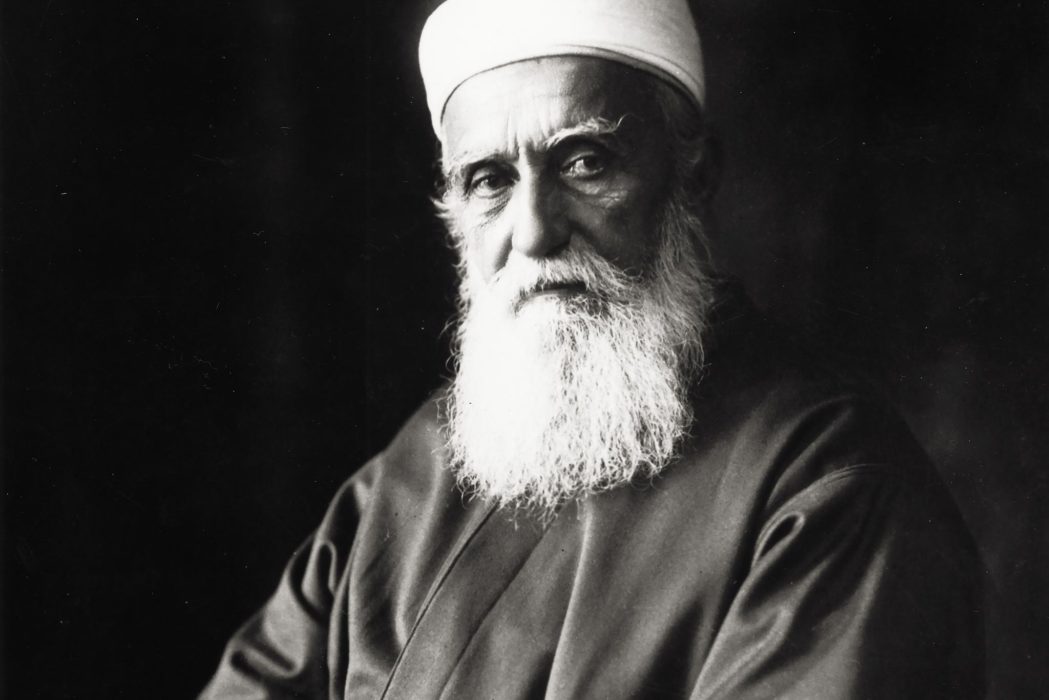

IT SEEMED THAT EVERYONE who met ‘Abdu’l-Bahá had a different opinion about who this man really was. A newspaper article covering his arrival in America introduced him as “ABDUL BAHA ABBAS, HEAD OF NEWEST RELIGION . . . .” He was called a philosopher, a saint, “His Holiness,” and every possible variation of prophet — “Prophet of Peace,” “Prophet of the East,” “The Great Persian Prophet” — in spite of him having announced, “I am not a prophet,” as he stepped onto American soil.

In Washington, DC, on April 27, 1912, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá had breakfast with Lee McClung, Treasurer of the United States. McClung commented: “I felt as though I was in the presence of one of the great old Prophets: Elijah, Isaiah, Moses. No it was more than that! Christ . . . no, now I have it! He seemed to me my Divine Father.”

Many Americans, in fact, had decided that ‘Abdu’l-Bahá was the return of Christ, something he emphatically denied. Some clung to the belief for years.

Others, who were less concerned with names and titles, had trouble pinning him down. Kate Carew, the New-York Tribune’s celebrity interviewer, described ‘Abdu’l-Bahá as both wonderfully childlike and venerably wise. Howard Colby Ives, a Unitarian minister from New Jersey, wrote that his time with ‘Abdu’l-Bahá left him simultaneously in a state of peace and incredible turmoil.

Yet virtually everyone agreed on ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s compelling presence, and the power of his words. As he traveled across America presenting the teachings of his father, Bahá’u’lláh, he drew audiences by the thousands.

On June 2, 1912, at the Church of the Ascension in New York, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá was asked a question that got to the heart of how he saw himself. A woman asked: “What relation do you sustain to the founder of your belief? Are you his successor in the same manner as the Pope of Rome?”

‘Abdu’l-Bahá was neither a priest, nor an ecclesiastical leader, nor a figure to be worshipped. His father, Bahá’u’lláh, in his Will and Testament, gave ‘Abdu’l-Bahá sole authority to interpret his teachings. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá explained what this meant to an audience in America on December 2, 1912: “To ensure unity and agreement [Bahá’u’lláh] has entered into a Covenant with all the people of the world, including the interpreter and explainer of His teachings, so that no one may interpret or explain the religion of God according to his own view or opinion and thus create a sect founded upon his individual understanding . . . .”

Bahá’u’lláh appointed ‘Abdu’l-Bahá to ensure that his religion would never splinter into competing sects, as had happened to every other major faith. His name, literally, means “servant of Bahá.”

This concept took some time for the American followers of Bahá’u’lláh to grasp. Years before, in a letter to an American who was confused over whether he was the return of Christ, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá had stated exactly how he saw himself: “My name is ‘Abdu’l-Bahá. My qualification is ‘Abdu’l-Bahá. My reality is ‘Abdu’l-Bahá. No name, no title, no mention, no commendation have I, nor will ever have, except ‘Abdu’l-Bahá.”