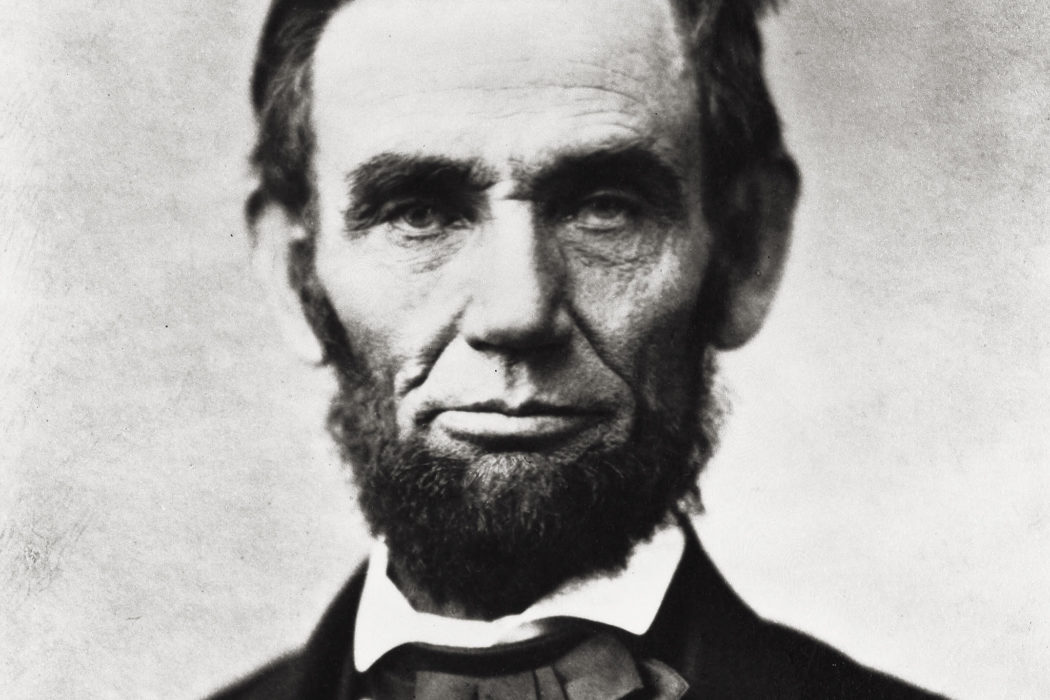

President Abraham Lincoln was, by most accounts, a humble man of God. One of his aides wrote: “Benevolence and forgiveness were the very basis of his character.” Yet he had little time for religion. “He never uttered a prayer in public,” another aide said. “Yet prayers for him fastened our cause daily with golden chains around the feet of God.”

Lincoln, for his part, recalled the prayers his mother spoke to him as a child, noting in a poignant turn of phrase: “they have clung to me all my life.” His gift for words drove his political career, even as his unwavering moral compass set him apart from his chosen profession.

“A house divided against itself cannot stand.” So Lincoln declared to the 1858 Republican State Convention, in his hometown of Springfield, Illinois. He had borrowed Jesus’s statement from the Book of Matthew to stake out his position on the expansion of slavery in the United States. “I believe this government cannot endure, permanently half slave and half free.” He saw things with a simple, profound clarity that ‘Abdu’l-Bahá found missing in many of those who spoke from a podium or a pulpit.

Within two years Lincoln secured the Republican Presidential nomination here in Chicago, and went on to win the critical election of 1860. Seven southern states seceded from the Union before he could even take office. Just five years after that, America, with Lincoln at her helm, had traversed the greatest political, military, and moral crisis in its history.

Yesterday, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá visited Oak Woods Cemetery on Chicago’s South Side, to pray over the grave of Corinne True’s son, Davis. No doubt he would have paused to note the nearly 4,500 Confederate soldiers buried there beneath a towering monument. They had died as prisoners of war at Chicago’s Camp Douglas.

Today, a few hours after his quiet moment alone with the President, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá spoke to the congregation of All Souls Church. In 1905, the church, which didn’t have a building of its own, constructed the Abraham Lincoln Center, a settlement house serving “the advancement of the physical, intellectual, social, civic, moral and religious interests of humanity, irrespective of age, sex, creed, race, [or] condition of political opinion.”

‘Abdu’l-Bahá concluded his speech at All Souls with a prayer. It was about unity:

“O Thou kind Lord! Thou hast created all humanity from the same stock. Thou hast decreed that all shall belong to the same household . . . . O Thou kind Lord! Unite all. Let the religions agree and make the nations one, so that they may see each other as one family and the whole earth as one home.”