“HAVING TRAVELED FROM COAST to coast,” ‘Abdu’l-Bahá announced on Election Day in Cincinnati, “I find the United States of America vast and progressive, the government just and equitable, the nation noble and independent.”

During his eight months in America, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá had engaged a vast, diverse audience of Americans in conversation about the issues they felt were central to the future of their nation. He had praised “the optimism of this great country,” and the “quick perception, intelligence and understanding,” of the American people. “They are not content to stand still. They are most energetic and progressive.” “I find religion, high ideals, broad sympathy with humanity, benevolence and kindness widespread here,” he said, “and my hope is that America will lead in the movement for universal peace.”

The Americans ‘Abdu’l-Bahá met in 1912 lived on the cresting heights of a decades-long wave of optimism generated by faith in the ability of new sciences — statistics, economics, sociology, and psychology prominent among them — to solve the injustices of the industrial age. Between 1890 and 1920, millions of Americans, calling themselves “progressives,” campaigned against child labor, for more representative government, against corporate control of the economy, for worker’s rights and women’s suffrage. “Progressivism,” historians Arthur Link and Richard McCormick wrote, “was the only reform movement ever experienced by the whole American nation.”

These threads coalesced in the presidential election of 1912. It was “a unique moment in the Progressive Era,” writes scholar Brett Flehinger, “because it drew together politicians, social reformers, intellectuals, and economists onto a single stage and produced a many-sided national debate about the future of America’s economic, political, and social structure.”

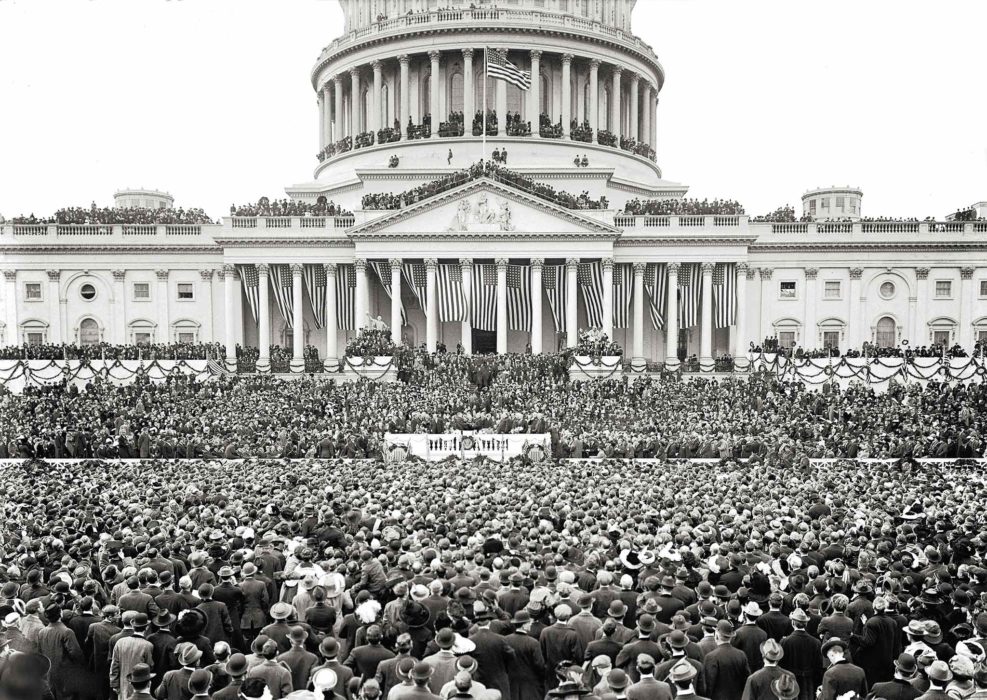

When, on March 4, 1913, Woodrow Wilson stood in front of the east facade of the U.S. Capitol building to take the oath of office, he announced to the American people that the time for change had come. “The Nation has been deeply stirred,” Wilson said in his inaugural address, “stirred by a solemn passion, stirred by the knowledge of wrong, of ideals lost. . . . The feelings with which we face this new age of right and opportunity sweep across our heartstrings like some air out of God’s own presence, where justice and mercy are reconciled and the judge and the brother are one.”

By 1916, the end of Woodrow Wilson’s first term in office, most of the progressives’ agenda had been enacted into law by Congress. They created the Federal Reserve to guard against financial panics, fight unemployment, and protect the American people from the financial power of Wall Street. The Federal Trade Commission (FCC) and the Clayton Antitrust Act prevented large corporations from engaging in unfair or anti-competitive practices. The Farm Loan Act made credit available to small farmers. The Keating-Owen Act took aim at child labor practices. The Adamson Act enforced an eight-hour workday on the railroads. The Seventeenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution provided for the people to elect their Senators directly, instead of having them appointed by state legislatures. Then, in 1920, ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment granted women’s suffrage in national elections.

But ‘Abdu’l-Bahá had argued repeatedly in his conversations that America’s future depended on much more than the legal solutions made possible by tentative political accommodations. Indeed, the hopes of the progressives were soon to be dashed, their ideals disappointed, by new political and social divisions that rose out of the unexpected global war that they never saw coming. “Every reform we have won will be lost if we go into this war,” the President said.

The Progressive Era, then, was a time of both great achievements and tragic shortcomings. In the remaining weeks of our journey, we will look to the years after 1912 to examine the central themes of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s American discourse in light of the successes and failures of the Progressive Movement, and in the broad perspective of America’s twentieth century.