NO ASPECT OF SOCIAL equality threatened the sensibilities of both white and black Americans in 1912 more than the prospect of sexual union between the races. “I have three daughters,” ‘Pitchfork’ Ben Tillman declared on the floor of the US Senate in 1907, “but so help me God, I had rather find either one of them killed by a tiger or a bear and gather up her bones and bury them . . . than to have her crawl to me and tell me the horrid story that she had been robbed of the jewel of her womanhood by a black fiend.”

Racist brands of Christian theology added to the terror among whites: Charles Carroll argued that Africans “were not of the human family,” but rather the beasts that had fornicated with Cain, thereby causing sin to flood the world.

The intimate connection between social equality and sexual fear in American minds emerges in Southern responses to Booker T. Washington’s 1901 dinner engagement at the White House. “Eating at the same table,” read a letter to the editor of the Jacksonville Metropolis, “means social equality. Social equality means free right of inter-marriage, and inter-marriage means the degradation of the white race. When the white race yields social equality with the negro it has defied the laws of God, and he will sweep them from the earth.”

Race amalgamation would also bring social chaos. “All mixed races,” wrote E. H. Randle in 1910, “are inherently violent, incoherent, incapable of national government, revolutionary, and are as the downgrade of civilization.”

More forward-thinking Christian reformers, who believed in the essential unity of humanity and the danger of segregation, couldn’t bring themselves to sanction interracial unions either. Thomas Underwood Dudley, the Episcopal Bishop of Kentucky, had believed that American blacks and whites were “the descendants of one father, the redeemed children of one God, the citizens of one nation, neighbors with common interests.” He had envisioned the day when “the red man, the yellow, the white, and the black may all have ceased to exist as such, and in America be found the race combining the bloods of them all.” But he was careful to note: “it must be centuries hence.” In the meantime, “Instinct and reason, history and philosophy, science and revelation, all alike cry out against the degradation of the race by the free commingling of the tribe which is highest with that which is lowest in the scale of development.”

African Americans — whenever they didn’t share the same potent feelings — usually opposed interracial marriage on the grounds of racial pride and solidarity. The response of black leaders can best be described as conflicted. The issue carried serious consequences for their civil rights struggle, because even addressing it was certain to chase away virtually all their white supporters. Frederick Douglass married a white woman in 1884, but in his autobiography he sidestepped interracial marriage as an issue by taking the most far-fetched and ambiguous position imaginable: “If it comes at all, it will come without shock or noise or violence of any kind, and only in the fullness of time, and it will be so adjusted to surrounding conditions as hardly to be observed. I would not be understood as advocating intermarriage between the two races.”

Even W. E. B. Du Bois seemed unable to come to terms with the issue. He and other black leaders found themselves helplessly embroiled in a moral catch-22. If they supported interracial marriage they risked lynchings and racial violence by whites. But if they failed to campaign for its legality they exposed black women to sexual violence. White men had used their social power to take advantage of black women for centuries, while polite society quietly looked the other way.

When Du Bois’s editorial in The Crisis in February, 1913, appeared to argue for interracial marriage, the white female members of the NAACP’s leadership revolted. By 1920 he had changed gears: “It is not socially expedient today for such marriages to take place; the reasons are evident: where there are great differences of ideal, culture, taste and public esteem, the intermarriage of groups is unwise, because it involves too great a strain to evolve a compatible, agreeable family life and to train up proper children.”.

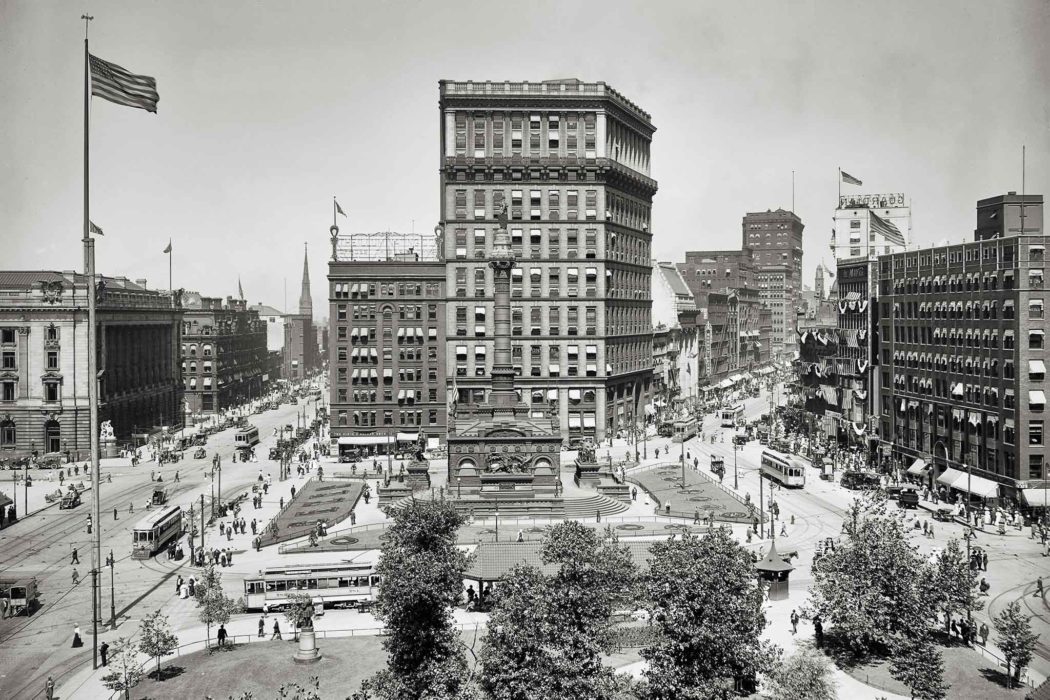

‘Abdu’l-Bahá arrived at Cleveland’s Union Station on the New York Central train from Chicago at 4:20 p.m. on May 7, 1912. During the past two weeks, Americans had learned of his battle against the ideologies of racial prejudice from major Washington newspapers and the Chicago Defender. But hardly anyone, whether black or white, had any inkling of just how far ‘Abdu’l-Bahá was willing to go.

Reporters and visitors followed him up to his rooms after his evening talk to 200 people at the Hotel Euclid. To an African-American clergyman and a group of about twenty white women sitting in a circle, he broached the most dangerous of all subjects. The Cleveland Plain Dealer, one of Ohio’s biggest newspapers, reported it unvarnished the next morning:

“Abdul Baha . . . declared last night for an amalgamation of the white and negro races by intermarriage.” What ‘Abdu’l-Bahá advocated was illegal in twenty-nine of the forty-eight states — but not in Ohio.

At Howard University in Washington, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá had turned the tables on America’s entrenched language of race by recasting racial differences as a source of beauty. In Chicago at the NAACP conference he had used rhetorical questions to uncover the absurdity of color discrimination. Tonight in Cleveland, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá took aim at the myth of mixed-race degradation.

“Perfect results follow the marriage of black and white races,” he said.

And he had evidence. A Negro woman had worked for his own family in Persia. “She married a white man,” he explained, “and her children married white men. These children are now in my household. The results of the union were beautiful. They were wonderful — perfect.”

On the issue of race, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá had employed novel arguments before, but each time he had followed them up with action. After his talk at Howard he had made a point of overturning Washington protocol by bringing a black man to the table. In Chicago, his speech at Handel Hall synchronized with a group of white delegates from forty-three cities electing a Negro to their Executive Committee.

When it came to the ultimate taboo — interracial marriage — ‘Abdu’l-Bahá wasn’t finished yet.