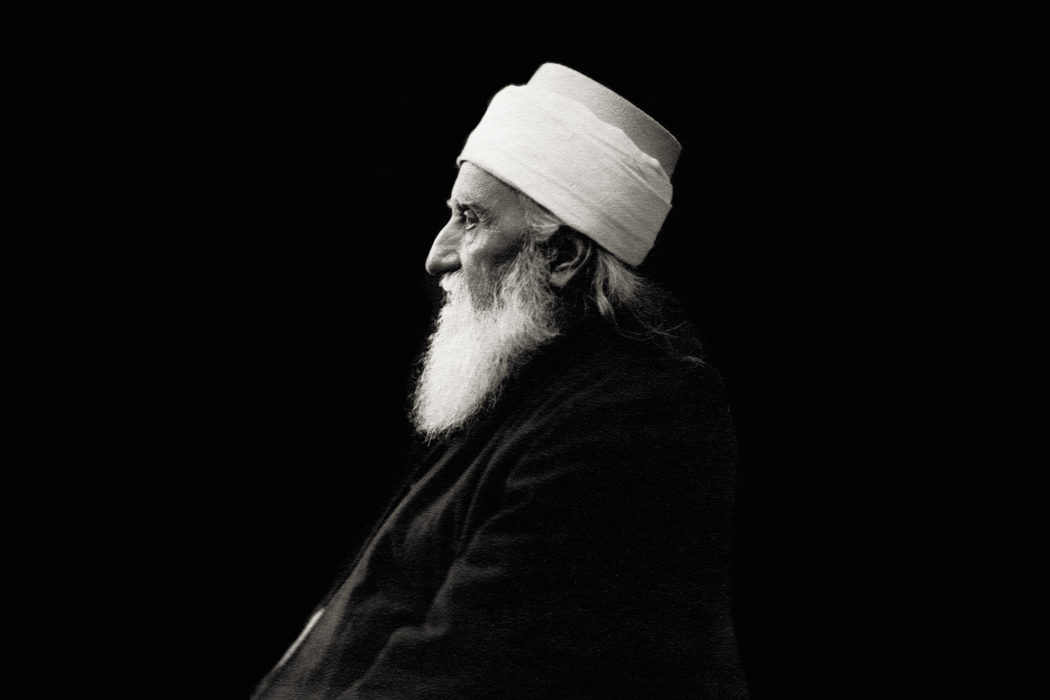

“PEACE, PEACE, THE LIPS of potentates and peoples unceasingly proclaim,” ‘Abdu’l-Bahá was heard to say in the months following the First World War, “whereas the fire of unquenched hatreds still smoulders in their hearts.”

‘Abdu’l-Bahá began to advise Americans against putting too much faith in the outcome of the Paris Peace Conference before it had even begun. “Although the representatives of various governments are assembled in Paris in order to lay the foundations of Universal Peace,” he wrote to a friend in Portland, Oregon, on January 10, 1919, two days before the conference convened, “yet misunderstanding . . . is still predominant and self-interest still prevails. In such an atmosphere, Universal Peace will not be practicable, nay rather, fresh difficulties will arise.”

He argued the same point in a long letter to the Central Organization for a Durable Peace, a commission set up in 1915 at The Hague to plan for an eventual postwar reconciliation. Fannie Fern Andrews, one of the American members of the commission, explained its purpose in front of the American Academy of Political and Social Science in 1916. “When the representatives of the states come together in the midst of the wreck and desolation left by the war, their task will be almost overwhelming,” she said. “The fundamental basis of the new world order which must come after the present war must be laid today.” The Organization asked ‘Abdu’l-Bahá to present his proposals for global peace in February, 1916, but he was cut off behind enemy lines and didn’t receive the letter until after the war ended.

The central message of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s letter, which he sent to The Hague from Haifa on December 17, 1919, was that achieving universal peace required a more comprehensive approach than customary international diplomacy would permit. “If the question is restricted to Universal Peace alone the remarkable results which are expected and desired will not be attained,” he wrote. “The scope of Universal Peace must be such that all the communities and religions may find their highest wish realized in it.”

Peace, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá argued, required a massive social transformation of the depth and scope that his father, Bahá’u’lláh, had proposed: the consciousness of the whole human race being a single people; the central motivating role of non-dogmatic, reasonable religious belief; deliberately weeding out religious, racial, class, partisan, and nationalistic prejudices; complete equality between the sexes; universal education for children; the conviction that the whole surface of the earth is one native land. National boundaries, he argued, are imaginary lines that emerged during the early history of civilization to serve the selfish interests of a few individuals, and these in turn led to “intense enmity, bloodshed and rapacity in subsequent centuries.” “In the same way,” ‘Abdu’l-Bahá emphasized, “this will continue indefinitely, and if this conception of patriotism remains limited within a certain circle, it will be the primary cause of the world’s destruction.”

Then ‘Abdu’l-Bahá addressed the collective security arrangements, or the lack of them, that had emerged out of Paris. “Although the League of Nations has been brought into existence, yet it is incapable of establishing Universal Peace.” In its place, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá proposed an institution far more powerful than either the League or the United Nations that succeeded it: a “Supreme Tribunal” whose powers Bahá’u’lláh had described. The key distinctions he outlined to the commission focused on the institution’s legitimacy and its jurisdiction.

First, the members of this supreme global body would have to be elected from among a pool of candidates proposed by each country’s parliament. The candidates from each country, the numbers of them being determined relative to population, would have to be confirmed by the other national organs of government in their states—the upper house, the congress, the cabinet, the president, the monarch—so their legitimacy would be indisputable: “all mankind will thus have a share therein, for every one of these delegates is fully representative of his nation.” This strong legitimacy would translate into effective action, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá argued, because “When the Supreme Tribunal gives a ruling on any international question, either unanimously or by majority-rule, there will no longer be any pretext for the plaintiff or ground of objection for the defendant.” Should any country ignore the Tribunal’s ruling “the rest of the nations will rise up against it,” he wrote, providing the power of enforcement.

“Consider what a firm foundation this is!” he said. “But by a limited and restricted League the purpose will not be realized as it ought and should. This is the truth about the situation. . . .”

The new world order that emerged in Paris, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá believed, was inadequate to meet even the immediate challenges the world faced from new ideologies of power that were still an afterthought in 1919. “Movements, newly-born and world-wide in their range, will exert their utmost effort for the advancement of their designs,” he insisted in January, 1920. “The Movement of the Left will acquire great importance. Its influence will spread.”

“The ills from which the world now suffers,” ‘Abdu’l-Bahá wrote, “will multiply; the gloom which envelops it will deepen. The Balkans will remain discontented. Its restlessness will increase. The vanquished Powers will continue to agitate. They will resort to every measure that may rekindle the flame of war.”