THE CAKE COLLAPSED IN the oven the first time, so they gathered around the second cake. Sixty-eight candles stuck out of its moist surface. Three flags decorated it: an American flag, a Persian flag, and a British flag. “It was the wish of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá to have a flag of every country on the cake,” the Boston Herald wrote, “as he is universal, and considers every country his own, but there was not room for all.” ‘Abdu’l-Bahá lit the first candle, and then asked the guests to take turns lighting the rest. It was his birthday.

On his second day in Boston, a hundred guests had gathered to celebrate at the home of Alice Breed. But ‘Abdu’l-Bahá left the party early. He never celebrated his birthday because, on the day he was born, something else had also happened, which he considered to be far more important.

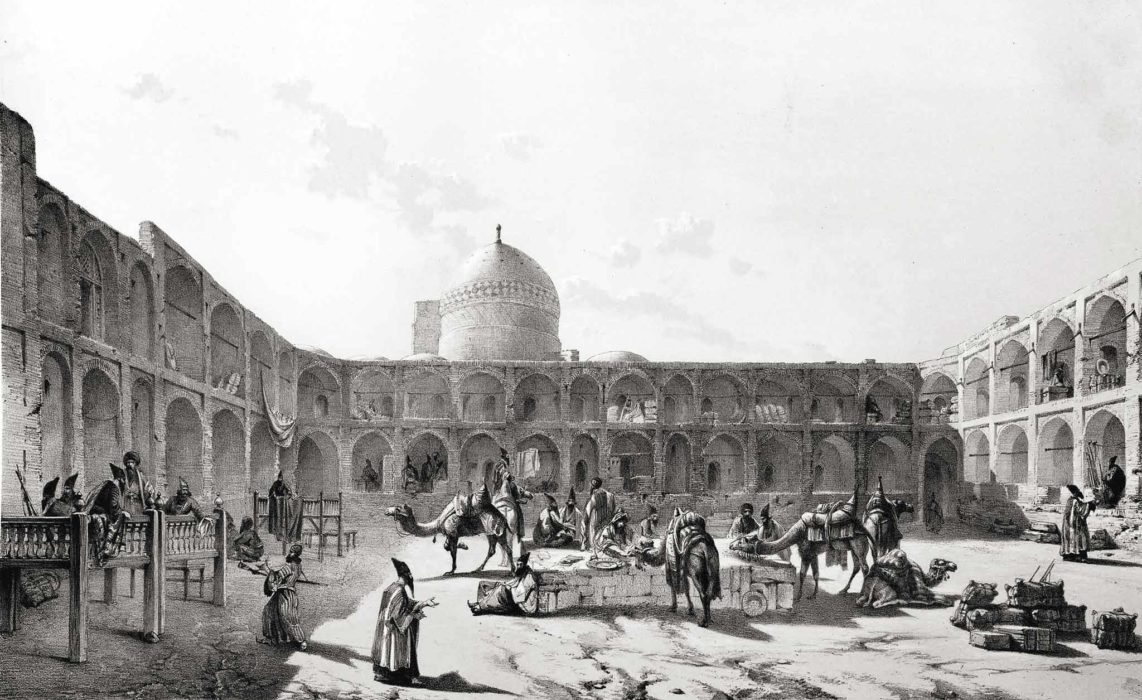

‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s mother, Asiyih, gave birth to him in Tehran. But early that morning in Shiraz, a city 440 miles due south, a young man who called himself the “Báb,” meaning “The Gate,” had set in motion Persia’s greatest upheaval of the nineteenth century, by declaring himself a messenger of God. Within nine years, mobs throughout the country, instigated by religious leaders and aided by the Persian military, had slaughtered 20,000 of his followers and had executed the Báb by firing squad.

Among them was a woman named Táhirih. Three days earlier, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá had spoken to an audience of suffragists at the Metropolitan Temple in New York. What few of them knew was that, when he was just three of four years old, he used to sit on Táhirih’s lap in his father’s house in Tehran.

Táhirih accepted the teachings of the Báb in her twenties, to the consternation of her father and her husband, and became one his most fearless and brilliant advocates. She was a poet, renowned for her learning and her skill in argument. At a conference near the village of Badasht, in 1848, she shocked her fellow believers by appearing before the all-male gathering without a veil. One of them felt so scandalized that he slit his own throat.

By imposing this new image of equality on the Bábís, Táhirih forced them to make a critical break with the past.

On her way back to Tehran she was arrested, sent to the capital, and brought before the king, Násiri’d-Din Sháh. If she would only renounce the Báb and return to Islam, His Imperial Majesty told her, he would make her his bride. She turned him down with a poem:

Kingdom, wealth, and power are for thee,

Beggary, exile, and loss are for me.

If the former is good, it’s thine.

If the latter is hard, it’s mine.

They imprisoned her for four years.

The day before they killed her, the Sháh summoned her again. Again she rebuffed him. They strangled her with a scarf and threw her body down a well. The Times of London reported her death on October 13, 1852. She was thirty-six years old.

Táhirih remained defiant until the end. “You can kill me as soon as you like,” she said, as she faced her murderers, “but you cannot stop the emancipation of women.”

The Tahirih Justice Center, in Washington, DC, works to protect immigrant women and girls seeking justice in the United States from gender-based violence.