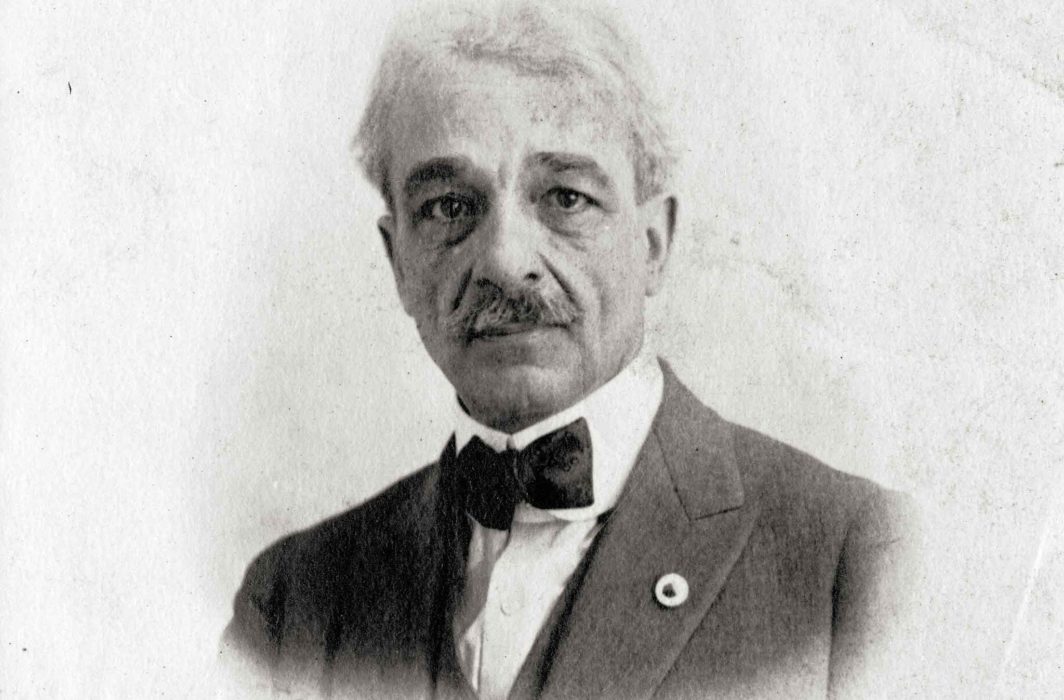

“IT WAS AN IMPRESSIVE, even to me a thrilling sight,” Howard Colby Ives later wrote, “when the majestic figure of the Master strode up the aisle of the Brotherhood Church.” It was Sunday, May 19, 1912.

Although Ives was employed as a Unitarian pastor in Summit, New Jersey, he had started the Brotherhood Church on his own. Every Sunday evening he held a service in the large hall at the Masonic Temple at Bergen and Fairview Avenues in Jersey City. On this evening, 500 people were waiting to hear ‘Abdu’l-Bahá.

Ives seated ‘Abdu’l-Bahá directly behind the pulpit and began an introduction. “You know something of his life probably,” Ives told the congregation. “He has spent over forty years in prison. . . . He comes out of this prison and steps into the great societies of Paris, London and America. He finds the world open to receive him. He comes with nothing to back him. He has no great letters of credit; he does not even speak our language.”

Five weeks before, Ives had stood amid 300 people wedged into a crowded home on West End Avenue in the Upper West Side, just a few hours after ‘Abdu’l-Bahá had arrived in America. All he could get that day were a few glimpses of the visitor. He peered over a shoulder and saw ‘Abdu’l-Bahá seated, wearing a cream-colored turban and a white oriental robe, and accepting a cup of tea. But what impressed him the most was the silence in the room.

It was something he often noticed around this visiting Persian. “I looked at this stillness, this quietude, this immeasurable calm in ‘Abdu’l-Bahá and it filled me with a restless longing akin to despair.” The pattern runs throughout his autobiography: the middle-aged clergyman thrown into turmoil as he contemplates the inscrutable serenity of the former prisoner.

He felt it again at the Brotherhood Church on May 19. After Ives’s introduction, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá took the pulpit. “Because this is called the Church of Brotherhood,” the Master began, “I wish to speak upon the brotherhood of mankind.”

Ives would later reflect: “As that beautifully resonant voice rang through the room, accenting with an emphasis I had never before heard the word Brotherhood, shame crept into my heart. Surely this Man recognized connotations to that word which I, who had named the church, had never known.”

Howard Colby Ives had been unable to meet ‘Abdu’l-Bahá on that first day on the Upper West Side. And so he came early to the Hotel Ansonia on April 12, the next morning. But he didn’t have an appointment and another crowd was already waiting. Then ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s eyes met Ives’s.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s right hand grasped Ives’s, drew him into an adjoining room, and, with his left hand, he waved everyone else out — including his translator, Dr. Fareed. The two men sat quietly for a long while, in two chairs facing each other at the bay window. Finally, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá broke the silence — in English.

“Softly came the assurance that I was His very dear son.” The Reverend began to weep. “A long-pent stream was at last undammed,” he commented. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá pressed his two thumbs to Ives’s eyes and wiped the tears away.

Five weeks later, Ives sat among the congregation at the Brotherhood Church and watched ‘Abdu’l-Bahá look down at him from the pulpit and smile. He listened as ‘Abdu’l-Bahá described the disciples that had circled around Bahá’u’lláh: “Their bestowals and susceptibilities became one, their purposes one purpose, their desires one desire to such a degree that they sacrificed themselves for each other, forfeiting name, possessions and comfort. Their fellowship became indissoluble.”

Howard Colby Ives soon left the ministry. He spent the rest of his life teaching Americans about Bahá’u’lláh. In 1920, he married Mabel Rice-Wray. They answered an advertisement for traveling salespeople so they could set out across America, sold off all their possessions, and lived out of trunks and suitcases until their dying day.