ONE MORNING AFTER HIS talk at the Lake Mohonk Conference on International Arbitration, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá took a walk with some friends near the Mountain House, where the conference was held. The group came upon a party of young people. After a few words of greeting ‘Abdu’l-Bahá said that he would recount a fable he had heard in the East.

Howard Colby Ives, a Unitarian minister from New Jersey, reported the occasion twenty-five years later in his book, Portals to Freedom. The earliest known version of the story ‘Abdu’l-Bahá told, which is often attributed incorrectly to Aesop, is from an Old Syriac manuscript of Kalilah and Dimnah—a book of fables of Indian or Persian origin that Ibn al-Mukaffa translated into Arabic around AD 750. William Langland included a version of it in Piers Plowman, his allegorical narrative poem from the late fourteenth century, calling it “The Parliament of the Rats and Mice.”

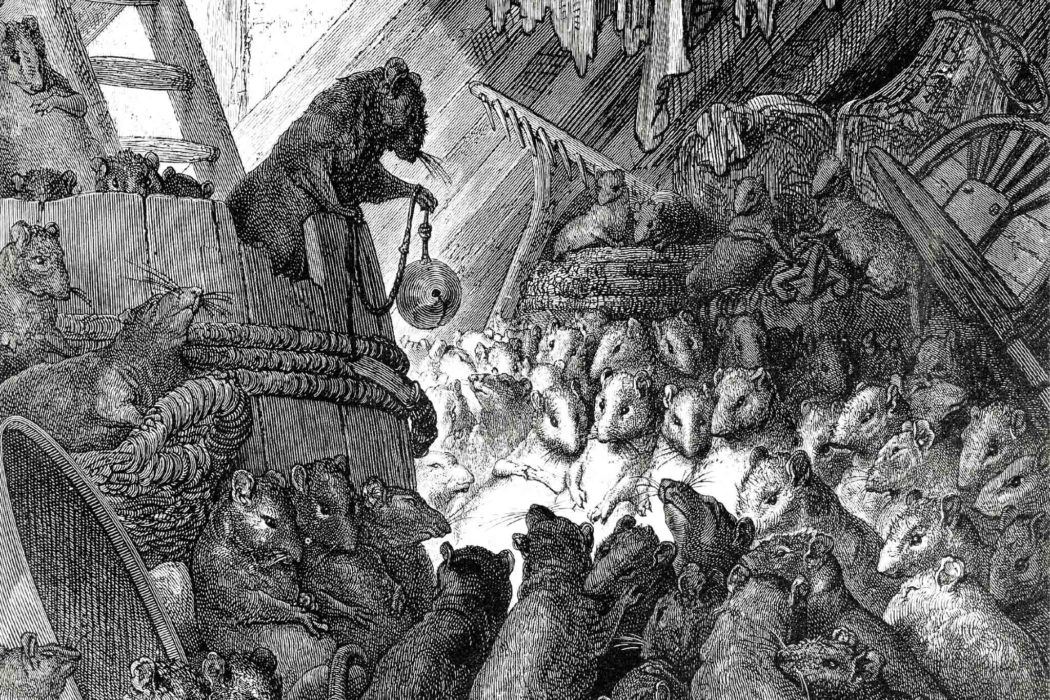

Once upon a time, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá narrated, the rats and mice held an important conference, the subject of which was to make peace with the cat. The cat, Langland wrote, “came whenever he liked and leapt on them easily and seized them at his will, and played with them perilously and batted them about.”

“A rat of renown, most eloquent of speech,” Langland continues, “presented an excellent remedy to them all. ‘I have seen men in the city of London wearing bright necklaces around their necks, and some craftily worked collars. They go about unleashed both in warren and wasteland wherever they like, and elsewhere at other times, as I hear tell. Were there a bell on their necklace, by Jesus, it seems to me that men might know where they were and run away.’ ”

“ ‘And so,’ ” said the rat, “ ‘reason tells me to buy a bell of brass or bright silver and fasten it on a collar for our common good and hang it on the cat’s neck; then we can hear whether he rides, rests, or roams about to play. If he wishes to amuse himself, then we can appear in his presence, and if he is angry, we can be wary and shun his way.’ ”

This seemed like an excellent plan, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá explained, until the question arose as to who should undertake the dangerous job of belling the cat. None of the rats liked the idea and the mice thought they were altogether too weak. So the conference broke up in confusion.

“Everyone laughed,” Ives tells, “‘Abdu’l-Bahá with them. After a short pause he added that that is much like these Peace Conferences. Many words, but no one is likely to approach the question of who will bell the Czar of Russia, the Emperor of Germany, the President of France and the Emperor of Japan.”

“Faces were now more grave,” Ives wrote.

“It is very easy to come here,” ‘Abdu’l-Bahá concluded, “camp near this beautiful lake, on these charming hills, far away from everybody and deliver speeches on Universal Peace. These ideals should be spread and put in action over there, (Europe) not here in the world’s most peaceful corner.”