THE LADDER THEY DROPPED was made from a thick cable of twisted hemp, with hard wooden slats for rungs.

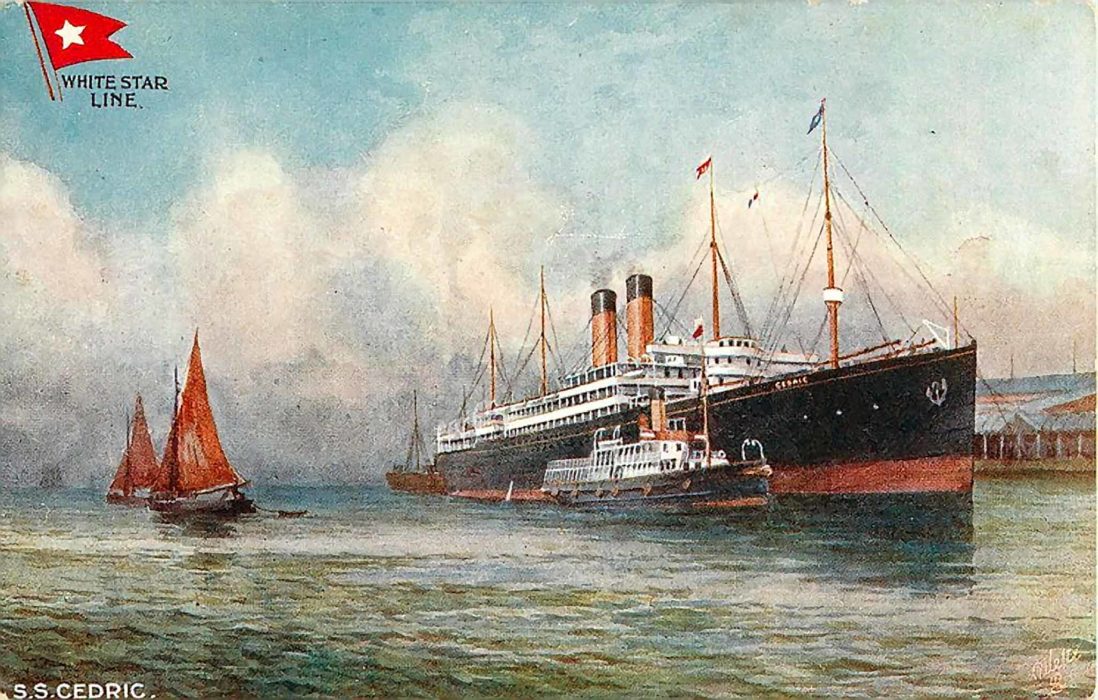

Wendell Phillips Dodge clung to it for dear life, twenty-five feet above the frigid waters of the bay. Beneath him a small steamship, a revenue cutter of the United States Treasury, rose and fell with the waves. Above him the sky surrendered to the black iron hull of a 21,000-ton oceangoing passenger liner, the Cedric of the White Star Line, which lay at anchor off Staten Island after steaming for sixteen days from Alexandria, Egypt. Its cargo: thousands of men, women, and children bound for New York.

Years from now he would be the press agent for David Belasco, America’s leading theatrical producer. But today Dodge was just a reporter, twenty-eight years old last August. He had hopped an early cutter at the ship news office in the Battery on this sparkling morning — April 11, 1912 — so he could get to the quarantine station on Staten Island before the Cedric passed the Narrows about 8 a.m. But typhoid fever and smallpox in the steerage had delayed the ship for three-and-a-half hours, while health inspectors offloaded 200 third-class passengers to the hospital on Hoffman Island and fumigated the ship. Now, just before noon, as he climbed the forty-seven feet to the Cedric’s main deck, Dodge could see dozens of tugs, barges, and ferries plying the harbor’s expanse. The great skyscrapers — some of them more than twenty stories high — had been reduced to a shadow rising half an inch above the northern horizon. He scrambled aboard, made his way through the passengers milling on deck, and set off to find his subject.

Dodge found the visitor standing on the deep forward balcony of the Cedric’s upper deck behind the pilothouse, surveying the panorama of the bay. He wore a long black cloak covering a robe of light tan: the colors identical to the Cedric’s massive twin funnels that towered above the ship behind him. His iron-grey head, capped with a white turban, was thrown back atop his shoulders like the rising steam. A cool wind came off the water and whipped around ‘Abdu’l-Bahá. To one side stood a short Persian man wearing intense dark eyes, a thick handlebar moustache and a black fez, waiting for him to speak. He was Dr. Ameen Fareed, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s translator.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá was already a well-known voice in the international peace movement. One reason he had crossed the ocean was to speak at the Lake Mohonk Conference on International Arbitration in May. He greeted the reporters and then invited them to join him in his stateroom. They crammed in, then peppered him with questions. As ‘Abdu’l-Bahá finished each sentence he waited for Fareed to interpret before moving on to the next one.

“Is it not possible that peace can become the means of trouble and war the means of progress?” one of the reporters asked.

“No,” ‘Abdu’l-Bahá replied. “It is war which is today the cause of all trouble. If all would lay down their arms, they would be freed from all difficulties and every misery would be changed into relief.” “What the people earn through hard labor is extorted from them by the governments and spent for purposes of war.”

The reporters in dark coats and derby hats jostled for space in the small first-class suite: it was a tiny space for a press conference. White wood paneling covered the upper walls of the sitting room, contrasting with dark wainscoting below. Through the door, in the sleeping cabin, a painted chrome bed frame occupied a quarter of the space, supporting a long narrow mattress. A small writing desk and chair stood next to it along the back wall, beside a tall, skinny armoire topped with a rectangular mirror. Along the opposite wall a long low sofa tucked itself under the window. An oriental rug covered the few remaining square feet of floor.

“What is your attitude toward woman suffrage?” another reporter asked. Emmeline Pankhurst’s hunger strike in London was all over the news.

“The modern suffragette is fighting for what must be,” Abdu’l-Bahá answered. “If women were given the same advantages as men, their capacity being the same, the result would be the same.”

Only the sound of scratching pencils interrupted the stream of words.

“The chief cause of the mental and physical inequalities of the sexes is due to custom and training, which for ages past have molded woman into the ideal of the weaker vessel.”

The Cedric started her engines for the final cruise up the bay. As she steamed north the city rose to meet her.

Back out on deck ‘Abdu’l-Bahá reached out toward the gigantic statue that now stood off to port, robed in green weathered copper, clutching a torch, and wearing a pointed crown. “Here is the new world’s symbol of liberty and freedom,” he said.

“After being forty years a prisoner I can tell you that freedom is not a matter of place. It is a condition. . . . When one is released from the prison of self, that is indeed a release.”

As the ship steamed up the Hudson, the journalists watched ‘Abdu’l-Bahá turn to starboard. He directed their attention to the cluster of towers in lower Manhattan ruled by the Singer Sewing Machine Building, the second-tallest building in the world. “These are the minarets of Western World commerce and industry,” he said. “The bricks make the house, and if the bricks are bad the house will not stand, as these do.”

Wendell Dodge scribbled away, taking down ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s concluding words for his story:

“It is necessary for individuals to become as good bricks, to eradicate from themselves race and religious hatred, greed and a limited patriotism, so that, whether they find themselves guiding the government or founding a home, the result of their efforts may be peace and prosperity, love and happiness.”

After a trip of twenty-five minutes or so, the Cedric reached Pier 59 at the end of West 18th Street on the north edge of Greenwich Village, where several hundred people awaited ‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Wendell Dodge left to file his story. It was syndicated by the Associated Press and wired, in shortened form, to news outlets across the country. When readers the next day picked up the New York Times or Tribune, the Detroit Herald, the Baltimore Sun, the Chicago Post, the Los Angeles Herald, or any one of dozens of other newspapers, they became among the first Americans to learn that ‘Abdu’l-Bahá was here.