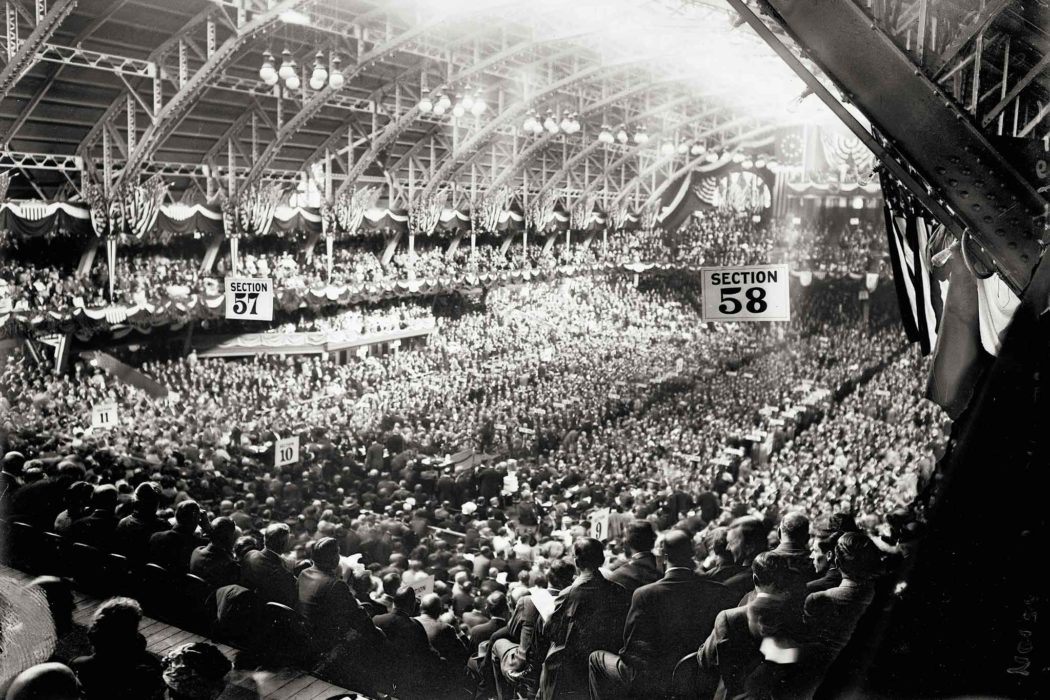

THE REPUBLICAN NATIONAL CONVENTION would be over this evening. It had begun on Tuesday, June 18, 1912, at the Chicago Coliseum on Wabash Avenue. After months of campaign speeches, accusations, and rebuttals — and twelve weeks of primary elections in sixteen states — the delegates were ready to choose either President William Howard Taft or former President Theodore Roosevelt to be the Republican Presidential nominee.

Unlike almost everyone else in the building, William Jennings Bryan didn’t have any skin in the game. He was a Democrat, and had run as the Democratic candidate for President three times, in 1896, 1900, and 1908, losing each time. This week he was here not to politick, but to report. The nation wanted his viewpoint; he was in high demand. Several daily newspapers had contracted with him for his eye on each day’s proceedings. Monday morning’s dispatch evoked the early skirmishes on the convention floor:

“The delegates as they come in are badged, tagged and buttonholed,” Bryan wrote. “The prophets are revising their lists as they learn of additions or defections and the corridors of the hotels resound with the cheers of partisans. These things are to be found in every convention, but they are here in unusual abundance.”

Although he was enjoying himself (“We are having a great time”) he could also see through the hullabaloo. “There is a liberal education in a national convention,” he told the public on Monday, “but much that one learns is not useful to him afterwards.”

On Wednesday afternoon the Roosevelt delegates struck up a spontaneous parade inside the hall, disrupting the proceedings for about forty-five minutes. “Some of the standards were carried in a parade through the aisles, with delegates young and old marching in lock step.”

In spite of all the clamor of the assembly hall, Bryan explained that picking the candidate really came down to a few backroom arguments. The Roosevelt progressives and Taft conservatives had sent competing delegations to the convention: each thought their own delegates were the rightful ones. By Monday they still disagreed on seventy-six of them. Whichever side could get their delegates seated would win a “temporary roll-call,” which would, in turn, give them a majority of the Credentials Committee. The Credentials Committee was the key because it could issue a “majority report” that would finalize the delegate count. One candidate would get a majority of the votes: it was really all about the numbers.

Roosevelt’s parade, Bryan explained, didn’t matter. “It illustrates how much noise can be turned loose in a convention without materially affecting the result,” he wrote. “Stampedes are about as much exaggerated in effect as what is known as personal popularity is in quantity. Nothing is more likely to be overestimated in politics than that peculiar quality known as personal popularity.”

Nevertheless, even though William Jennings Bryan saw through the political theatre taking place before him in Chicago, he still invested his faith in the political process. “The casual observer may be carried away by the exciting incidents of a convention,” he concluded, “but the sober citizen will see in a national convention a great human agency for the accomplishment of an important end.”

In tomorrow’s feature: The headlines from the outcome of the Republican National Convention reach ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in Montclair, New Jersey.