FRANK SINATRA SANG THAT he wanted to “Wake up in the city that doesn’t sleep.” He meant New York. But, on June 13, 1912, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá just wanted to sleep.

“I was tired so I slept,” he said, after resting briefly in the middle of the afternoon. It had been another busy day at his residence in Manhattan. Several prominent ministers had called to converse, drink tea, and invite him to speak at their churches. As usual, the front door had opened to visitors at 7:30 a.m. and would remain so until midnight, when ‘Abdu’l-Bahá would often start attending to his correspondence.

He frequently survived on less than three hours sleep. In fact, throughout his life, sleep had often been something of a luxury.

When Bahá’u’lláh’s family was under house arrest in Adrianople, it had been the squealing of the rats that kept them awake. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá would light bright lamps to keep the vermin away, but then the light would make it hard to sleep. Sleep was always hard won by the prisoners of the Ottoman Empire.

The family’s banishment eventually landed them in Constantinople, the empire’s capital, in 1863. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá was nineteen, and saw himself as his father’s chief protector. He rode alongside Bahá’u’lláh’s wagon on a temperamental Arab stallion, taming it with his expert horsemanship. The horse became his partner in sleep. They would often gallop across the desert wastes of Iraq, far ahead of the exiles’ caravans, and dismount. Then they would lie down together and ‘Abdu’l-Bahá would rest his head on the animal’s neck and sleep. When the party approached, the horse would awaken ‘Abdu’l-Bahá with a kick and they would resume.

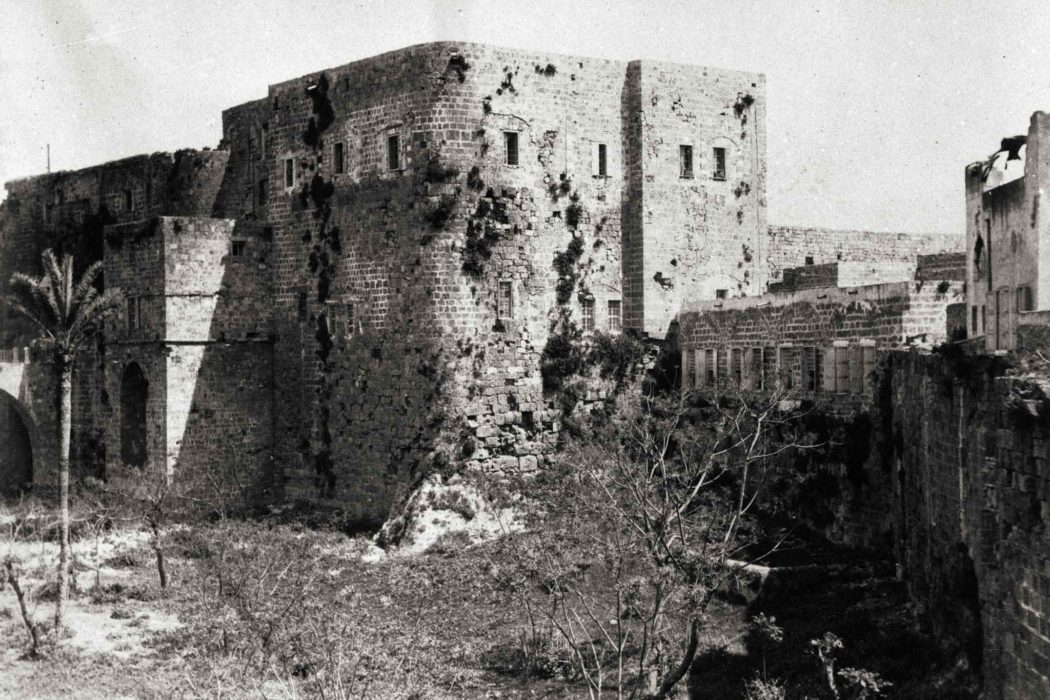

‘Abdu’l-Bahá honed his capacity to seize moments of rest under difficult circumstances. Toward the end of Bahá’u’lláh’s life, although still technically a prisoner, he had been allowed to move to a private house at Bahji, outside the prison city of ‘Akká, in 1879. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá chose to remain in the city to attend to the exiled community’s affairs, but he would walk to Bahji regularly, on foot and often in oppressive heat. If he got tired, he would simply lie on the ground and sleep, setting his head on a nearby stone.

People asked him why he didn’t travel on horseback anymore; “How can I come to my Lord riding?” he would answer. “When Christ went out he walked, and slept in the fields. Who am I, that in visiting my Lord I should go as greater than Christ?”

In New York on June 13, 1912, in the City that Never Sleeps, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá found himself with a bed, a pillow, a quilt, and a mattress with springs. So he slept.