THE WORLD’S RICHEST MAN when 1912 began was a Scottish immigrant from Dunfermline, County Fife, who emigrated with his family to Allegheny, Pennsylvania, at the age of twelve in 1848. He got his first job as a bobbin boy in a local cotton mill when he was thirteen, changing spools of thread twelve hours a day for $1.20 a week. Two years later he was a messenger boy in the Pittsburgh office of the Ohio Telegraph Company: $2.50 per week. At seventeen the Pennsylvania Railroad employed him as a telegraph operator: $25.00 per month. The following year he got his first investment opportunity, ten shares in the Adams Express, for which he had to borrow $500. The returns he reinvested . . . and reinvested . . . and reinvested, slowly built up Andrew Carnegie’s base of capital.

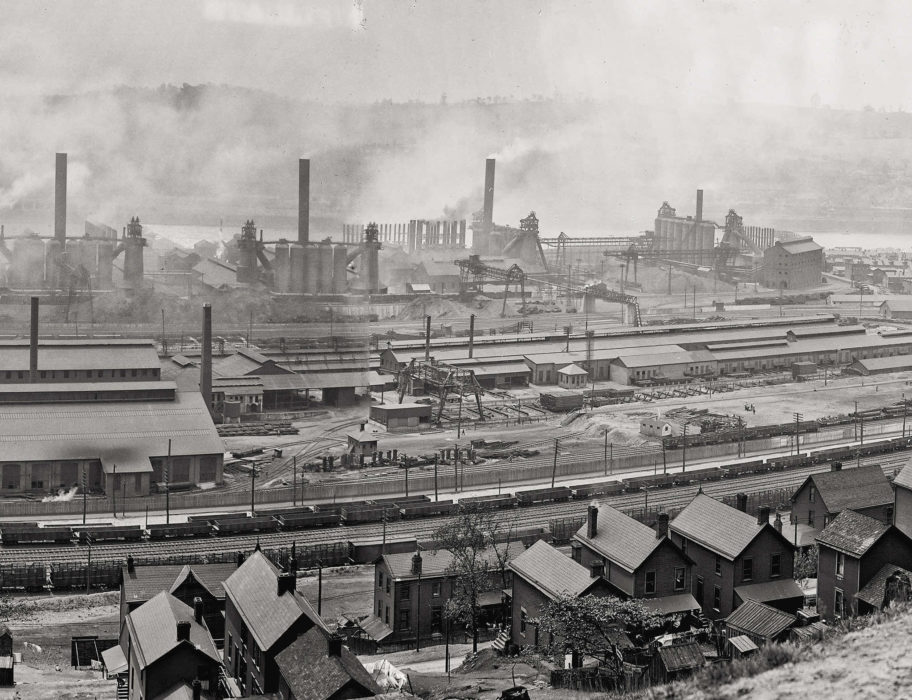

Having spent the Civil War as Superintendent of the Pennsylvania Railroad’s western division—and getting rich on oil investments during the war boom—Andrew Carnegie left the railroad and turned his attention to iron and steel. By adopting the railroads’ cost accounting methods, vertically integrating all his suppliers, driving huge economies of scale, and swiftly adopting new technologies, Carnegie could convert raw iron ore into fine steel twenty-four hours a day with a minimum of skilled workers. By the 1880s he was the largest producer of pig iron, rails, and coke in the world, and he dominated the American steel market, making “most of the steel that built America’s tools, factories, tall buildings, ships, streetcars, and machines.” He retired in 1901 at the age of sixty-six, selling his steel interests to J. P. Morgan for $480 million and becoming the richest man on earth.

But even as he was living the life of a robber baron during the Gilded Age, piling up capital and repressing striking workers, Carnegie was already formulating a different outlook on wealth than most of his tycoon friends. “Man must have no idol,” he wrote, “and the amassing of wealth is one of the worst species of idolatry! No idol is more debasing than the worship of money! . . . To continue much longer overwhelmed by business cares and with most of my thoughts wholly upon the way to make more money in the shortest time, must degrade me beyond hope of permanent recovery.”

‘Abdu’l-Bahá participated in several peace gatherings sponsored by Carnegie, including the Lake Mohonk Conference on International Arbitration, which Carnegie’s millions had underwritten. In November Carnegie called on ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in New York, and, it seems, gave him a copy of his book, The Gospel of Wealth. In it Carnegie had argued for the responsibility the rich had to improve society. Not only should they give away all their wealth, but they had to administer it themselves, focusing their resources on enterprises that would elevate the masses of society “in the forms best calculated to do them lasting good,” not merely frittering it away on indiscriminate charity. In 1900 he refused to establish a peace and arbitration society that a friend had suggested, because he believed that his money would cause harm instead of good. “I am certainly not wrong,” he wrote, “that if it were dependent on any millionaire’s money it would begin as an object of pity and end as one of derision. I wonder that you do not see this. There is nothing that robs a righteous cause of its strength more than a millionaire’s money. Its life is tainted thereby.” He also approved of the high estate taxes that had been established in England. “By taxing estates heavily at death,” Carnegie wrote, “the State marks its condemnation of the selfish millionaire’s unworthy life. It is desirable that nations should go much further in this direction.”

‘Abdu’l-Bahá had upheld similar views on the responsibilities of the wealthy at least since 1875, when he wrote The Secret of Divine Civilization, an open letter to Iranians proposing an ambitious program of social, legal, religious, and educational reform. “Wealth is praiseworthy in the highest degree,” ‘Abdu’l-Bahá wrote, “if it is acquired by an individual’s own efforts and the grace of God, in commerce, agriculture, art and industry, and if it be expended for philanthropic purposes. Above all, if a judicious and resourceful individual should initiate measures which would universally enrich the masses of the people, there could be no undertaking greater than this.”

‘Abdu’l-Bahá read The Gospel of Wealth and wrote back to Andrew Carnegie on January 10, 1913, shortly after he had arrived in London after his American journey. Carnegie was so impressed with the letter that he sent it to the New York Times. In his reply, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá contributed the observation that to redistribute wealth successfully it was essential to make sure that the act of doing so did not create further rifts between the classes.

“To state the matter briefly,” he wrote, “the Teachings of Bahá’u’lláh advocate voluntary sharing, and this is a greater thing than the equalization of wealth. For equalization must be imposed from without, while sharing is a matter of free choice. Man reacheth perfection through good deeds, voluntarily performed, not through good deeds the doing of which was forced upon him.” Although he believed redistributive legislation was necessary, he argued that the ultimate solution to the problem of rich and poor was that the rich should change their fundamental attitudes, and go out of their way to give lavishly without being coerced. “For the harvest of force is turmoil and the ruin of the social order. On the other hand voluntary sharing, the freely-chosen expending of one’s substance, leadeth to society’s comfort and peace. It lighteth up the world; it bestoweth honour upon humankind.”

By the time the two men met in November, 1912, Carnegie had already built hundreds of public libraries, given pensions to his former By the time the two men met in November, 1912, Carnegie had already built hundreds of public libraries, given pensions to retired college professors, funded Booker T. Washington’s Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, and endowed Carnegie Mellon University and Britain’s University of Birmingham. On December 14, 1910, he set aside his earlier skepticism about endowing a peace organization, and established the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace:

Gentlemen—I have transferred to you as trustees of the Carnegie Peace Fund $10,000,000 in 5 per cent. first mortgage bonds . . . the revenue of which is to be administered by you to hasten the abolition of international war, the foulest blot on our civilization. Although we no longer eat our fellow men nor torture prisoners, nor sack cities, killing their inhabitants, we still kill each other in war like barbarians. Only wild beasts are excusable for doing that in this, the Twentieth Century of the Christian Era, for the crime of war is inherent, since it decides not in favor of the right but always of the strong.

In May, 1915, in the midst of the war, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá sent a second letter, which Carnegie also printed in the Times. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s praise of the philanthropist was effusive. “A number of souls who were doctrinaires and unpractical thinkers worked for the realization of this most exalted aim and good cause [i.e. a basis for universal peace], but they were doomed to failure, save that lofty personage [Carnegie] who has been and still is promoting the matter of international arbitration and general conciliation through words, deeds, self-sacrifice and the generous donation of wealth and property.” “Rest thou assured,” ‘Abdu’l-Bahá wrote, “that thou wilt become confirmed and assisted in the accomplishment of this most resplendent service and in this mortal world thou shalt lay the foundation of an immortal, everlasting edifice and in the end thou wilt sit upon the throne of incorruptible glory in the Kingdom of God.”

Today’s richest man, the Mexican telecom magnate Carlos Slim [as of 2012], enjoys a net worth of $69 billion, and Bill Gates of Microsoft, the second on Forbes magazine’s 2012 World’s Billionaires List, clocks in at $61 billion. Back in 2007, two Forbes writers published a list of the wealthiest Americans of the past, comparing their relative wealth expressed as a percentage of inflation-adjusted Gross Domestic Product (GDP). They estimated Andrew Carnegie’s personal fortune at $281.2 billion in 2006 dollars, or, in other words, almost five Bill Gateses. And by the time Carnegie died in 1919, he had given almost ninety percent of it away.

On April 15, 1912, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s fifth day in America, he received Hudson Maxim, the arms inventor, for an interview at the Hotel Ansonia. In the course of the conversation ‘Abdu’l-Bahá encouraged Maxim to give up his business interests— supplying raw materials for the armaments of a militarizing world—and to turn his efforts to building peace. “Then will your life become pregnant and productive with really great results,” ‘Abdu’l-Bahá told him. “God will be pleased with you and from every standpoint of estimation you will be a perfect man.” When ‘Abdu’l-Bahá met Andrew Carnegie a few days before he sailed from New York, he met an American who had done exactly that.