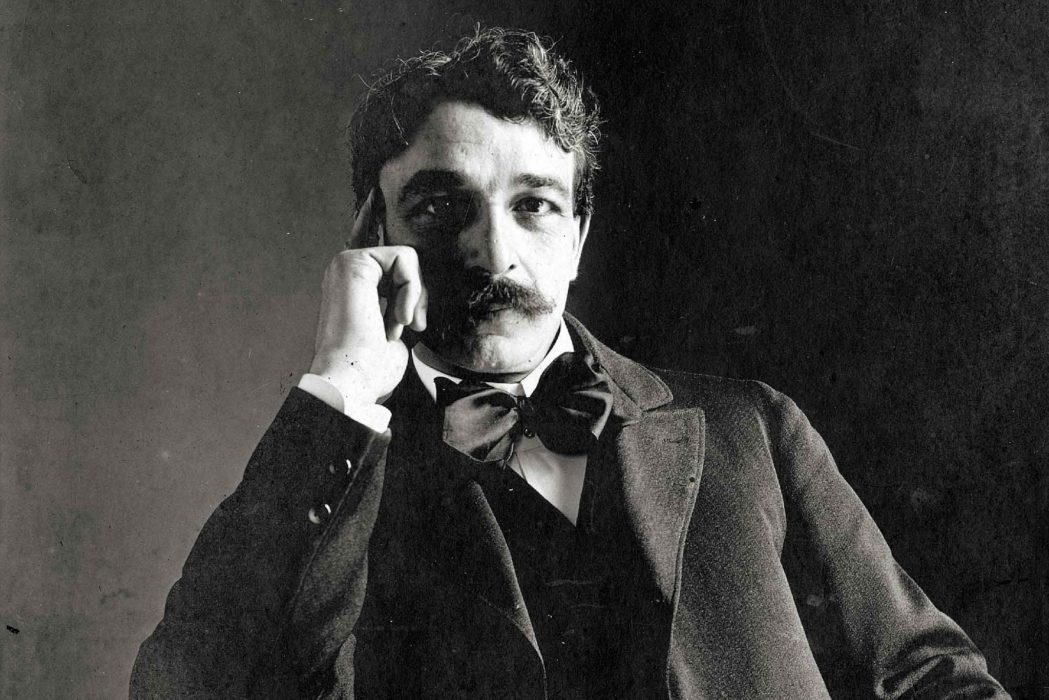

IN THE CLOSING MONTHS of 1911, Howard Colby Ives paused at a small book stall in Manhattan and looked upon the face of a man who would reorder the whole course of his life.

Ives was a Unitarian minister whose life had been a protracted, and often desperate, struggle for spiritual meaning. He was a voracious reader of weighty tomes on theology, philosophy, and social thought, but on this day he picked up the December issue of Everybody’s Magazine. On page 775, amid leaves of advertisements for Waverly electric cars and AutoStrop safety razors, he read a story about the birth of a new religion.

“My life divides itself, in retrospect, sharply in two,” Ives later wrote. The years before he met ‘Abdu’l-Bahá he defined as “forty-six years of gestation.” His autobiography, Portals to Freedom, casts aside these nearly five decades in a few short paragraphs.

The article, “The Light in the Lantern” by Ethel Stefana Stevens, who had visited ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in ‘Akká, was a dramatic account of the beginnings of the Bahá’í Faith in nineteenth century Persia. It mentioned ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s pending trip to America, and promised the reader a “first-hand, intimate study” of the Master. It was a tale filled with rousing triumphs and brutal repression, complete with striking pencil sketches of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá that captured Ives’s imagination.

“I had come to grips with the goblins of superstition masquerading as churchly creeds and had cast them out,” he said of his agnostic twenties. There were, he was convinced, “few, if any, Christians in the world, and certainly no expressions of social, economic and national life worthy of such a name.” Nevertheless, in his early thirties he decided to join the ministry.

His chosen vocation only created greater uncertainty:

“To preach once a week; duly to make my parish round of calls on elderly spinsters and the sick to whom my visits were simply what I was paid to give; never to forget the collection, for which lapse of memory my treasurer was always scolding me. . . . Did this round of living contain the germs of that ‘Truth for which man ought to die’?”

By the end of 1911, Howard Colby Ives’s spiritual quest had become a spiritual crisis. It was a period filled with “anxiety, darkness, and a vacancy of meaning.” Disappointed with his day job, he started a second “evening” church for poor men, dedicated to the principles of the Social Gospel – “a group of brothers of the spirit aiming to express their highest ideals in service to struggling humanity.” Meetings of the Brotherhood Church were held each Sunday night at the Masonic Hall in Jersey City.

Then his life took a surprising turn. A member of the Board of Trustees at the Brotherhood Church arranged an invitation for Ives to meet some Bahá’ís in New York. Ives hesitated: “Oriental cults, Eastern philosophies, and the queer, supposedly idealistic movements of which there are so many, had never appealed to me.” His mind didn’t connect this “oriental cult” with the story he had read in the magazine.

“I do not remember much of what happened,” Ives later wrote of the event. “There were readings of beautiful prayers. . . . No hymns, none of the religious trappings I had been accustomed to: but there was a spirit that attracted my heart.”

Little did Howard Colby Ives suspect that, just four months later, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá would stride up the aisle of his own Brotherhood Church, and address his congregation on the very meaning of brotherhood.