THE LATE MORNING SUNLIGHT filtered down through opalescent windows and settled on the soft features of Rabbi Martin A. Meyer. At 10:45 a.m. on the cool morning of Saturday, October 12, 1912, he stood upon his pulpit, hand-carved from weathered oak, and looked out over two thousand members of his congregation. They filled the majestic sanctuary of San Francisco’s Temple Emanu-El.

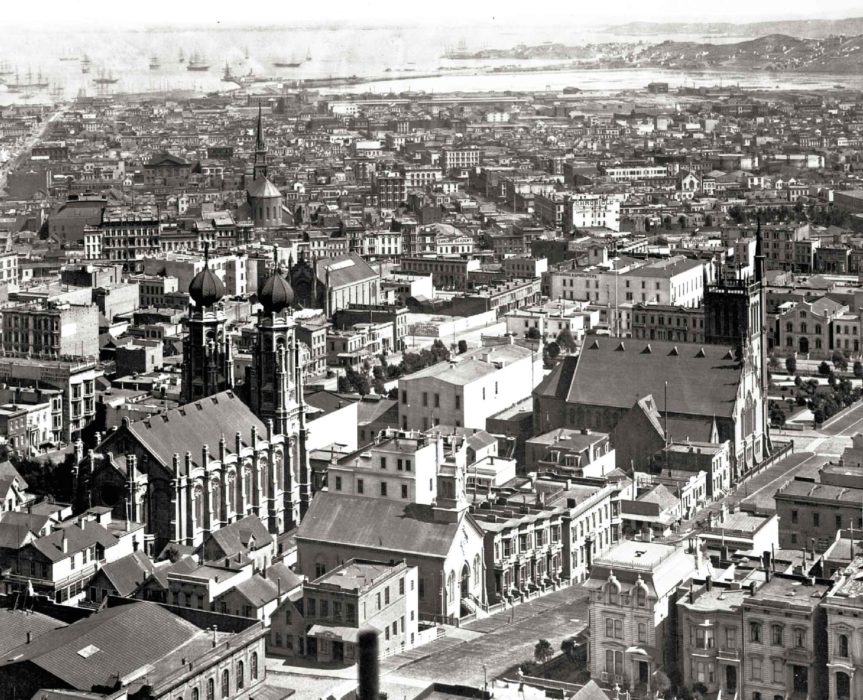

The massive Gothic Revival synagogue, built in the 1860s, was one of the largest vaulted chambers ever constructed in the state of California. Two octagonal towers shot up at the temple’s front corners on Sutter Street, supporting bronze-plated Russian domes that impressed themselves on the city’s skyline. The vaults and the domes had come crashing down on the fateful morning of April 18, 1906, and the temple had burned to its skeleton in the fires. But just sixteen months later Temple Emanu-El rose again from the ashes: squat towers now stood where the domes had been, a ceiling of Oregon pine replaced the vaults, and chandeliers hung down in the shape of six-pointed stars.

“It is a privilege, and a very high privilege indeed,” Rabbi Meyer said, “to welcome in our midst this morning Abdul Baha, a great teacher of our age and generation. . . . Abdul Baha is the representative of one of the religious systems of life, and it appeals to us Jews, because we Jews feel that we have fathered that ideal throughout the centuries of men.”

The Progressive Era had been as much a period of change for the Jewish community in America as it was for the rest of the nation. German-American Jews found their enlightened Reform ideals challenged by the poor, ragged orthodox Jewish immigrants who swarmed into America from Russia and Eastern Europe. The young Rabbi Meyer — tall, blonde, handsome, a San Francisco native, and only thirty-four years old — walked a delicate line. He bridged religious boundaries on social justice issues, but felt that San Francisco’s Reform community, in order to accommodate to the Gentile society around them, had slipped their commitment to traditions that were central to Jewish identity. They knew little about Jewish rites and artifacts, and too many of them celebrated Christmas and Easter, but not Hanukkah or The Passover. Instead, Rabbi Meyer pinned his hopes on the Eastern European Jews, who wanted to remain Jewish because they felt the call of blood and tradition.

So when ‘Abdu’l-Bahá mounted the rostrum with his translator, stood between two palm trees in front of the curtain that concealed the Ark, and invited the congregation to explore religion’s civilizing force, he spoke to a tension at the center of their religious life. “We should investigate religion as seekers of truth,” he said. “When we do so, we find that religion is the cause of progress and development.”

Over the next ten minutes, he recalled the signal events of Jewish history: the founding of the nation by Abraham; its flourishing under Isaac, Jacob, and Joseph; the captivity in Egypt; the rise of a high Israelite civilization under David and Solomon, distinguished by its moral culture, arts and sciences, philosophy, and craftsmanship. Even the philosophers of Greece traveled to the Holy Land to study at the feet of the children of Israel, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá said. “A Cause which changed such a weak people into a powerful nation,” he observed, “makes it evident that religion is a source of honor and progress for humanity, a foundation for eternal happiness.”

But even as it transforms civilization, religion itself is continuously transforming. While the spiritual essentials, the moral core of religions are eternal, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá argued, its social laws are “laid down in every Dispensation in accordance with the needs of the age and are subject to change.” The Reform congregation at Temple Emanu-El may have agreed, believing as they did that Jewish traditions should be modernized and compatible with the surrounding culture.

Then ‘Abdu’l-Bahá broached another subject, this one far more delicate. Just as the Jewish prophets had reclaimed a lost people and turned them into a mighty society, so had Jesus and Muhammad. “When the light of Muhammad dawned,” he said, “the darkness of ignorance was dispelled from the Arabian desert. In a short space of time those barbarous tribes reached a degree of civilization which extended to Spain and was established in Baghdad and influenced the people of Europe. What proof is there concerning His prophethood greater than this?”

“The Christians believe in Moses as a Prophet of God. The Muslims are believers in Moses and praise Him highly. Has any harm come to Christians and Muslims because they have admitted the validity of Moses? No, on the contrary, their acceptance of Moses and confirmation of the Torah prove that they have been fair-minded.”

Rabbi Meyer wiped a bead of perspiration from his forehead.

“Why should not the children of Israel praise now Christ and Muhammad?” ‘Abdu’l-Bahá asked. He was not suggesting that they become Christians, but that vocal respect for the founders of the great religions was the first essential step in setting aside religious prejudice. “As it is possible to do away with warfare and massacre with a small measure of liberalism in the world, why not do it? Thus bonds are established which can unite the hearts of men.”

On Saturday, October 12, 1912, at Temple Emanu-El, Rabbi Martin Abraham Meyer hosted ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s longest talk in America. He was far more interested in practice than theory, and so for the next eleven years, until his untimely death in 1923, Rabbi Meyer would work to heal the rifts in the Jewish community and build bridges with nearby Christian churches. “He was proper,” scholar Fred Rosenbaum writes, “but capable on occasion of taking great risks, in exposing the inadequacy . . . of his flock’s religious expression.”

‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s impression of the young Rabbi was simpler. “Rabbi Meyer,” he said, “is a very broad-minded man.”