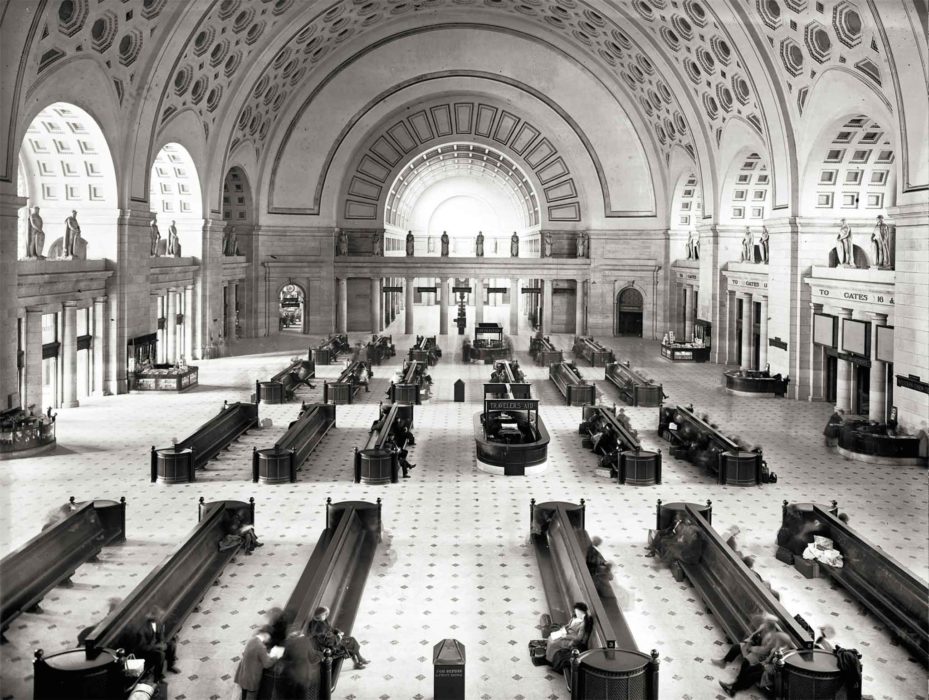

LITTLE MARZIEH KHAN BOUNCED across the pavement, passed beneath the tall marble arches, and shuffled through the glass doors of Washington’s Union Station, looking for ‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Above her a massive barrel vault, graced with octagonal coffers, crowned the cavernous Great Hall. Hundreds of little black squares dotted the marble tiled floor that unfurled at her feet. She could examine them closely because her eyes were so close to the ground. Marzieh was only four years old..

This morning — Saturday, April 20, 1912 — ‘Abdu’l-Bahá had boarded the 8 a.m. train to Washington, DC, from New York’s Pennsylvania Station. But in order to avoid the kind of brouhaha that had greeted the Cedric, he had kept his arrival time a secret. That’s why Marzieh’s parents — Florence Breed of Boston and Ali-Kuli Khan of Iran — had received a panicked telephone call at lunchtime: “Hurry! The Master is arriving at the station in half an hour!” They dropped their knives and forks, picked up the children, and ran into the street to catch a public victoria.

The Khans arrived at Union Station with five minutes to spare: the train pulled in at 1:33 p.m. Mother rushed into the flower shop and bought two bouquets. Rahim, Marzieh’s elder brother, received violets; she got red roses. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá loved flowers.

Marzieh caught her first glimpse of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá as he walked toward them along the train platform, trailed by three Persian members of his party. At the gate he stopped to greet the children, taking Rahim by the hand. “Pass along – don’t block the passage,” a guard said.

She looked up at ‘Abdu’l-Bahá as he paced along the walk beside the tracks. Atop his left shoulder, lying almost fully open, Marzieh spied a silver curl. She had curls, too. They were black and made with a curling stick. They fell to her shoulders on either side of her face, framing her olive complexion and big dark eyes.

That was the only visual image she would ever recall of that day with ‘Abdu’l-Bahá. But she would always remember the electricity that permeated the air all around him, a “feeling of something always going on.”

In front of the station two cars and a carriage awaited the party, and, as they walked back out under the arches with the others, they could see the silhouette of the Capitol building beneath the sun.

Marzieh sat on ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s lap all the way up Massachusetts Avenue. They drove around the big white library where ‘Abdu’l-Bahá was going to talk that evening. It was in a grassy park right in the middle of the road. They turned right at Dupont Circle, which was near where the President lived, and arrived a few minutes later at Mr. and Mrs. Parsons’s big house at the corner of 18th and R Streets. That’s where ‘Abdu’l-Bahá was going to stay.

We don’t know what Marzieh did for the rest of that exciting day. But ‘Abdu’l-Bahá rested, then took a carriage ride through the Mall in the late afternoon, before his speech to 600 people at the Carnegie Library. He walked along the terrace on the western side of the Capitol, and gazed out over the city as the sun slowly dropped to the horizon, shedding yellow, purple, and orange across the sky.