‘ABDU’L-BAHÁ WAS CONVERSING IN Phoebe Hearst’s garden in Pleasanton, California, when it happened.

The news “flashed outward along telephone and telegraph wires, jolting every night editor in the country,” writes biographer Edmund Morris, “penetrating even into the Casino Theatre in New York, where Edith Roosevelt sat watching Johann Strauss’s The Merry Countess. She emerged from the side entrance weeping. ‘Take me to where I can talk to him or hear from him at once.’ A police escort whisked her to the Progressive National Headquarters in the Manhattan Hotel, which had an open line to Milwaukee.” The presidential election was only three weeks away.

The former President had strolled out of the Gilpatrick Hotel on Third Street in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, at exactly 8:10 p.m. on Monday, October 14, 1912. He had walked across the pavement, and sat down in his customary back seat on the right-hand side of his car — a roofless, seven-seater that would take him to the Milwaukee Auditorium for his speech. In response to the cheering crowd, which formed a dense mass for a block in every direction, Roosevelt stood and waved his hat. There was a glint of steel; a shot rang out. Seven feet from the car a “weedy little man,” Mr. John. F. Schrank of 370 10th Street, New York, stood holding a .38-caliber Smith & Wesson revolver, still smoking from the discharge.

The bullet, Morris writes “lay embedded against the fourth right rib, four inches from the sternum. In its upward and inward trajectory, straight toward the heart, it had had to pass through Roosevelt’s dense overcoat into his suit jacket pocket, then through a hundred glazed pages of his bifolded speech into his vest pocket, which contained a steel-reinforced spectacle case three layers thick, and on through two webs of suspender belt, shirt fabric, and undershirt flannel, before eventually finding skin and bone.”

Teddy’s knees bent, he reached for the folded canopy of the convertible to steady himself, and then he hoisted himself back up. Below him on the pavement he saw one of his stenographers, Elbert Martin, trying to break the would-be assassin’s neck. “Don’t hurt him,” Roosevelt yelled. He placed his hands gently on either side of the man’s face, peered into his eyes, and asked, “What did you do it for?” His query received only a blank stare. “Oh, what’s the use? Turn him over to the police.”

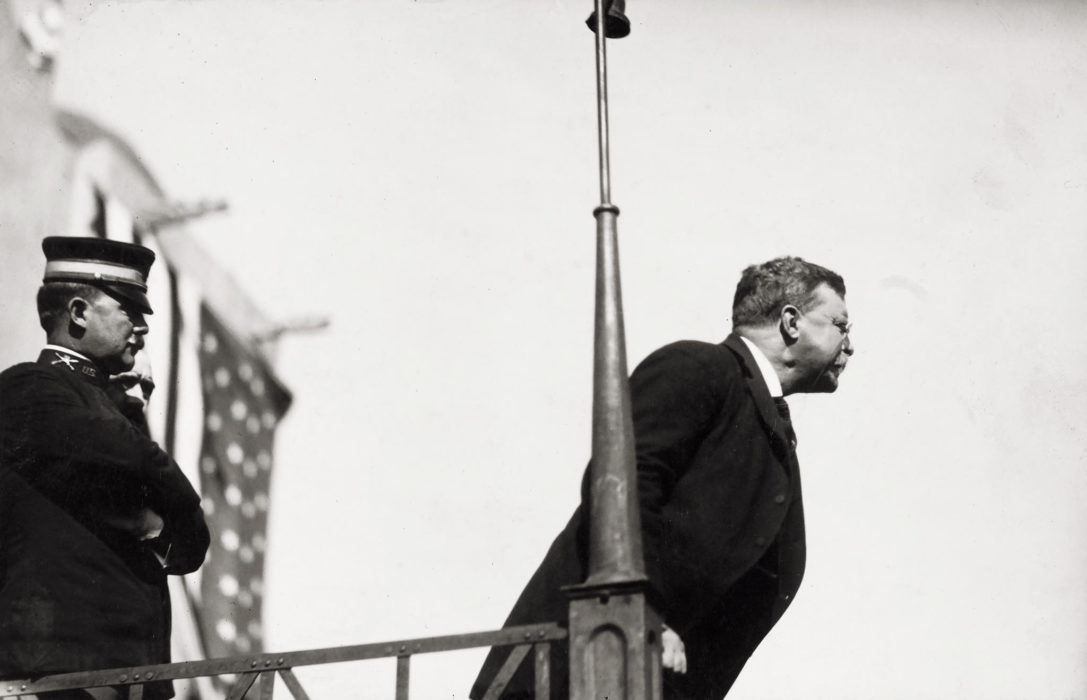

Urged by his staff to go the hospital, Roosevelt insisted on keeping his appointment at the Auditorium instead. “You get me to that speech,” he rasped. And so, with a cracked rib, bleeding from a dime-sized hole in his chest, Roosevelt shook off his handlers and mounted the stage. It was only when he opened his fifty-page speech and saw its “double starburst perforation” that the emotions of what had happened finally hit him.

“Friends, I shall have to ask you to be as quiet as possible,” he began, in this era before microphones. “I do not know whether you fully understand that I have just been shot, but it takes more than that to kill a Bull Moose.” He went on for an hour and fifteen minutes, throwing down leaf after leaf of his speech as he finished each page — fifty of them in all.

Roosevelt did not know the man who shot him, he said, but he was not surprised that the escalating rhetoric and personal attacks, which had suddenly become commonplace in this election, had led to violence. “I wish to say seriously to all the daily newspapers, to the republican, the democratic and the socialist parties that they cannot month in and month out and year in and year out make the kind of untruthful, of bitter assault that they have made and not expect that brutal violent natures . . . will be unaffected by it.”