“I CONSECRATED MY LIFE to making Canada a nation,” Sir Wilfrid Laurier, Canada’s former Prime Minister, said yesterday — Sunday, September 8, 1912 — in Marieville, Quebec. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá might have seen the news story on the front page of the Toronto Globe late this afternoon — Monday, September 9 — while he paced the platform of Toronto’s Union Station after a dusty seven-hour train ride from Montreal.

Last night in Montreal was a night to remember. The new Prime Minister, Robert Borden, whose Conservative Party had defeated Laurier’s Liberals in last autumn’s election by opposing Laurier’s free trade agreement with the United States, disembarked from the steamer Lady Grey at Montreal’s Victoria Pier at about 8 p.m. He had just come from Europe, where he had joined other leaders from King George V’s empire in renewing Britain’s pledge to the Entente Cordiale with France. Flags and bunting lined the streets, marching bands played, and thousands of citizens gathered and cheered. Hundreds of automobiles clogged the parade route, as if trying to prove how eagerly the new transport revolution was sweeping the city. A mile-long procession accompanied the Prime Minister to the Windsor Hotel, where ‘Abdu’l-Bahá also happened to be staying on his final night in Montreal.

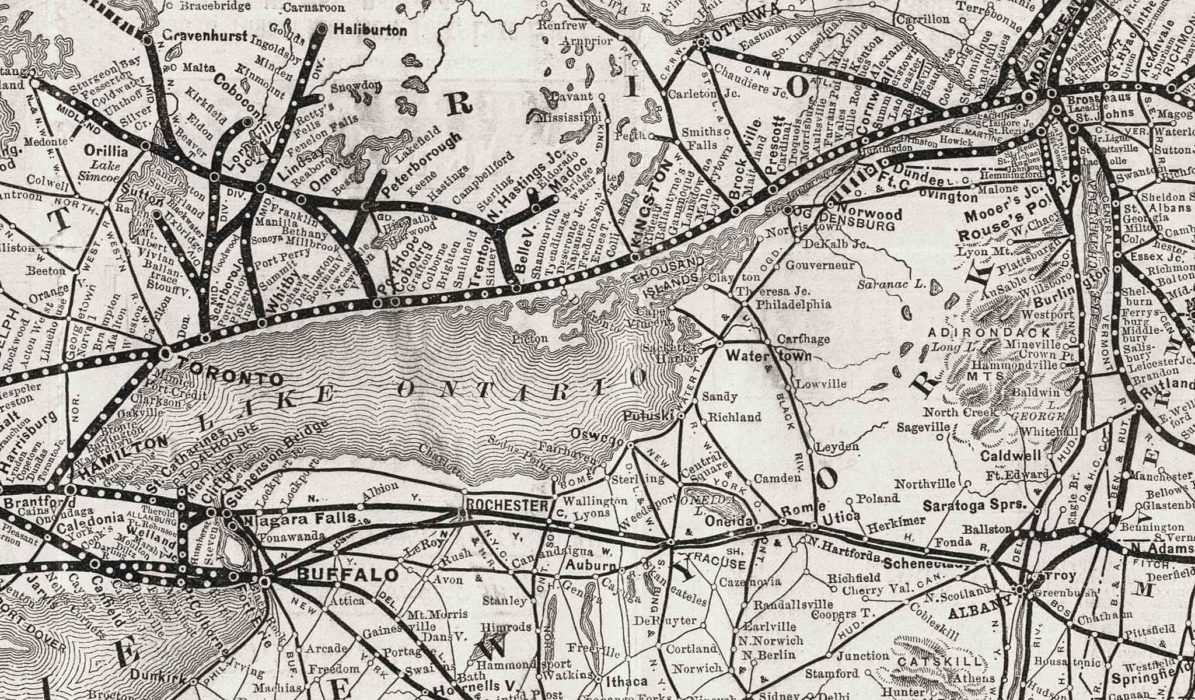

‘Abdu’l-Bahá left Montreal an hour ahead of Prime Minister Borden this morning, on a 9 a.m. train bound for Buffalo. It stopped in the town of Brockville, near the Thousand Islands, at about 10:30. It passed Kingston, and then Belleville at 1:47 p.m., from where the Great Peacemaker, Deganawidah, set out across Lake Ontario in a canoe hewn from stone to forge the Iroquois Confederacy among six warring nations in present-day New York state. Near Oshawa, at about 3:30 p.m., a four-year-old Mohawk boy, Jimmy Loft, saw ‘Abdu’l-Bahá wave to him from a window of the passing train.

They pulled into Toronto’s Union Station at 4:30 p.m. The station’s 200-foot-long south platform, where ‘Abdu’l-Bahá walked for a while, was open to the waterfront. The front page of The Globe announced that construction on the new Union Station would not begin in 1912; in fact, the building wouldn’t open for another fifteen years. The final leg of the journey to Buffalo began when the locomotive of the Toronto, Hamilton and Buffalo Railway (TH&B) puffed out of Union Station at 6:05. Then the tracks swung south through cities with climbing skylines that would soon comprise the bulk of Canada’s industrial and financial strength.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá entered the city limits of Hamilton, Ontario, at the westernmost end of Lake Ontario, not long after 7 p.m. As the train crossed the narrow strip of land that skirted the western edge of Burlington Bay, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá could see the last dull grey shimmer of evening light reflected from the waters of Cootes Paradise, a rich wetland on his right. A few minutes later the TH&B train pulled out of a tunnel downtown beneath Hunter Street, stopped traffic as it crossed Park and MacNab Streets, and came to rest for a few minutes beside the graceful Norman arches of a turreted, gabled, gingerbread castle of a passenger station, cased in natural stone and red brick at the corner of Hunter and James.

From there the train would head southeast along the TH&B rail line, hoist itself up the Niagara Escarpment on steel trestles between Stoney Creek and Vinemount, achieve Welland, and finally cross the international border at the Niagara River to arrive, after a fourteen-hour trek, in Buffalo, New York, at about 11 p.m.