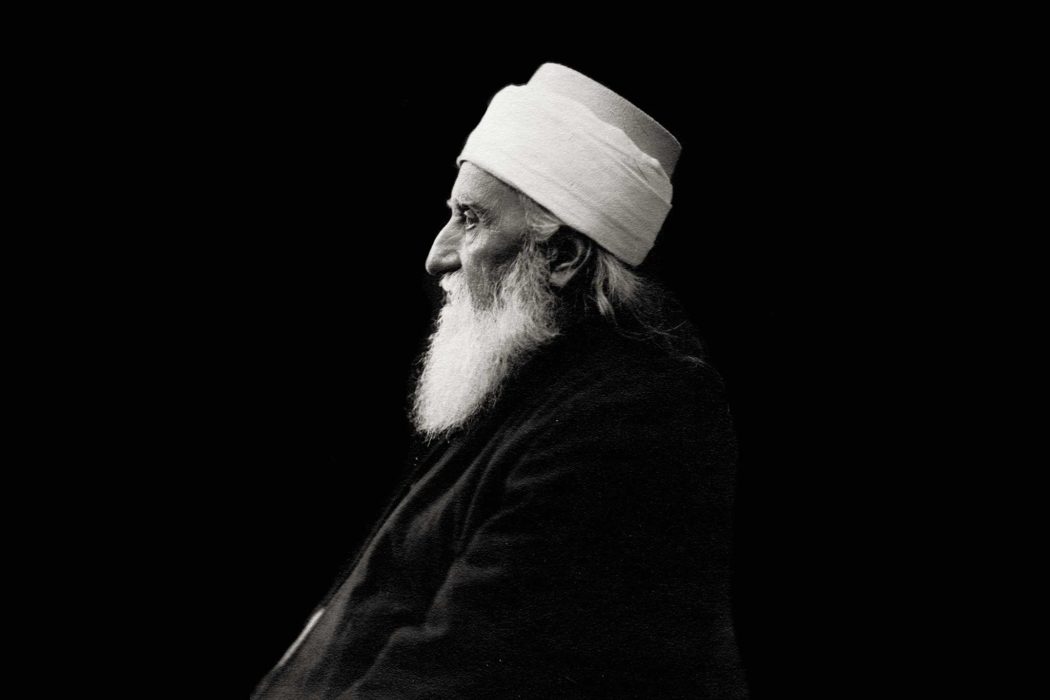

THE MOST EXTENSIVE PRIMARY sources for ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s journey across North America in 1912 come with difficult problems. If you were to ask Mahmúd-i-Zarqání how Americans responded to ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, you might always get the same answer. They were — almost every one of them — “astonished” at what they saw and heard from the Master. Mahmúd was a devoted follower on unfamiliar terrain in America, who felt the greatest reverence for ‘Abdu’l-Bahá and held him in awe. In his preface he writes that he generally found himself overwhelmed by the events he saw, and in his account he ascribes such wonder to everyone.

Juliet Thompson’s ‘Abdu’l-Bahá is an otherworldly figure whose every look, every slight gesture, is imbued with a magical quality that she flourishes with her own emotions. How close was the real ‘Abdu’l-Bahá to Juliet’s perception of him? It is difficult to say.

Reverend Howard Colby Ives wrote an autobiography of his time with ‘Abdu’l-Bahá called Portals to Freedom. Its pages are filled with turns of phrase that mix metaphors and burst with personal drama, yet he seems deeply sincere and his story often brings one eerily close to ‘Abdu’l-Bahá. The scene he paints of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá wiping the tears from his eyes on April 12 at the Hotel Ansonia in New York is so moving that it’s hard not to well up with tears yourself.

Agnes Parsons wrote a nuts-and-bolts diary account of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in Washington and Dublin, full of interesting details but largely free of the romantic aura that surrounds Thompson’s and Ives’s accounts. But Agnes’s social circle constrains her perspective. She hosts ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in her home and plans many of his activities, but when he attends events in Washington with African Americans, you wouldn’t know from her diary that they carried any significance.

Journalists portray ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in a variety of ways. Their first impressions are sometimes shaped by Orientalist ways of thinking that cause them to see him and his retinue of Persians as strange and foreign: such is Nixola Greeley-Smith’s article in the New York World on ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s second day in America. But very quickly these reporters see something new in this visitor that upsets their preconceptions: a man who turns out to be more modern, aware, and active than they have been trained to expect. Kate Carew’s Sunday magazine profile of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in the New-York Tribune so skillfully combines the light sarcasm of her gossipy style with such an obvious respect for her subject that it seems she must have known a great deal about ‘Abdu’l-Bahá before she ever set foot in the Hotel Ansonia.

The memoirs that recount ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s journey focus so deeply on him as their subject that they isolate him from the bustling reality around him. In these accounts there seems to be little else going on in America, this rising industrial nation of a hundred million people, other than the talks he gives and the meetings he holds. In 239 Days in America, we have sought to embed ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in a rich context of time and place, and to see what this context reveals.

On one hand this means examining the larger issues that define American life, such as the stunning reality of race. On the other, it means realizing that many of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s statements, even small ones, were spoken with a keen sense of what was happening around him: the murmurs in the room, the stories that day in the newspaper, the other half of the conversation that was never recorded. To find more of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, you sometimes have to put that stuff back in.

We hope this approach not only makes ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s journey in America seem more vivid, but also helps us make clearer connections between what he said in 1912 and today’s pressing issues.