This is the second in a two-part feature on the life of Sarah J. Farmer. Read Part One here: The Battles of Sarah J. Farmer

SARAH J. FARMER SAILED FROM New York aboard the SS Fürst Bismarck on January 3, 1900, accompanied by her best friend, Maria P. Wilson, bound for Egypt and a cruise up the Nile. They met two other friends on board who, she soon found out, were keeping their destination a secret. They were traveling from Egypt to meet ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in the Ottoman penal colony of ‘Akká. Sarah Farmer cabled ahead for permission to join them. When she returned to America on November 1, 1900, she returned with renewed determination, and with a new religion.

More than ten thousand pages of source material trace the life of Sarah J. Farmer. It is impossible to summarize here even the major events of her last sixteen years. How her intellectual battle with Lewis Janes reached a climax, then ended (he died); how she averted Green Acre’s financial collapse; how fire destroyed her personal wealth when her home burned to the ground; how the New England press suddenly turned against her; how she was attacked by the special interest groups who feared that her embracing ‘Abdu’l-Bahá might curtail their freedom at Green Acre; how emotional exhaustion from the resulting turmoil finally felled her; and how she was eventually imprisoned in a private sanitarium for five years on the presumption that she had lost her mind, under the control of a man who drugged his patients to oblivion, censored her mail, prevented family from seeing her, and kept her locked up behind bars in a second-story room on Middle Street in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, while battles for control over her person and her property raged in the courts and in the popular press — all of these things we must leave aside for another time.

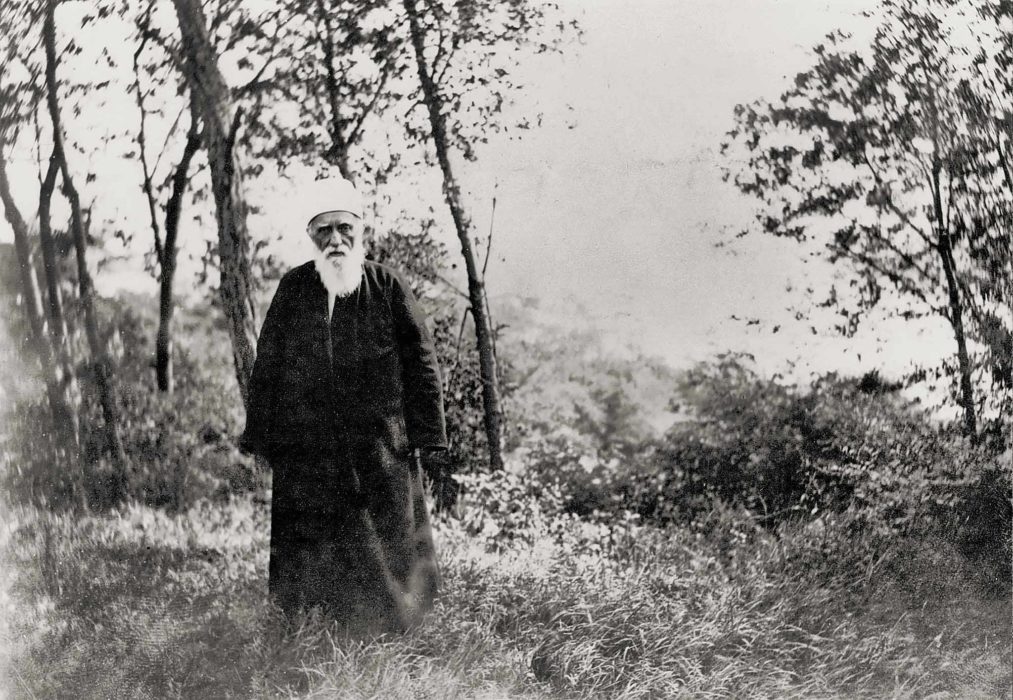

It was that doctor, Edward S. Cowles, who sat in the front seat of the automobile on Tuesday, August 20, 1912, keeping watch lest the crowd at Green Acre swarm the car and remove Miss Farmer from his control. Although she had been away for three years, he didn’t even let her set foot on Green Acre’s grounds. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá got into the car and it whisked them off to Sunset Hill, a high plateau on the other side of Eliot that Miss Farmer had named Monsalvat after the sacred mountain in Wagner’s Parsifal where they kept the Holy Grail. Here she had planned to build a university and a second Bahá’í House of Worship, like the one whose cornerstone ‘Abdu’l-Bahá had laid near Chicago in May.

“When we were almost at the top of the hill,” an eyewitness on that day reported, “‘Abdu’l-Bahá took Miss Farmer’s hands in his and said very loudly, ‘This is hallowed ground made so by your vision and sacrifice.’”

It was important, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá said, that Sarah Farmer visualize the great university her efforts had made possible. He told Miss Farmer that the university would be built, the eyewitness said; he extended his arms to indicate that it would cover the whole plateau. Then he pointed to a spot where he said the House of Worship would eventually be raised.

Finally, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá turned again to Miss Farmer: “You will be revered above all American women one fine day,” he told her.

In his 2005 book, Restless Souls: The Making of American Spirituality, historian Leigh Eric Schmidt names Sarah J. Farmer as one of the great religious innovators of America’s nineteenth century, alongside Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau. For sixteen years, between 1894 and 1909, she shepherded the parliament of religions at Green Acre. In the end she suffered the price of her choices, castigated by Green Acre’s advocates of unencumbered liberty for her embrace of a single path which, she believed, was the very definition of freedom.

In this way, Sarah Farmer is emblematic of one of the core dilemmas in America’s religious life, which even the philosopher William James wrestled with. “The struggle at the heart of Farmer’s spiritual journey,” Schmidt writes, “and James’s religious psychology — the tension between autonomy and self-surrender — has hardly disappeared from America’s contemporary seeker culture.”

What has changed is America’s willingness to accept a woman’s autonomy to make her own decisions.