FOURTEEN NEW YORK CHURCHES had vied to host ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s first public address in America. But the Reverend Dr. Percy Stickney Grant, Rector of the Church of the Ascension at Fifth Avenue and 10th Street in Greenwich Village, wasn’t in the habit of losing..

He was fifty-two. A mass of grey flames swept above his forehead, leaving white trails at the temples. Fervor peered out beneath a confident brow; resolve rode his ardent jawline. It was almost 11:30 a.m. on this Sunday, April 14, 1912, and Grant, engulfed in the singing voices of the choir and the thunder of the pipe organ, waited for the perfect moment in front of his congregation of 2000 people.

“Jesus lives! for us He died;

Then alone to Jesus living!”

His best side was his left side, not just in the pose he struck for cameras, but also when it came to his politics. The Social Gospel movement was alive and flourishing in America. Activist churchmen led social welfare campaigns for the poor, for the equalization of wealth, for the rights of exploited workers and minorities. This was tangible Christianity writ in modern terms; Grant and his church occupied its radical center.

“Pure in heart may we abide,

Glory to our Savior giving.”

“Hallelujah!”

Grant turned away from the congregation, walked back toward the altar, and disappeared into a doorway on the right side of the sanctuary. He returned a few moments later, hand-in-hand with ‘Abdu’l-Bahá.

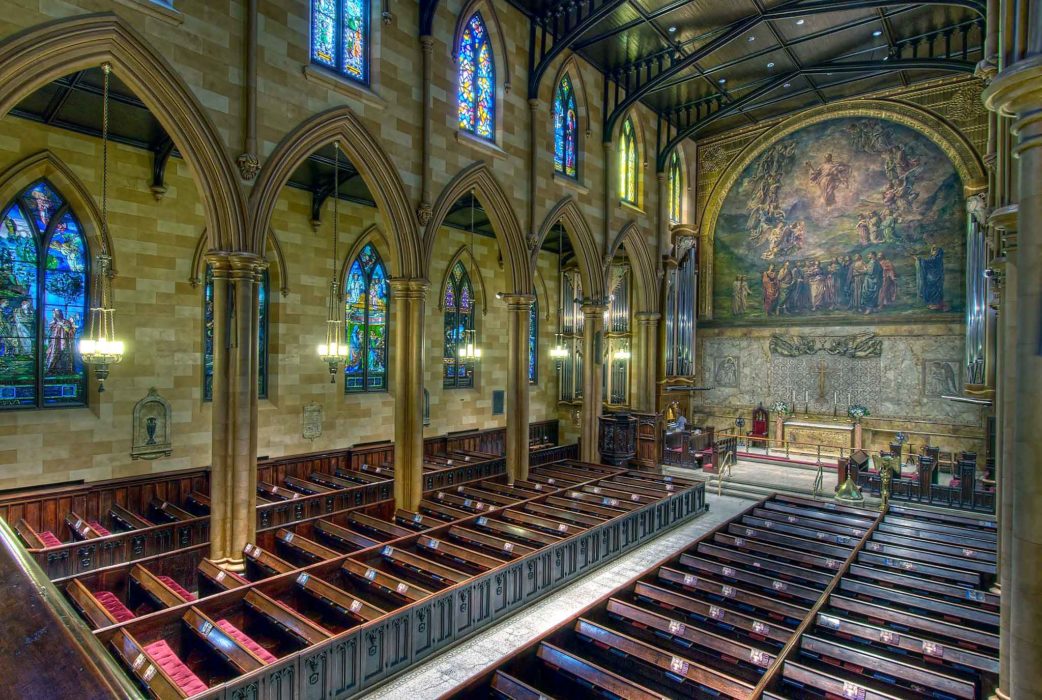

Last year, Grant had stood here one Sunday and denounced ‘Abdu’l-Bahá as a heathen and a threat to Christians. But today he had decked the chancel with calla lilies, and, to the right of the altar behind the railing, he had crowned the Bishop’s chair with a victor’s wreath of laurel leaves. He walked ‘Abdu’l-Bahá over to it, and, breaking the Nineteenth Canon of the Episcopal Church, invited him to be seated. Rules never stopped Percy Stickney Grant from making a point. When the organ fell silent he returned to the steps of the chancel.

“I have the honor and pleasure to welcome to this place of worship a messenger from the East,” he began. “He comes with a plan of construction and of reconstruction, and has brought to these shores a touchstone of love and of peace.”

“But, some will ask,” as indeed they already had, “‘What has he done to prove his sincerity?’ An exile from his native land from the age of nine; a prisoner for forty years, are the badges of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s sincerity.”

‘Abdu’l-Bahá rose, stepped forward, and replaced Grant on the chancel steps. He gazed out over the pews, packed to the aisles with parishioners, and began to speak.

“In his scriptural lesson this morning,” ‘Abdu’l-Bahá said, “the reverend doctor read a verse from the Epistle of St. Paul to the Corinthians, ‘For now we see through a glass, darkly; but then face to face.’”

After each sentence he paused, listening carefully as his translator, Dr. Fareed, rendered his words into English. “The light of truth has heretofore been seen dimly through variegated glasses, but now the splendors of divinity shall be visible through the translucent mirrors of pure hearts and spirits.”

‘Abdu’l-Bahá wore a cream-colored robe and a white turban. He stood on one side of the wide chancel table with Fareed on the other. Behind them a great canvas mural by John La Farge covered the upper half of the back wall, dominating the nave. Mary Magdalene and the eleven true Disciples, dressed in red, green, and gold, watched the risen Christ soar upward into heaven among a host of angels.

“Since my arrival in this country,” he said, “I find that material civilization has progressed greatly, that commerce has attained the utmost degree of expansion; arts, agriculture and all details of material civilization have reached the highest stage of perfection, but spiritual civilization has been left behind. Material civilization is like unto the lamp, while spiritual civilization is the light in that lamp.”

Percy Stickney Grant considered the delicate argument ‘Abdu’l-Bahá made, which resonated with his congregation. The imperative of the modern age, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá declared, is to establish international peace and reconciliation. Yet political power would never be equal to this task, for “the political interests of nations . . . are divergent and conflicting.” Faith in cultural and national identities would similarly fail, because “The very nature of racial differences and patriotic prejudices prevents . . . unity and agreement.” Only a new morality, rooted not in material concepts but in a holistic view of human nature, like that which Jesus taught, could establish the foundations needed for a just and unified world.

When he had finished speaking, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá offered a prayer for the congregation, returned to his seat, left a bill in the collection plate, and, at Grant’s request, delivered the final benediction.