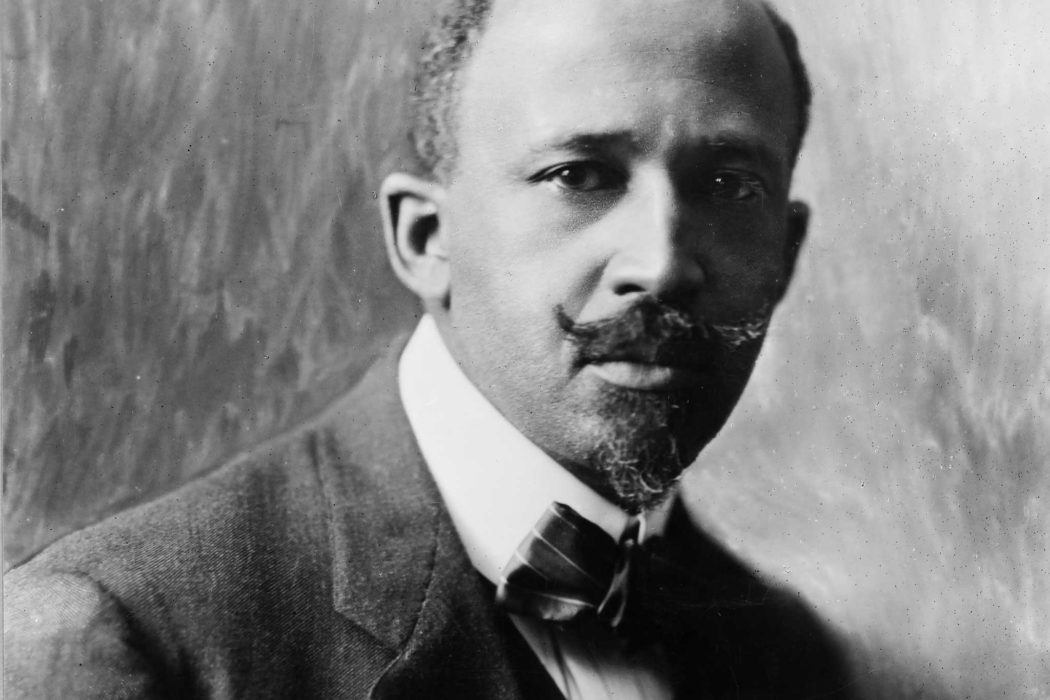

“THERE ARE IN THE United States 26,999,151 males of voting age,” the story went. “Nine and one-tenth per cent of these are of Negro descent.” W. E. B. Du Bois, the editor of The Crisis, the official publication of the NAACP, opened each monthly issue with a section called “Along The Color Line,” a collection of short news items from across the nation that told of the upliftment of African Americans.

“An anti-Roosevelt meeting has been held by the colored citizens of Boston,” read an item in the June, 1912, issue. Another reported that “The late Benjamin Guggenheim, who went down with the ‘Titanic,’ left a bequest of $5,000 to the Colored Orphan Asylum, New York City.” Of the 100,000 people recently made homeless by the flood in New Orleans, it also said, 90,000 of them were black.

But the main story in Du Bois’s magazine in June was the coverage of the Fourth Annual Conference of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, which had taken place April 28–30, in Chicago. It was, he wrote, “one of the most significant meetings ever held in the defense of the rights of colored Americans.”

“Many striking personalities were seen and felt in the gatherings,” Du Bois wrote, “first of all Jane Addams — calm, sweet and so absolutely fearless when she sees the right.” The diversity of the closing session, on the last evening, especially impressed him. It was, he said, “a scene which one would travel far to see.” Not only did a Jewish rabbi preside, but three dynamic speakers shared the stage: a Southern white man, the head of a colored settlement, and “a cultivated colored woman who in quiet tones told of the dynamiting of her own home.”

“As opening and climax to this remarkable gathering came a speech of Abdul Baha and a farewell from Julius Rosenwald. Small wonder that a thousand disappointed people were unable to get even standing room in the hall.”

Of the dozens of speeches given at the conference, Du Bois chose to print just three. One of them was by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá. He had spoken for about fifteen minutes in front of the crowd jammed into Handel Hall at 40 Randolph Street in the Loop area of downtown. He had begun by quoting the Old Testament: “Let us make man in our image, after our likeness.” “Let us find out,” he proposed, “just where and how he is the image and likeness of the Lord, and what is the standard or criterion whereby he can be measured.”

Then he had reeled off a series of rhetorical questions to reveal the incoherence of color-based definitions of what it means to be human: “[C]an we apply a color test as a criterion, and say such and such an one is colored a certain hue and he is therefore, in the image of God? Can we say, for example, that a man who is green in hue is an image of God?”

“Hence we come to the conclusion that colors are of no importance. Colors are accidental in nature. . . . Let him be blue in color, or white, or green, or brown, that matters not! Man is not to be pronounced man simply because of bodily attributes. Man is to be judged according to his intelligence and spirit.”

“That is the image of God.”