‘ABDU’L-BAHÁ WAS STEPPING INTO the automobile when he noticed Fred Mortensen standing in the crowd that had gathered at Green Acre to bid him goodbye. Just two days earlier, Mr. Fred Mortensen had arrived at the conference center in Eliot, Maine, after having traveled 1,600 miles as a stowaway on the rails. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá asked Fred to get into the car. The former convict would be his personal guest for the next week.

At 1 p.m. they arrived in Malden, Massachusetts, the next stop on ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s journey in America. He was staying at the home of Maria Wilson, who, twelve years earlier, had sailed with Sarah J. Farmer, her best friend, to meet ‘Abdu’l-Bahá while he was still a prisoner. At the time, he had told Miss Wilson: “When I come to America I will visit you.” On August 23, 1912, he made good on that promise.

On ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s third evening in Malden, he made the ten-mile trip to nearby Boston, to deliver a talk to the New Thought Forum. To ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s surprise, the president of the society announced that he would speak on the subject of “Captivating the Souls.” ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, more than a little adept at improvisation, complied.

“It is easy to bring human bodies under control,” he began. “In former centuries kings and rulers have absolutely dominated millions of men. . . . If they desired to send men to the field of battle, none could oppose their authority; and if they decreed their kingdoms should enjoy the bliss and serenity of immunity from war, this condition prevailed.” The point, he said, is “that to gain control over physical bodies is an extremely easy matter, but to bring spirits within the bonds of serenity is a most arduous undertaking.”

‘Abdu’l-Bahá argued that captivating the souls of men is something that can only be achieved by the power of the Holy Spirit. He noted that “Christ was capable of leading spirits into that abode of serenity.” In this age, he added, “Bahá’u’lláh has appeared and so resuscitated spirits that they have manifested powers more than human.”

It was a subject that ‘Abdu’l-Bahá returned to often during his time in America: the authority of divine teachers — such as Moses, Krishna, Jesus, Muhammad, Bahá’u’lláh — and the imperative for their teachings to be renewed in every age.

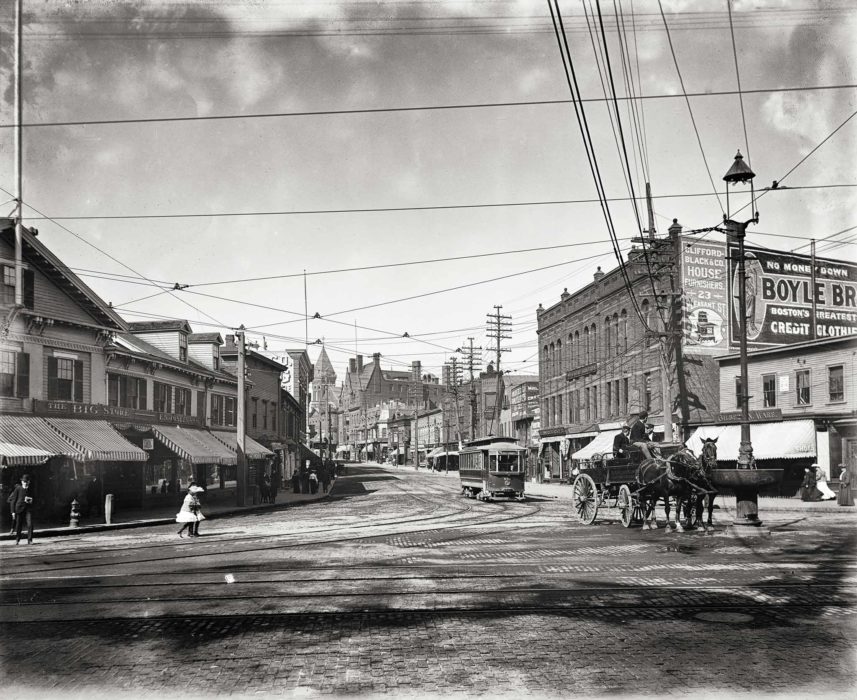

‘Abdu’l-Bahá drew some analogies to make his point about the need for the reformation of civilization. He asked: “Are the laws of past ages applicable to present human conditions?” He added: “If modes of transportation had not been reformed, the teeming millions now upon the earth would die of starvation . . . How could great cities such as New York and London subsist if dependent upon ancient means of conveyance?”

Why, indeed, was it, that modern people would never confine society within the bounds of ancient technology, but seemed content with spiritual teachings that were thousands of years old?

“In the unmistakable and universal reformation we are witnessing,” he asked them, “when outer conditions of humanity are receiving such impetus, when human life is assuming a new aspect, when sciences are stimulated afresh, inventions and discoveries increasing, civic laws undergoing change and moralities evidencing uplift and betterment, is it possible that spiritual impulses and influences should not be renewed and reformed?”