LAST WEEK, AS WE reached the midpoint of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s journey, someone asked me what aspect of the story had surprised me the most. What immediately came to mind was ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s engagement with the issue of race. Living on this side of the Civil Rights era, it is perhaps impossible for any of us to truly understand the racial milieu of 1912, and to grasp how singular it was for a man from the Middle East to arrive on American shores and begin to enact change.

On further reflection, I realize that I have been continually surprised at how modern — or even American — ‘Abdu’l-Bahá was. He had been in exile or prison for almost sixty of his sixty-seven years, yet here he was strolling through the streets of New York, fully in sync with the hectic pace, and often improvised character, of American life. This unlikely convergence is perhaps best exemplified in his interview with Kate Carew.

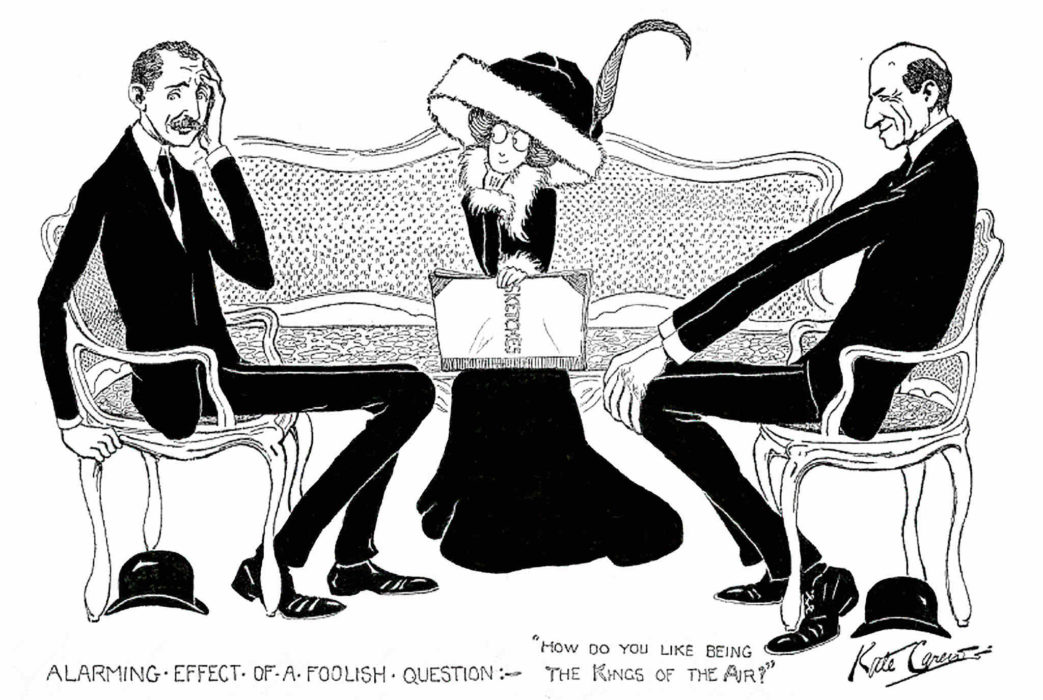

Carew was an urbanite, a hard core New Yorker. In 1890 she leveraged her artistic skill and gargantuan personality to land a job at Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World. She would sketch the rich and famous, and interview them at the same time. First up was Mark Twain who flatly refused to be interviewed. He had a contract with a publisher that granted them rights to everything he said. But Kate took him to breakfast with her sketchbook and coaxed out an interview that launched her career. In no time, she crafted herself into a brand, complete with a pseudonym (her real name was Mary Williams), a closet full of trademark flamboyant hats, and a fearless wit.

She called Picasso “the forerunner of heaven alone knows what in art.” The Wright brothers feared her, but, once things got going, they couldn’t stop giggling. She asked if women passengers were hard to manage. “Much better than men,” they said. She added: “And yet they deny us the suffrage.” When interviewing the controversial black boxer Jack Johnson, she asked: “Are you anxious to undermine the supremacy of the Caucasian race?” Johnson rolled his eyes and played along.

Carew went on to interview entertainers such as Ethel Barrymore and Sarah Bernhardt, politicians including Winston Churchill and Theodore Roosevelt, and tycoons such as J. Pierpont Morgan. She was quicker on her feet than any of them: a few even walked out.

So what would one expect when she interviewed ‘Abdu’l-Bahá?

Her story began in typical fashion. “I felt all sorts of mystic possibilities awaited me the other side of the door,” she wrote. “I stripped my mind of all its worldly debris . . . I closed my eyes. I attained the holy calm.” One might expect things to go downhill from there; that Carew might presume ‘Abdu’l-Bahá a charlatan, or that he would find her frivolous or rude.

But within the hour, the two of them were strolling hand-in-hand through the lobby of the Hotel Ansonia, en route to the Bowery Mission. Carew took the time to carefully convey to her readers ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s interactions with the homeless men there. She was genuinely surprised as she witnessed him distribute money to the destitute, convinced “of the absolute sincerity of the man.”

“What you don’t expect!” she wrote.

The more I think through the events of that evening, the more remarkable I find them. And I tip my hat to you, Ms. Kate Carew.