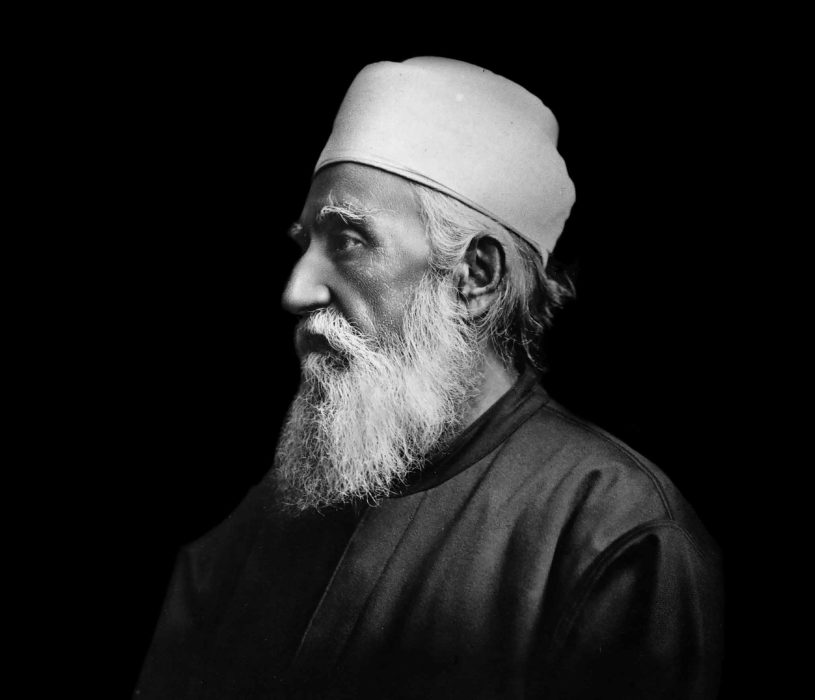

“UPON THE FACES OF those present,” ‘Abdu’l-Bahá said as he looked out at the crowd, “I behold the expression of thoughtfulness and wisdom.” It was August 27, 1912, and he was speaking to the Metaphysical Club of Boston. The organization, which had been meeting for about seventeen years, devoted itself to an exploration of the relationship between the physical matter and abstract realities. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá gave a talk that gracefully united the two.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá began by discussing the interconnectedness of matter at the atomic level. It was an extremely timely illustration, since British physicist Ernest Rutherford had discovered the atomic nucleus the year before. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá noted that the smallest of particles are in a state of “perpetual motion, undergoing continuous degrees of progression.” A single atom, he said, can progress through the mineral world, into the vegetable world, the animal world, and even the human world. As atoms progress, he stated, they become “imbued with the powers and virtues,” as well as “the attributes and qualities,” of whatever category they embody.

“It is evident,” ‘Abdu’l-Bahá concluded, “that each elemental atom of the universe is possessed of a capacity to express all the virtues of the universe.” He was claiming the essential oneness of everything in existence. He then argued that God is the power that underlies and animates these transformations. “The origin and outcome of phenomena,” he said, “is the omnipresent God; for the reality of all phenomenal existence is through Him.”

‘Abdu’l-Bahá turned his attention to the human world. “This human plane,” he stated, “is one creation, and all souls are the signs and traces of the divine bounty.” The implication, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá noted, is that no one could be rejected. “In this plane there are no exceptions,” he said.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá then laid out for his audience at the Metaphysical Club the responsibility this places on each of them. “Some souls are weak,” he said, “we must endeavor to strengthen them.” He added: “Some are ailing; we must seek to restore them to health.” It may have sounded obvious enough to those assembled that evening, but in an America where Social Darwinism was beginning to take root in both economics and the social sciences, and where eugenics was seriously debated by mainstream intellectuals, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá was making a clear statement.

“We must exercise extreme patience, sympathy and love toward all mankind,” he said, “considering no soul as rejected. If we look upon a soul as rejected, we have disobeyed the teachings of God.”