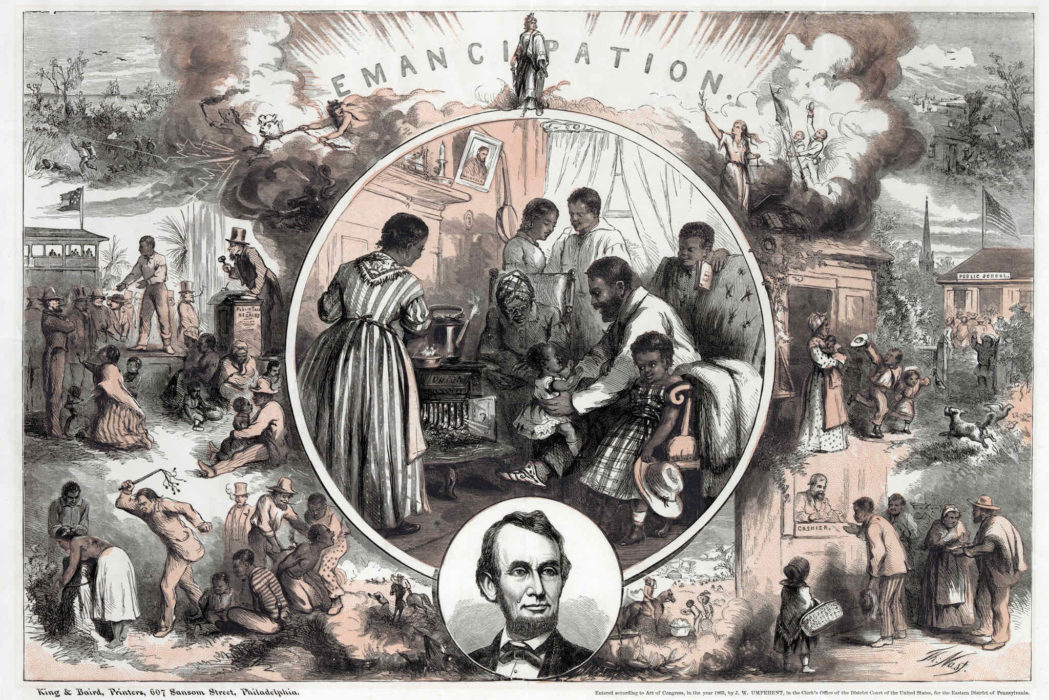

ABRAHAM LINCOLN SIGNED THE Emancipation Proclamation on September 22, 1862. When it came into effect on January 1, 1863, more than three million of the four million slaves in the United States of America were freed. Fifty years later, as ‘Abdu’l-Bahá entered the capital city of the state of Nebraska, which had been named after the Great Emancipator in 1867, celebrations were breaking out in African American communities across the country.

They began at the Metropolitan African Methodist Episcopal Church in Washington, DC, where ‘Abdu’l-Bahá had challenged racial imagery on April 23. A “song jubilee” preceded an address by the new president of Howard University, Dr. Stephen Newman, on “Fifty Years of Freedom.” The observance, the Chicago Defender wrote, “shall stand as a model of a dignified, constructive and inspiring recognition of a day that means everything to the 12,000,000 Negroes on this continent.”

Ten days earlier, readers of the Independent had seen ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s assessment of the moral courage that it had taken for white Americans to go to war to free the slaves. “Never in all the annals of the world do we find such an instance of national self-sacrifice as was displayed here during the Civil War,” he said. “Americans who had never seen a weapon used in anger left their homes and peaceful pursuits, took up arms, bore utmost hardships, braved utmost dangers, gave up all they held dear, and finally their lives, in order that slaves might be free.” In his interview, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá called attention to the talk he had given at Howard University, America’s leading black university. “I told them that they must be very good to the white race of America,” ‘Abdu’l-Bahá said, “that they must never forget to be grateful and thankful.” Likewise, “The white people must treat those whom they have freed with justness and firmness, but also with perfect love.”

Sixteen years later, in 1938, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s grandson, Shoghi Effendi, elaborated on the mutual demands that ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s statements on race placed on both the black and the white citizens of America. “Let neither think that the solution of so vast a problem is a matter that exclusively concerns the other,” he wrote in a letter to the Bahá’ís in the United States.

“Let the white make a supreme effort in their resolve to contribute their share to the solution of this problem,” Shoghi Effendi told them, “to abandon once for all their usually inherent and at times subconscious sense of superiority, to correct their tendency towards revealing a patronizing attitude towards the members of the other race, to persuade them through their intimate, spontaneous and informal association with them of the genuineness of their friendship and the sincerity of their intentions, and to master their impatience of any lack of responsiveness on the part of a people who have received, for so long a period, such grievous and slow-healing wounds.”

On the other hand, Shoghi Effendi wrote, “Let the Negroes, through a corresponding effort on their part, show by every means in their power the warmth of their response, their readiness to forget the past, and their ability to wipe out every trace of suspicion that may still linger in their hearts and minds.”

“Let neither think,” he emphasized, “that anything short of genuine love, extreme patience, true humility, consummate tact, sound initiative, mature wisdom, and deliberate, persistent, and prayerful effort, can succeed in blotting out the stain which this patent evil has left on the fair name of their common country.”

Read President Lincoln’s Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, issued on September 22, 1862 — 150 years ago today.