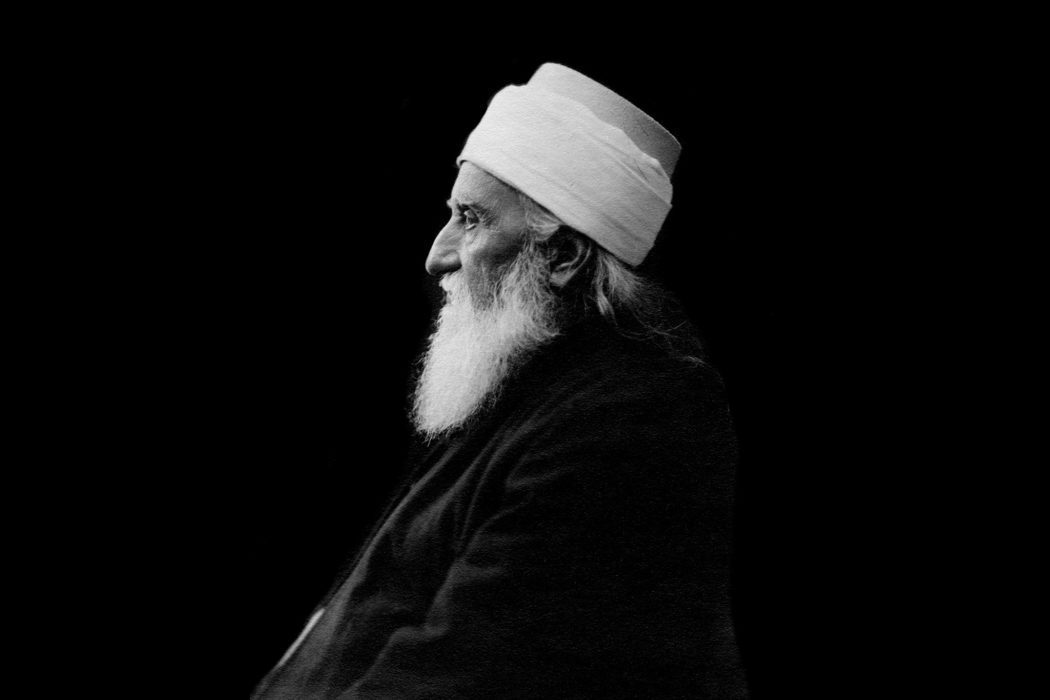

‘ABDU’L-BAHÁ’S JOURNEY ACROSS America is almost complete. One hundred years ago today he rode the train from Sacramento to Salt Lake City, the first leg of his return trip across the continent. In thirty-nine days he will step aboard the SS Celtic, at the White Star Line piers along the Hudson River near West 18th Street in Manhattan, and sail for Liverpool.

That leaves us less than six weeks to bring to a conclusion all the many threads we have explored in the past 200 days. It’s a race to the finish, and we still have a lot of things to say.

The year 1912 turned out to be a watershed in American history, its traces cascading forward into the coming twentieth century. It began with a group of Polish women weavers shutting down their looms and walking out of the Everett Cotton Mill in Lawrence, Massachusetts, on January 11, shouting “Short pay! Short pay!” They had just picked up their pay envelopes to find they were thirty-two cents short, enough to buy several loaves of bread. By the end of the month 20,000 millworkers were on strike in Lawrence, the government had declared martial law, and a century-long battle between regular people and corporate power had begun.

There could hardly have been a better time for Teddy Roosevelt to throw his hat into the ring to seek a third term. But by the end of October, and in spite of the hype that newspaper offices continued to pump out each day, the outcome of the presidential race was a foregone conclusion. By walking out of the Republican National Convention with 344 delegates on June 22, Theodore Roosevelt had split the Republican vote, handing the election over to the Democratic Party, which proceeded to nominate the progressive Governor of New Jersey, Woodrow Wilson, as its candidate.

Under Wilson, the Progressive Movement’s agenda was about to shift the nation, but it was not to last. The decline of the Progressives, and the collapse of the political unity in which they had invested their hopes, is one of the tragedies of modern America. As we shall see in the coming weeks, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá had argued time and again that political agreement would not be enough to solve the pressing problems of this rising industrial nation.

For ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, the whole ballgame was about what “human nature” truly meant. As we bring these 239 days to a close, we will engage with this overarching theme of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s American conversation, and explore how American history unfolded in the years after 1912’s watershed moment.