‘ABDU’L-BAHÁ WALKED WITH Agnes Parsons from Day-Spring up the hill towards Tiny May where he sat on the grass near some trees. They spoke about Agnes’s eldest son, Royall. Earlier, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá had met Royall, but the boy had bolted. “He flew away from me,” ‘Abdu’l-Bahá told her, “but I was very pleased with him.” Agnes wondered how he could be pleased with her son when he had acted so badly. Royall was mentally handicapped.

Across the ocean — at exactly the same time — a group of men were talking about what should be done with people like Royall. It was the First International Eugenics Congress at the University of London, which was being held between July 24 and July 30, 1912.

Charles Davenport, a member of the American Breeders Association, was a leader in the study and application of eugenics in America. “Forget unessentials like skin color,” he said. “Focus attention on socially important defects. Then by sterilization or segregation, prevent the reproduction of the socially inadequate. Thus will the mentally incompetent strains be eliminated.. . .”

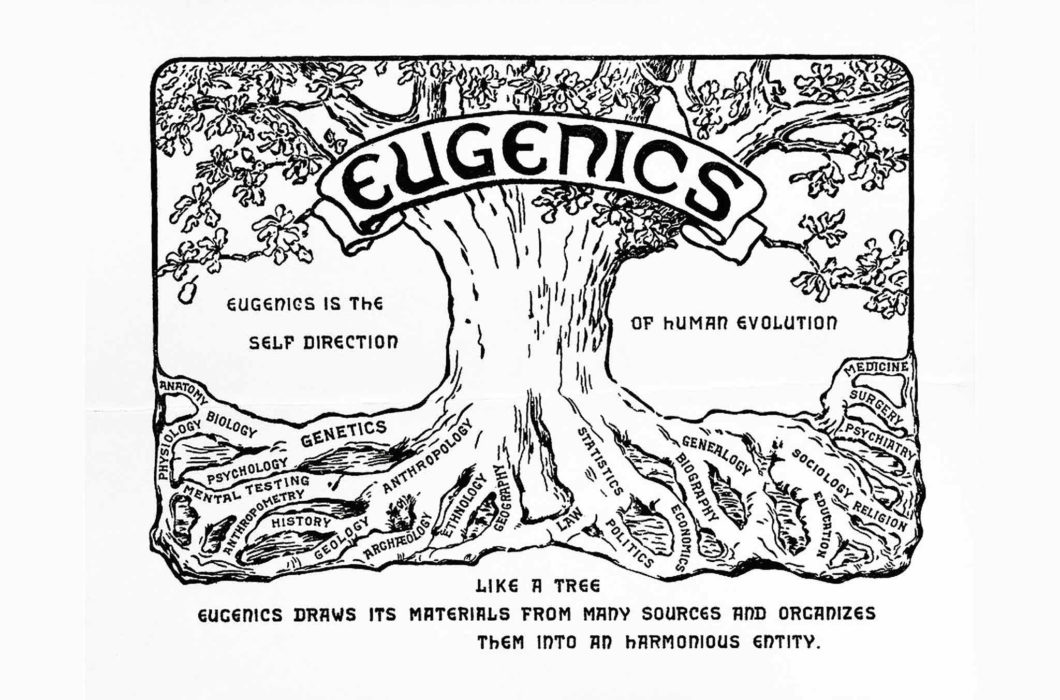

Eugenics was the science of how to create a pure society by selective breeding. Charles Darwin’s son, Leonard, had captured the aspirations of many when he opened the Congress and asked: “May we not hope that the twentieth century will be known in the future as the century when the eugenic ideal was accepted as part of the creed of civilisation?”

By 1912 eugenic ideals had seeped into every facet of life, and were favored by many reformers, including scientists like Alexander Graham Bell; businessmen like Vernon Kellogg, the cereal magnate; politicians like Theodore Roosevelt; and playwrights like George Bernard Shaw. Even those whose motive was to alleviate the conditions of the poor, like Margaret Sanger, succumbed to its powerful voice. Eugenicists were especially concerned with the African, the immigrant, the mentally ill, and those they described as feeble-minded. “May we not hope,” Willett M. Hays wrote, “to advance greatly the average of efficiency, to practically lop off the defective classes below, and also increase the number of the efficient at the top?”

‘Abdu’l-Bahá had a completely different opinion about what the response to Hays’s so-called “defective classes” must be:

“Even though we find a defective branch or leaf upon this tree of humanity or an imperfect blossom,” he told Reverend Harvey’s congregation in Brooklyn last week, “it, nevertheless, belongs to this tree and not to another. Therefore, it is our duty to protect and cultivate this tree until it reaches perfection.”

Pruning, he argued, was not a strategy acceptable to humanity: “If we examine its fruit and find it imperfect, we must strive to make it perfect. There are souls in the human world who are ignorant; we must make them knowing. Some growing upon the tree are weak and ailing; we must assist them toward health and recovery.”

“If they are as infants in development, we must minister to them until they attain maturity,” ‘Abdu’l-Bahá said. “We should never detest and shun them as objectionable and unworthy. We must treat them with honor, respect and kindness; for God has created them.”

As Agnes and ‘Abdu’l-Bahá sat talking about Royall, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá explained why he had been pleased with her son. “He judged from what was within, not by externals,” Agnes heard him say, “that such people as Royall are pure, clear sighted, inspirational, even prophetic.” He assured Agnes that all are in God’s hands and that “there is a wisdom in this experience.”