THE GRITTY CRUNCH OF the dirt road gave way to a rhythmic humming from the smooth bricks that paved the long driveway. Their tiny vibrations traveled along the axles of the rented automobile, through its iron chassis, and into the seat cushion on which ‘Abdu’l-Bahá sat. Trees lined the drive on either side, and at the top of the hill a mansion made of soft-toned red brick looked down across rolling countryside to the thickly wooded valley of nearby Antelope Creek. Fairview, the home of Mr. and Mrs. William Jennings Bryan, stood three miles south of Lincoln, Nebraska. It was the afternoon of Monday, September 23, 1912.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá had taken the train from Omaha to Lincoln, the capital of the state, to return the courtesy of Bryan’s visit to ‘Akká six and a half years earlier. “We called on Abbas Effendi as we were leaving Palestine,” Bryan had written from Vienna on June 5, 1906, in an article for the Chicago Daily News. He was traveling the lands of the Ottoman Empire and had stopped to visit ‘Abdu’l-Bahá who was still a prisoner in ‘Akká.

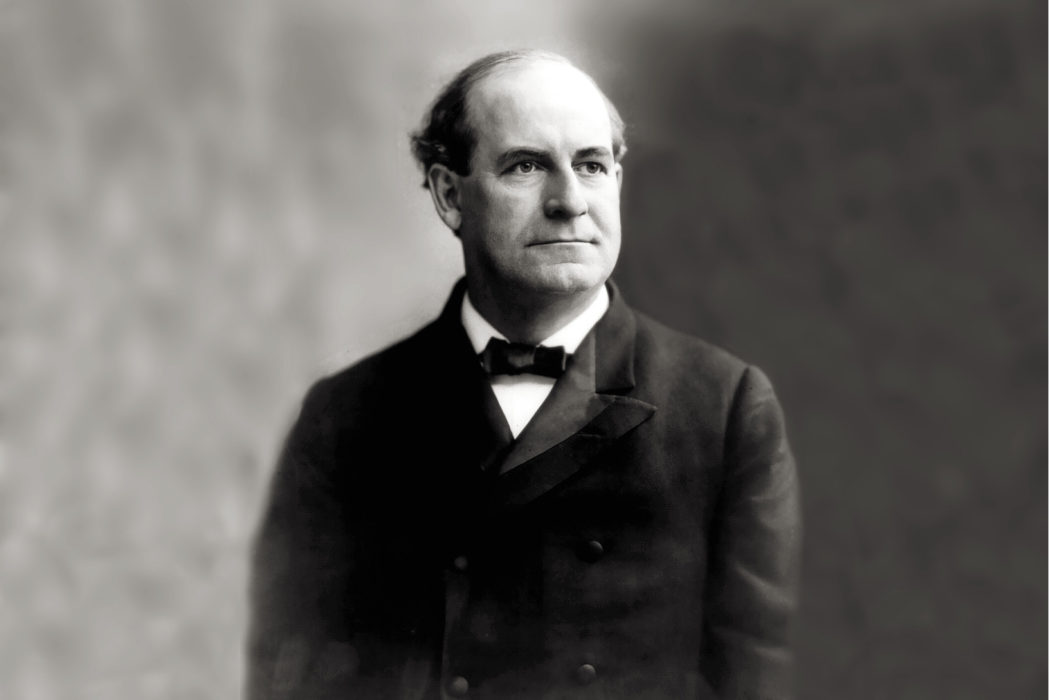

“The Great Commoner,” as William Jennings Bryan was known at home in America, had not been impressed with Sultan ‘Abdu’l-Hamíd II and the bureaucracy he ran. “The government of the sultan is the worst on earth,” he wrote. “It is more despotic than the Russian government ever was and adds corruption to despotism. . . . The sultan still rules by his arbitrary will, taking life or granting favor according to his pleasure. He lives in constant fear of assassination and yet he does not seem to have learned that his own happiness, as well as justice to the people, demands that the government shall rest upon the will of the governed.”

He found ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, whose teachings he likened to Tolstoy’s minus the strict pacifism, to be a welcome voice of reform. “How much he may be able to do in the way of eliminating the objectionable features of Mohammedanism no one can say,” Bryan thought, “but it is a hopeful sign that there is . . . an organized effort to raise the plane of discussion from brute force to an appeal to intelligence.”

‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s car pulled up in front of the house. Its design, Queen Anne combined with Classical Revival, sported a slate roof with protruding gables and dormer windows, cornices decorated with wooden saw-work, a tower with a bell-cast pyramid roof, and an enclosed reception room that had once been a windswept porch. Mrs. Bryan hurried toward the car to welcome her visitors, but her husband at that moment was 1300 miles away. Ever since returning in August from a vacation in the mountains with his wife, Bryan had spoken every day for seven weeks on the campaign trail for Woodrow Wilson. This week he had campaigned from the back of his train through the western states, speaking during short stops in towns like Bozeman, Montana; Pocatello, Idaho; and Ogden, Nevada.

Bryan arrived in Los Angeles at 7 a.m. on the 23rd, spoke twice in the morning, and then, not long before ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s car rode up the brick-paved driveway in Lincoln, he rose to address “the greatest outdoor political meeting that Los Angeles has ever known.” There, at Fiesta Park, the Los Angeles Times reported, the Great Commoner held an audience of 25,000 people spellbound with his “wonderful voice” and “magnetic eloquence” for more than two hours.

“The President has more power in his hand than any King, or Czar, or Emperor,” Bryan said at the close of his speech. Although he had taken a political side in this campaign — for Woodrow Wilson and against Roosevelt — some of what William Jennings Bryan said in Los Angeles about the moral qualifications for the Presidency resonated with much of what ‘Abdu’l-Bahá had argued about the responsibilities of those who held elective office. “When a frail human being is elevated to this supreme pinnacle of power,” Bryan declared, “he should tear from his breast every shred of ambition, and on his bended knees consecrate his term to his country’s service with no selfish purpose to blind his eyes or pervert his judgment. That is our idea of the Presidency.”

After having tea with Mrs. Bryan and her daughter, inspecting the library and Mr. Bryan’s study, and noting the large white head of a mountain goat that hung from one of Fairview’s walls, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá wrote a prayer in Persian for the Bryans, in the Great Commoner’s autograph book:

“O Lord!” he wrote. “Confirm this distinguished person in the greatest service to the human world, which is the unity of all mankind, that he may attain to Thy good pleasure in this world and obtain a bounteous portion from the surging ocean of Divine outpourings in this luminous age.”