MYRON H. PHELPS WAS ONE of the first Americans to meet ‘Abdu’l-Bahá. He was a wealthy New York lawyer, who had converted to Buddhism in India. Religion fascinated him, so when he heard that a new one had sprung up in Persia, and its leader lived in ‘Akká, Palestine, he made plans to visit him. After spending a month in ‘Akká, Phelps wrote the first book ever published in English about ‘Abdu’l-Bahá: Life and Teachings of Abbas Effendi.

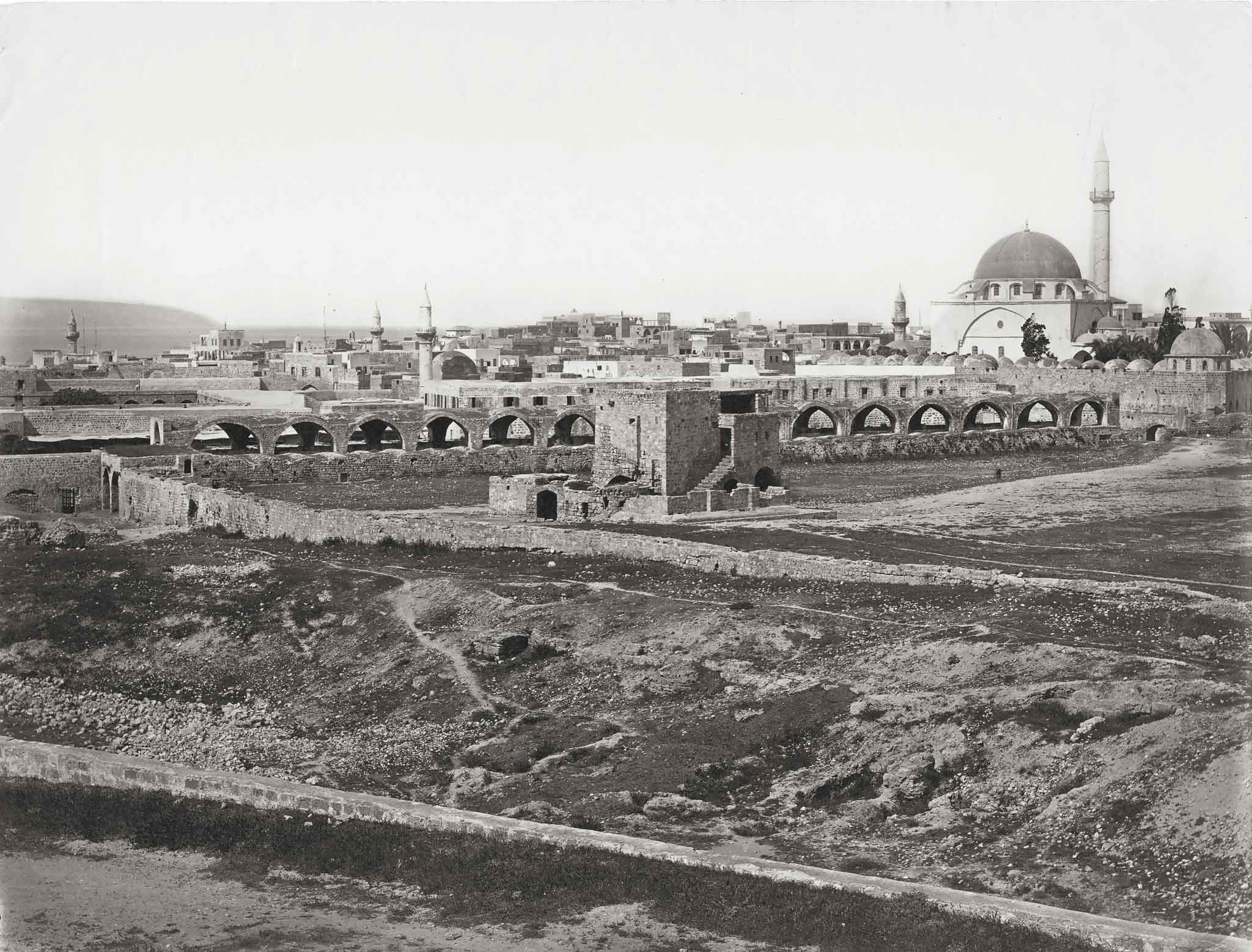

The year was 1902. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá had been confined in ‘Akká, the desolate penal colony of the Ottoman Empire, for the past thirty-four years. The whole city was a prison, cut off by desert on one side and the sea on the other. Nothing grew within the city’s walls, and it smelled so foul that they used to say that any bird flying over ‘Akká would drop dead from the stench. The empire’s worst criminals fended for themselves in the hard streets, carrying on as best they could as peddlers, shopkeepers, laborers, beggars. Thanks to economic breakdown and the mortality rate, the city’s governor never had to worry about population control.

One Friday afternoon in December, Myron Phelps looked out over the sunbaked boxes of coarse Jerusalem stone that lined ‘Akká’s streets. They had flat cement roofs, and sheets of stucco clung to their walls in varying stages of decay. To his right, the blue waters of the Mediterranean came to the foot of the stone sea wall, and, across the bay, the silhouette of a long low mountain covered the horizon. Thirty feet below his window, a group of men and women wearing patched and tattered garments gathered in the narrow street.

“It is a noteworthy gathering,” Phelps wrote. “Many of these men are blind; many more are pale, emaciated, or aged. Some are on crutches; some are so feeble that they can barely walk. Most of the women are closely veiled, but enough are uncovered to cause us well to believe that, if the veils were lifted, more pain and misery would be seen.”

“A door opens and a man comes out. He is of middle stature, strongly built. He wears flowing light-coloured robes. On his head is a light buff fez with a white cloth wound about it. He is perhaps sixty years of age. . . . He passes through the crowd, and as he goes utters words of salutation.”

“He stations himself at a narrow angle of the street and motions to the people to come towards him. They crowd up a little too insistently. He pushes them gently back and lets them pass him one by one. As they come they hold their hands extended. In each open palm he places some small coins. He knows them all. He caresses them with his hand on the face, on the shoulders, on the head. Some he stops and questions. An aged negro who hobbles up, he greets with some kindly inquiry; the old man’s broad face breaks into a sunny smile, his white teeth glistening against his ebony skin as he replies. . . . To all he says, ‘Marhabbah, marhabbah.’” (Welcome, welcome!)

“When they address him they call him ‘Master.’”

“This scene you may see almost any day of the year in the streets of ‘Akká. . . . “In the cold weather which is approaching, the poor will suffer, for, as in all cities, they are thinly clad. Some day at this season . . . you may see the poor of ‘Akká gathered at one of the shops where clothes are sold, receiving cloaks from the Master. Upon many, especially the most infirm or crippled, he himself places the garment, adjusts it with his own hands, and strokes it approvingly, as if to say, ‘There! Now you will do well.’ There are five or six hundred poor in ‘Akká, to all of whom he gives a warm garment each year.”

“Nor is it the beggars only that he remembers. Those respectable poor who cannot beg, but must suffer in silence – those whose daily labor will not support their families – to these he sends bread secretly.”

“If he hears of any one sick in the city – Moslem or Christian, or of any other sect, it matters not – he is each day at their bedside, or sends a trusty messenger. If a physician is needed, and the patient poor, he brings or sends one, and also the necessary medicine. If he finds a leaking roof or a broken window menacing health, he summons a workman, and waits himself to see the breach repaired. If any one is in trouble – if a son or a brother is thrown into prison, or he is threatened at law, or falls into any difficulty too heavy for him – it is to the Master that he straightway makes appeal for counsel or for aid. Indeed, for counsel all come to him, rich as well as poor.”

“This man who gives so freely must be rich, you think? No, far otherwise. Once his family was the wealthiest in all Persia. But this friend of the lowly, like the Galilean, has been oppressed by the great. For fifty years he and his family have been exiles and prisoners. Their property has been confiscated and wasted, and but little has been left to him. Now that he has not much he must spend little for himself that he may give more to the poor. His garments are usually of cotton, and the cheapest that can be bought. Often his friends in Persia – for this man is indeed rich in friends . . . send him costly garments. These he wears once, out of respect for the sender; then he gives them away.”

“Such is Abbas Effendi, the Master of ‘Akká.”