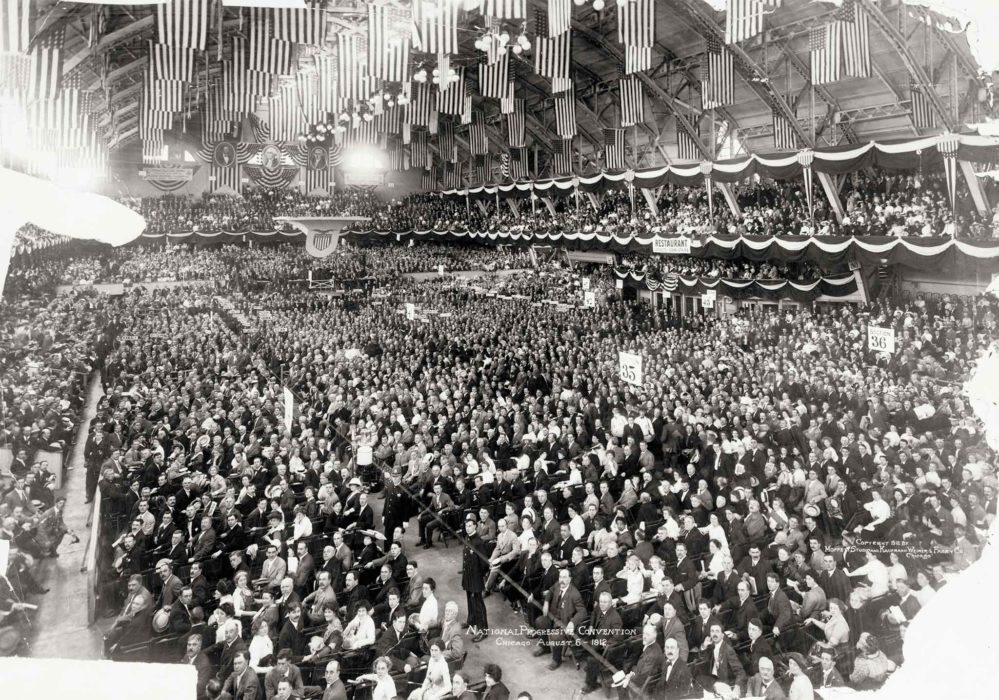

THE MOMENT THEODORE ROOSEVELT appeared on stage, a sea of red bandanas erupted from the ten thousand people who filled the Chicago Coliseum. It was one o’clock in the afternoon on Sunday, August 6, 1912. TR stood smiling, waving, and shaking hands for fifty-eight minutes before the demonstrations, the songs, and the cheering died down enough for him to finally step forward and speak.

The National Progressive Party Convention was the fourth convention of this unusual election year. The socialists had named their presidential candidate in May, the Republicans in June, and the Democrats at the beginning of July. A few hours after losing the Republican nomination to President Taft on Saturday, June 22, Roosevelt and his supporters had met in Chicago’s Orchestra Hall and started a new political party.

“The victory shall be ours,” he told them. “We fight in honorable fashion for the good of mankind; fearless for the future; unheeding of our individual fates; with unflinching hearts and undimmed eyes; we stand at Armageddon, and we battle for the Lord!”

“Never before had Roosevelt used such evangelical language, or dared to present himself as a holy warrior,” Edmund Morris writes in his 2010 Pulitzer Prize-winning biography of the Colonel. “Intentionally or not, he invested progressivism with a divine aura.”

More than a month later, as the Progressive Party convened in Chicago, the transcendent glow remained. “It was not a convention at all,” the New York Times deduced on August 6. “It was an assemblage of religious enthusiasts. . . . It was a Methodist camp meeting done over into political terms.” The New York delegation marched into the Coliseum singing “Onward, Christian Soldiers”; “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” rang out repeatedly.

Roosevelt’s speech, entitled “A Confession of Faith,” lasted for two hours, partly because the Coliseum interrupted him with applause 145 times. Jane Addams of Hull House sat in the front row. The next day, August 7, she became the first woman to second the nomination of a presidential candidate. “I have been fighting for progressive principles for thirty years,” she said as she left the stage. “This is the biggest day in my life.”

But in spite of the prolonged cheers, the red swarm of waving flags, and the militant hymns, the fanfare in Chicago on this first weekend in August belied the mundane reality at the heart of the 1912 election. Months before any American would have a chance to cast a vote for President, the outcome had already been determined.

“My public career will end next election day,” Theodore Roosevelt had admitted to a visitor on July 3. The previous afternoon, on July 2 in Baltimore, the Democratic Party had nominated Woodrow Wilson. Wilson’s record of progressive reform as Governor of New Jersey had brought him to national prominence. Roosevelt, by splitting the Republican vote, had handed the pen to the Democrats, and they, by nominating the progressive Wilson, had sealed the deal.

“In writing the history of a presidential election,” scholar Lewis L. Gould explains, “one can easily convey the impression that a majority of the American people felt a passionate interest in the outcome.” But fewer Americans cared in 1912. “To some degree,” he argues, “Americans were now more spectators than participants in the operation of this presidential race.”

After 1912, Gould writes, “Americans would be less politically mobilized, participation would recede, and the nature of government itself would become more bureaucratic and removed from the people.” Like so many of the legacies of the 1912 presidential election, the decline of voter participation in national elections continues to this day.