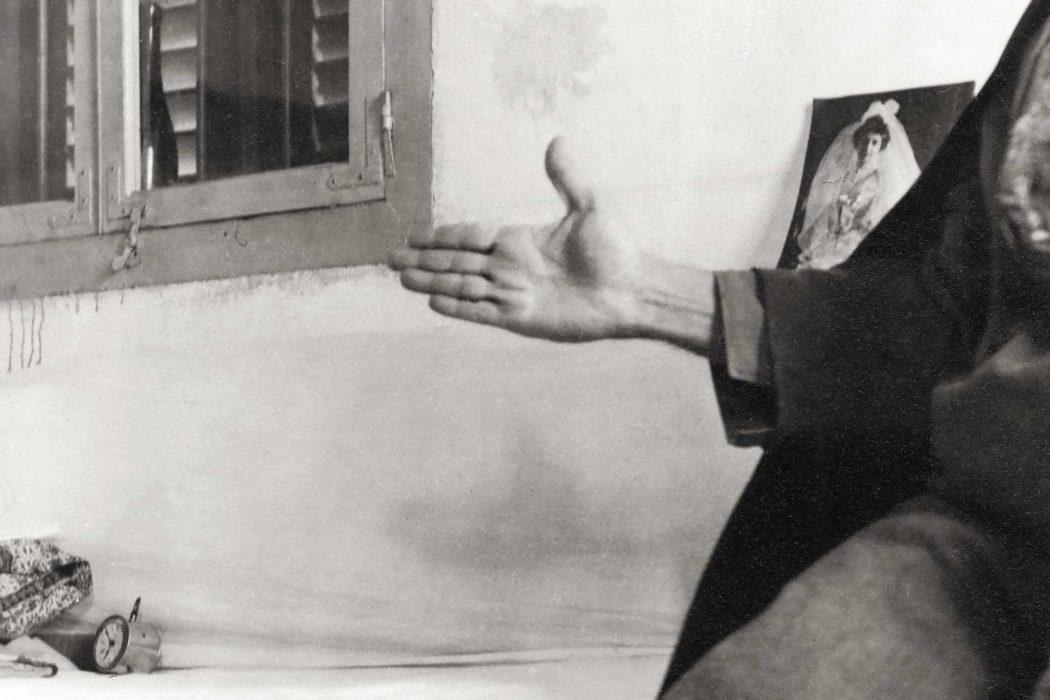

ONE OF THE FIRST recorded images we have of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá shows nothing but his hand. He was reluctant to have his photograph taken, because he didn’t want portraits to circulate and be venerated in an excessive or inappropriate manner. In ‘Akká in 1903, Helen Cole persuaded him otherwise. When she produced her camera, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá reached into the frame with an extended hand and waved. It’s all he gave her.

There are sides to ‘Abdul-Bahá that belie the serious image one may get simply by reading the high-minded talks he gave in America.

He had a quick wit. Earl Redman recounts the story of a man announcing proudly: “O, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, I came 3000 miles to see you.” ‘Abdu’l-Bahá gave a hearty laugh and replied: “I came 8000 miles to see you.” Howard Colby Ives notes that ‘Abdu’l-Bahá often “touched His fez so that it stood at what I called the humorous angle.”

Many afternoons ‘Abdu’l-Bahá went for a stroll in Riverside Park on the Hudson River. He explained: “When I sleep on the grass, I obtain relief from exhaustion . . . .” Seeing him at a small gathering in Cleveland, a reporter noted: “There was no churchy pomp in his manner.” He was also known to get up early to bake bread, and held dinner parties for which he acted as both chef and host.

Then there were cars. Agnes Parsons recounts the story of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá spotting an electric motor car across a busy street in Washington, and sending Mason Remey over with the directive “find out price.” Similar enthusiasm was directed at trains and trams, though ‘Abdu’l-Bahá had less affection for sea travel: the rollicking waves he experienced on the Cedric made his stomach queasy.

Yet lest this convey the impression of a man of leisure, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá slept no more than four or five hours each night. Howard Colby Ives recalls: “From five o’clock in the morning frequently until long after midnight He was actively engaged in service . . . .” Beyond ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s busy schedule of public talks and private meetings, he was also directing the affairs of an international community. During his 7 a.m. breakfast and 10 p.m. dinner each day he responded to a perpetual stream of letters and cablegrams.

Then there were the children. On April 19 in New York, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá was heading to the Bowery Mission when a group of boys saw him and his Persian entourage and began to throw sticks. Carrie Kinney explained to them that ‘Abdu’l-Bahá was a holy man who was on his way to speak to the poor, and they decided they wanted to join him. Instead, arrangements were made for them to visit ‘Abdu’l-Bahá.

When the day arrived, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá stood at the door of the Kinney’s home and greeted each boy as he entered. Howard Colby Ives tells the story of what happened next: “Among the last to enter the room was a colored lad of about thirteen years. He was quite dark and, being the only boy of his race among them, he evidently feared that he might not be welcome.”

“When ‘Abdu’l-Bahá saw him,” Ives wrote, “His face lighted up with a heavenly smile. He raised His hand with a gesture of princely welcome and exclaimed in a loud voice so that none could fail to hear; that here was a black rose.”

“The room fell into instant silence. The black face became illumined with a happiness and love hardly of this world. The other boys looked at him with new eyes. I venture to say that he had been called a black — many things, but never before a black rose.”

Of his time with ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Reverend Ives noted: “Life has never been quite the same since.”