“HIS VISIT TO WASHINGTON has been a triumphal march,” the Chicago Defender announced in its edition of Saturday, May 4, 1912. America’s most influential black weekly newspaper was reporting on ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s first visit to Washington, DC. “Southern people whose hearts were once filled with the most bitter prejudices against their brothers in black, have publicly acknowledged their change of heart and now treat the colored people as brother indeed.” “He has met and conquered southern prejudices.”

That might have been a bit optimistic. Even before he arrived in America, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá had already shown his grasp of how deeply these “southern prejudices” ran; they certainly could not be conquered overnight, and they remain with us in diminished form today. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá neither harbored any illusions about the systemic crisis that the race problem posed for America’s social fabric, nor understated how much deep personal soul-searching and mutual goodwill would be necessary to weed out such an entrenched pattern of life. The problem was urgent, and required immediate, systematic intervention.

“Until these prejudices are entirely removed from the people of the world,” he later wrote, “the realm of humanity will not find rest. Nay, rather, discord and bloodshed will be increased day by day, and the foundation of the prosperity of the world of man will be destroyed.” “Now is the time for the Americans to take up this matter and unite both the white and colored races. Otherwise, hasten ye towards destruction! Hasten ye toward devastation!” “Indeed, there is a greater danger than only the shedding of blood. It is the destruction of America.”

During his first trip to Washington, from April 20 to 27, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá had begun to weave together a strategy aimed not just at promoting economic and civil rights for African Americans, but at healing the centuries of mistrust that racial prejudice had perpetuated between white and black. It amounted to a frontal assault against the racial ideologies that legitimized the color line in American life.

At Howard University on the morning of April 23, and at the Metropolitan African Methodist Episcopal Church that evening, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá had begun to elaborate a new language of race — a new set of racial images and metaphors — that consciously contradicted the popular associations of the racial term “black” with evil, darkness, and filth. “In the clustered jewels of the races,” he said in one of many such statements, “may the blacks be as sapphires and rubies and the whites as diamonds and pearls. The composite beauty of humanity will be witnessed in their unity and blending.”

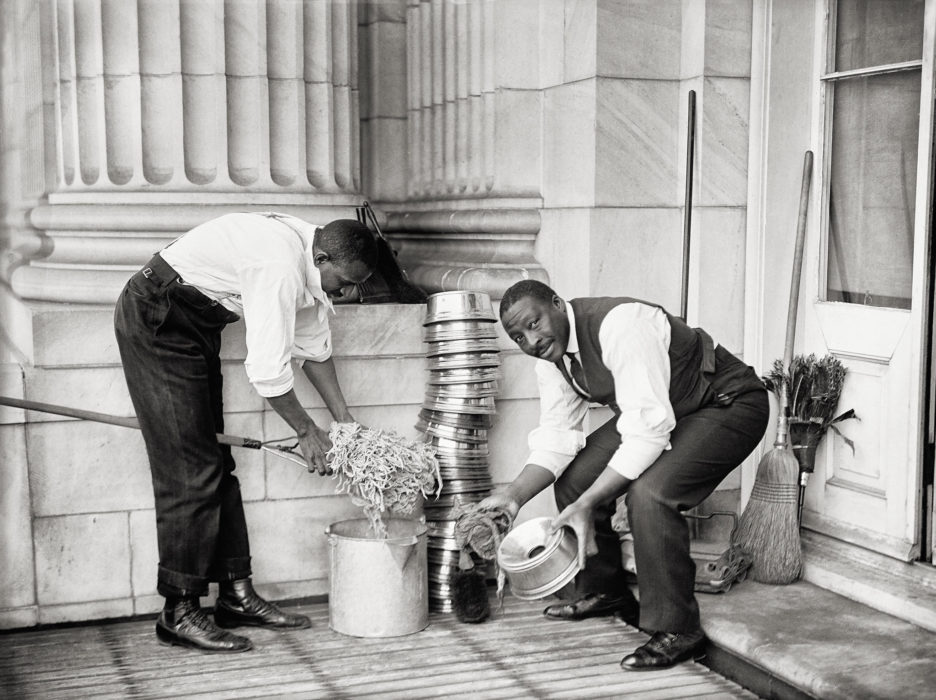

appeared in this issue. Chicago Defender

In addition to his compelling use of language, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá found opportunities to put his racial discourse into practice: seating a black man in the place of honor at a diplomatic dinner to which the man, being a Negro, had not been invited; insisting that meetings should be mixed race; emphasizing that both white and blacks had to change their behavior in difficult ways for unity to be constructed out of the divisiveness of the present; and by coming out for interracial marriage in 1912 America.

While ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s discourse on race hadn’t yet “conquered” the southern prejudices the Defender identified, they had already begun to work change in the lives of many of the individuals who surrounded him. Delegates to the Bahá’í Temple Unity convention elected Louis Gregory to their national council just days after ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s opening salvo in Washington. Agnes Parsons, whose home near Dupont Circle was one of the centers of social Washington, began 1912 without any contact with the African American life of the city. Her diary of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s days in Washington omits mention of most of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s engagement with the issue of race. Yet she opened her home to black guests, and, within a few years, was energetically taking the lead in organizing nationwide Race Unity Conferences, having been asked to do so by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá.

On November 10, 1912, during his final visit to the capital, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá reprised his theme at a mixed-race gathering at the home of Pauline and Joseph Hannen: “In the sight of God there is no distinction between whites and blacks; all are as one. . . . How then can man be limited and influenced by racial colors? The important thing is to realize that all are human, all are one progeny of Adam. Inasmuch as they are all one family, why should they be separated?”

“Excellence does not depend upon color,” Abdu’l-Bahá argued. “Character is the true criterion of humanity.”