THE CAR APPROACHED FROM the direction of Kittery, slowed as it reached the streetcar depot at the top of Green Acre’s long driveway, and then stopped. While a tall man with dark hair kept watch in the front seat, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá got into the back, and sat next to Miss Sarah J. Farmer. It was Tuesday, August 20, 1912, and she had not set eyes on Green Acre for more than three years. The trouble had started way back during the 189os. The problem was that she was a woman.

In 1889, Sarah Farmer signed on as silent partner in the Eliot Hotel Company. Four local men had started the venture to capture the tourists flocking to nearby York Beach. But somehow the partners had overlooked the fact that Eliot was six miles from the sea, and the enterprise failed. They were therefore delighted, when, in 1894, Miss Farmer proposed to lease the boarded-up hotel each summer for a few weeks of lectures on religion.

Within two years, thousands of people were attending each July and August, and newspapers across the Northeast followed the proceedings. Sarah J. Farmer secured the leading public intellectuals of the era to speak at Green Acre, transforming it from a center for inter-religious dialogue into a place that encompassed the social and intellectual movements that were on the verge of launching the Progressive Era.

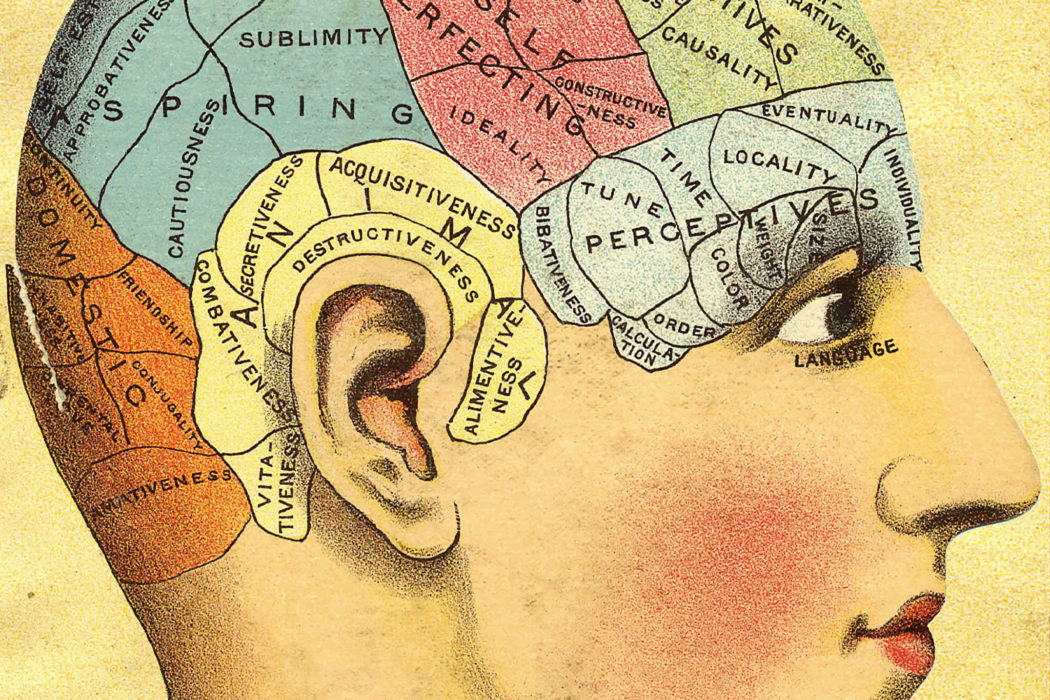

Even the phrenologists got in on it. The Phrenological Journal measured Sarah Farmer’s scalp with calipers for its August, 1899, issue. The so-called scientists who practiced phrenology believed that personality traits, such as Combativeness, Benevolence, and Spirituality, lodged in certain parts of the brain, and could be determined by measuring skulls. The qualities they imprinted on Miss Farmer indicate the esteem in which she was held by the thinking classes in New England:

“Miss Farmer, as her profile picture indicates, has a large development of Firmness, which gives her a persistency of purpose which is not easily overcome by the persuasions or arguments of others. . . .” “She has a keen ambition to excel,” they wrote, “and possesses a self-possession which knows no trifling or lowering of her standard.”

But not everyone was delighted by Miss Farmer’s persistence, especially not the powerful men whose fringe interests found new life among her largesse at Green Acre. Many of the speakers made money off the lecture circuit, but Sarah Farmer insisted that the programs at Green Acre be free to all. Carried along by her Transcendentalist optimism, she had assumed full financial responsibility for everything, confident that her commitment would attract comparable support from collaborators. Instead, speakers, their families, and even attending guests assumed that their accommodations should be free of charge, too — which Sarah Farmer paid for.

Another problem was that they were indebted for their success to a woman. At the age of fifty-one Sarah Farmer was unmarried, having turned down eighteen proposals of marriage and broken three engagements. Unlike many of her contemporaries, such as Jane Addams, she didn’t work primarily in the fields of social action common among women, such as child welfare, temperance, or urban reform. Instead, Sarah J. Farmer had decided to shape directly the male-dominated strands of thought that emerged from New England’s intellectual elites..

Many people tried to convince Sarah Farmer that the high ideals on which she ran Green Acre were unrealistic, but she pushed back. “With regard to forming a corporation at Green Acre,” she wrote, “that cannot be. It has been suggested three times, and it has nearly crushed the life out of the work. The moment that a corporation gains possession, the Spirit of Green Acre is gone.”

At the same time, she encountered growing intellectual opposition from associates like Lewis Janes, the man she had hired to run her school of comparative religion, whose formalistic academic approach made no room for the primarily moral and social passions that preoccupied her. “I regret exceedingly this difference of understanding,” Janes wrote to her, “which could never have occurred between two men accustomed to business matters.” By 1898 the forum was in financial collapse.

Her business partners decided enough was enough, and summoned her to a meeting in December, 1899, where they planned to force her to sell the property. Instead of giving her their ultimatum, they received unexpected news: Miss Farmer had sailed for Europe.

This is the first of a two-part feature on the life of Sarah J. Farmer. Read Part Two here: Sarah J. Farmer: One Of America’s Great Religious Innovators