THE POSH HOTEL SCHENLEY rises ten stories high in red brick, on top of a green hill surrounded by trees on the outskirts of Pittsburgh. The founders of US Steel met here to concoct the largest corporation in American history. It’s where the famous “Meal of Millionaires” took place in 1901: eighty-nine of them assembled in a single room.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá speaks of the “signs of prosperity everywhere” in America. They surround him at the Schenley. In 1901, J. P. Morgan bought Carnegie Steel from Pittsburgh’s most famous immigrant for $492,000,000. It made Andrew Carnegie the richest man in the world.

But, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá says, “No matter how far the material world advances, it cannot establish the happiness of mankind. Only when spiritual and material civilization are linked and coordinated will happiness be assured.”

As usual, his friends picked the Schenley for him to stay in before he arrived in Pittsburgh. Glossy marble pillars surround the impressive skyscraper. Chandeliers hang from its upstretched ceilings like clusters of diamond berries. Perhaps ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s friends, knowing his history as an exile and prisoner, wanted him to enjoy luxury for a change.

When ‘Abdu’l-Bahá arrived in Pittsburgh today — May 7, 1912 — his friends kept asking him if he liked his rooms. Each time he was asked he repeated “Very good! Very good!” But when they left he turned to one of his Persian travel companions, Dr. Zia Bagdadi, and said, “The friends are anxious to know if I like these rooms! They do not know what we had to go through in the past.” He recounted the time he spent in ‘Akká, where his family was forced to occupy a single prison cell with several other families for two years. He was unable to prevent the deaths of many of the prisoners from illness..

At the Schenley Hotel, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá called for justice in all economic affairs. He said: “The fourth principle or teaching of Bahá’u’lláh is the readjustment and equalization of the economic standards of mankind.”

‘Abdu’l-Bahá has been both extremely wealthy and extremely poor. As a child, his family was one of the wealthiest in Persia, and he lived in lavish luxury. But when he was eight years old, they were suddenly stripped of their wealth, lands, and houses, because of their religious beliefs, and left homeless overnight. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s mother, Asiyih, would pull the gold buttons off her clothes and sell them in order to feed her children. Once, all she could offer her eldest son to eat was a handful of flour.

So when ‘Abdu’l-Bahá talks about the moral implications of an unjust economic order, he speaks from experience on both sides of the tracks.

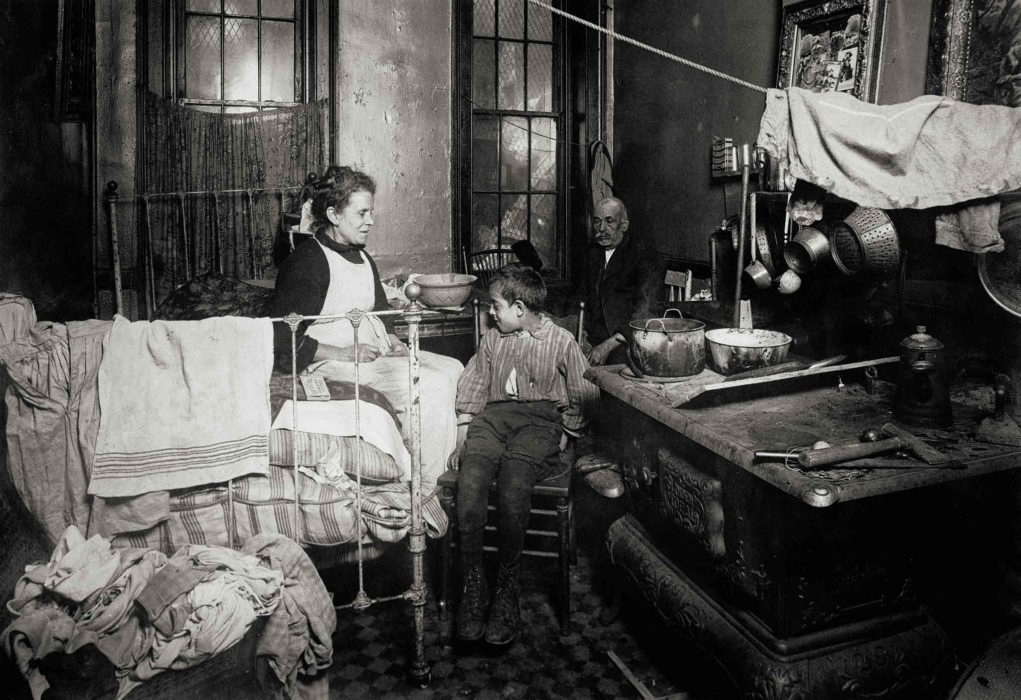

“It is evident that under present systems and conditions of government,” he said, “the poor are subject to the greatest need and distress while others more fortunate live in luxury and plenty far beyond their actual necessities. This drastic inequality is “one of the deep and vital problems of society.”

The solution? “The remedy must be legislative readjustment of conditions.” But, he says, “The rich too must be merciful to the poor, contributing from willing hearts to their needs without being forced or compelled to do so.”

By combining these approaches — uncoerced generosity by the rich and laws that prevent economic extremes — ‘Abdu’l-Bahá tells his audience: “The composure of the world will be assured.”