THE PROGRESSIVE ERA WAS not a rewarding time to be a working woman. While the wages of men were low, women’s pay was drastically lower. The number of females employed − typically in factories or as domestic servants − was rapidly increasing. Emma Goldman, a leading voice in the Socialist movement, wrote in 1910: “Nowhere is woman treated according to the merit of her work, but rather as a sex.”

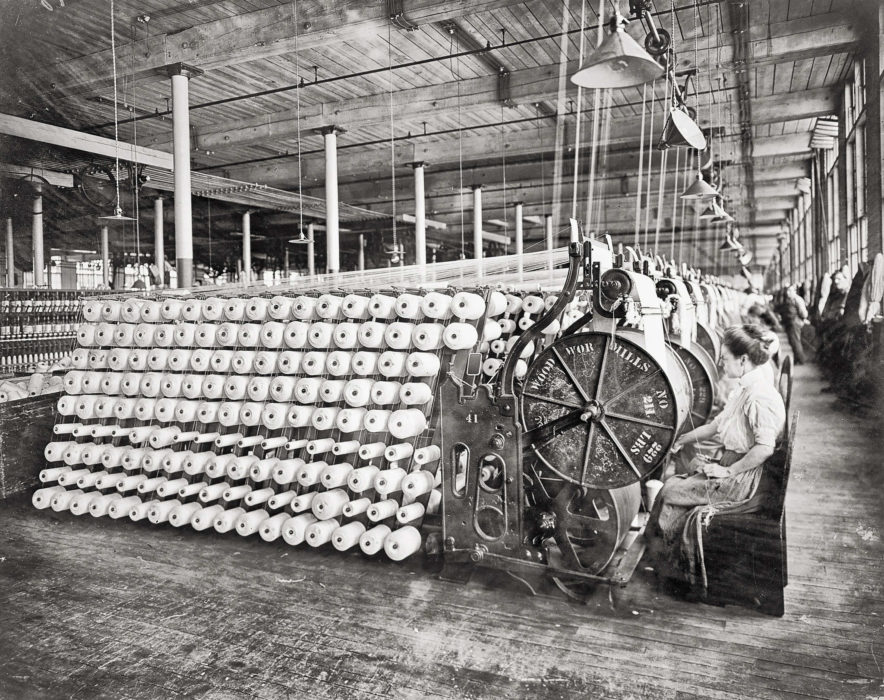

Reverend George L. Perin, a pastor serving inner city Boston, decided to lend a helping hand. He was appalled at the housing that single, working women in Boston were compelled to live in. Through a tireless fundraising effort, Perin managed to buy an unoccupied hotel in Boston’s South End. His goal was to “furnish for girls living away from home a dwelling place which is morally safe, as well as comfortable and sanitary, and to give them food that is both palatable and wholesome.” The New York Times called Franklin Square House “the largest hotel for young working women and girl students in the world.”

‘Abdu’l-Bahá visited Franklin Square House on the evening of August 26, 1912. He had been invited by its superintendent to give a talk to the nearly six hundred women that called the vine-covered, red brick building home. He began by confirming the equality of women and men. “[E]ach is the complement of the other in the divine creative plan.” ‘Abdu’l-Bahá noted that God distinguishes a person’s “purity and righteousness” in “deeds and actions,” and not their gender. He acknowledged the history of the subordination of women, attributing it to a lack of equal access to education.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá then offered a series of historical examples of women with “superlative capacity and determination,” who have been “peers of man in intellect and equally courageous.” They included Zenobia, Queen of the Palmyrene Empire, who “manifested the highest degree of capability in the administration of public affairs.” He added to the list Cleopatra, Catherine, wife of Peter the Great, and Queen Victoria, whom he noted was “superior to all the kings of Europe in ability, justness and equitable administration.”

The audience at Franklin Square House was given some practical advice. Women, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá told them, “must become proficient in the arts and sciences and prove by her accomplishments that her abilities and powers have merely been latent.” He noted:

“Woman must especially devote her energies and abilities toward the industrial and agricultural sciences, seeking to assist mankind in that which is most needful.”

‘Abdu’l-Bahá ended by addressing certain militant aspects of the women’s movement. He had met Emmeline Pankhurst, the leading British suffragist, who had resorted to aggression in order to call attention to the disenfranchisement of women. “Demonstrations of force, such as are now taking place in England,” he said, “are neither becoming nor effective in the cause of womanhood and equality.”

‘Abdu’l-Bahá had great hope that women would champion the peace movement, adding that women’s “efficiency in the establishment of universal peace,” would be “real evidence of woman’s superiority.”