‘ABDU’L-BAHÁ HAD BEEN warned about Montreal. “The majority of the inhabitants are Catholics,” he had been told, who “are in the utmost fanaticism,” covered by “impenetrable clouds of superstitions. . . .” Percy Woodcock, a Canadian who had traveled with ‘Abdu’l-Bahá to North America aboard the SS Cedric, had advised him in these terms against traveling to Montreal. Yet the concerted response of the Montreal press to ‘Abdu’l-Bahá during his stay in Canada’s largest city proved Percy Woodcock wrong.

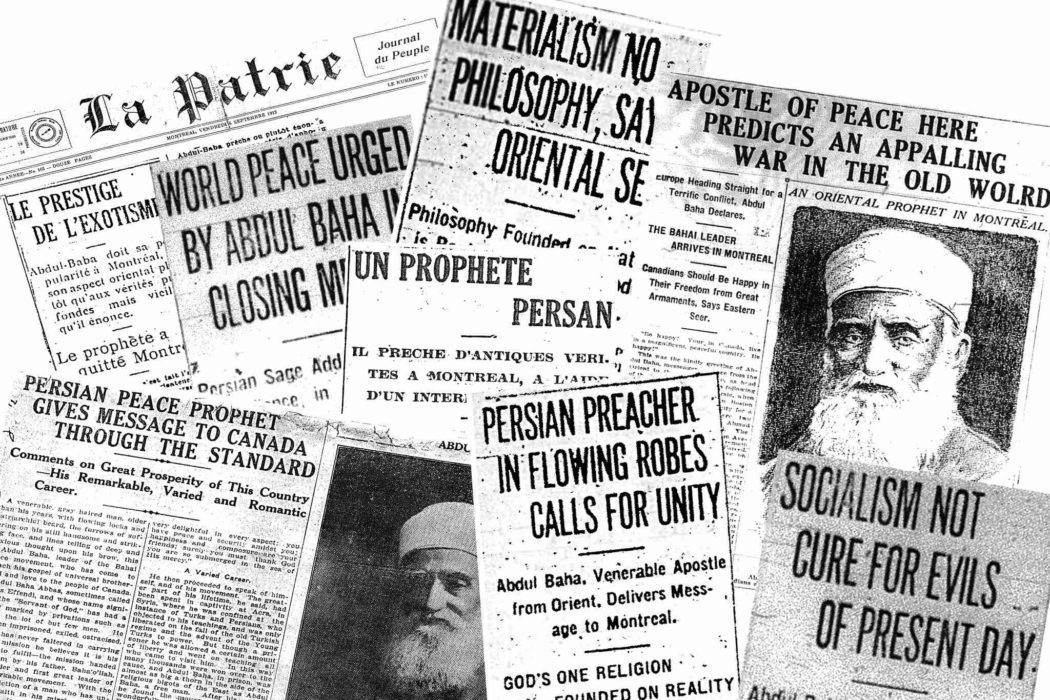

Montreal’s newspaper industry was highly competitive by 1912. At least fourteen newspapers, in both English and French, were published daily. Another fourteen weekly magazines, which focused on smaller, special interest groups within Montreal, provided the city’s inhabitants with plenty to read. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá visited Montreal during Labor Day and the visit of Prime Minister Robert Borden. Still, as Will C. van den Hoonaard recorded in his book, The Origins of the Baha’i Community of Canada, 1898-1948, twenty-five English language articles, and nine French language articles were published, a substantial number for a nine-day stay.

It wasn’t only the quantity of the articles that distinguished them, but their content as well. The English language publications of Montreal lacked the sensationalism that characterized several major American newspapers of the time. Literacy rates in America had rapidly increased, meaning that newspapers no longer had to rely on a small, educated readership for revenue. They began to sell the masses stories of adultery and crime, often told in hyperbolic, charged language and intentionally controversial. This became known as the Yellow Press.

It was in this climate that journalists were challenged to write about ‘Abdu’l-Bahá. On June 30, 1912, the New York Times published the article “Prophet’s Dash For Train,” about how ‘Abdu’l-Bahá nearly missed his train at Lackawanna Station in Montclair, NJ. It was dramatic. Nixola Greeley-Smith wrote a colorful article for Pulitzer’s New York World: “Of course nobody could be named Baha without having a beard,” she joked, admitting that she had tried to interrupt ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s talk “in the interest of those who seek lighter reading,” and was consequently “squelched.” One headline simply reads, in a reductive pun, “Hopes to Convert U.S.”

Canadian newspapers were delayed in taking on the methods of the Yellow Press. In the days before ‘Abdu’l-Bahá arrived in the city, detailed and accurate articles about his life, the Bahá’í faith, and his position in it were published. The Montreal Daily Star printed an article on August 24, 1912, six days before his arrival, and got most of its facts right. Of the religion it wrote: “It has no clergy and no ritual. It is not a cult. . .” “The one point insisted upon,” read the article, “is that the fundamentals of spiritual teaching shall be universally admitted and practically applied to the affairs of daily life and in the social, business and political life of nations.”

When ‘Abdu’l-Bahá did arrive, the content of his talks, rather than his identity as an Easterner, was the main focus of all the articles. The Daily Star published an account of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s talk at Coronation Hall. Bahá’u’lláh’s vision of an economic system based on mutual support and cooperation, but far from the oppressive rigidity of socialism, was described in full detail. Canadian newspapers called ‘Abdu’l-Bahá an “Oriental Seer,” a “Persian Preacher,” and an “Eastern Sage,” but rarely a prophet.

The French press coverage was of a different tone. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s talks had to be translated into French to be published. This could be one reason why they focused more on the impression ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s appearance made on them than on the content of his speeches. One article titled “Le Prestige de l’Exotisme,” (The Prestige of Exotic Things), published in La Patrie, according to van den Hoonaard, “attributed ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s success to the fact that he was an oriental, rather than to the ‘deep, but old truths’ he set forth.” Le Canada focused on ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s economic teachings, summing them up as an “admixture of socialism and Christianity.” The most biting article was published in Le Nationaliste. “Caliban [the writer] explained how one must have an ‘unusual’ name like ‘Abdu’l-Bahá,” van den Hoonaard wrote, “not an ordinary one, before he can call himself a ‘prophet.’”

“Many souls warned me not to travel to Montreal,” ‘Abdu’l-Bahá wrote several years after his journey. “But these stories did not have any effect on the resolution of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá. [He] turned his face toward Montreal. When he entered that city he observed all the doors open, he found the hearts in the utmost receptivity…”