“THERE IS NO DOUBT, among thinking people, that this man represents, in great degree, the growing and evolving spirit of our times.” That was Elbert Hubbard in “A Modern Prophet,” an article he wrote about ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in the July 22, 1912, issue of Hearst’s Magazine.

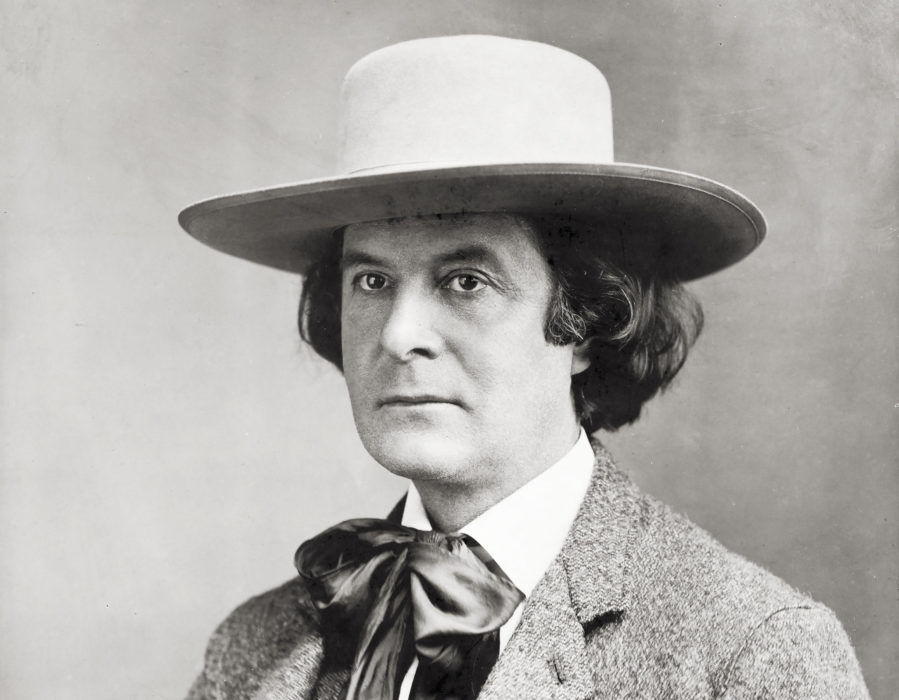

Elbert Hubbard was a businessman turned marketing guru who, after climbing to the highest ranks of the Larkin Soap Company before the age of thirty, decided he was spiritually empty. He moved to East Aurora, a country town south of Buffalo, and established an Arts and Crafts community called Roycroft. The movement was in protest to the industrial revolution, he said, which was rendering handcrafted goods obsolete. Roycroft soon became a site for the meetings of socialists, freethinkers, and suffragists.

Hubbard also developed a second career as a populist writer, using his skills as an ad man to repackage ideas from philosophers and poets into mass market slogans. “Conformists die, heretics live forever,” was one such slogan. He also wrote popular essays with titles like “Jesus Was An Anarchist.” And in 1899 a short story about worker obedience catapulted him into the realm of celebrity.

“According to Abdul Baha,” Hubbard wrote in Hearst’s Magazine, “we are now living in a period of time that marks the beginning of the millennium – a thousand years of peace, happiness and prosperity.” He told his readers that ‘Abdu’l-Bahá had come to the West with a mission, and that no one should doubt his sincerity. “He is no mere eccentric,” Hubbard added.

Elbert Hubbard likely never met ‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Whatever means he used to research his article, he managed to simultaneously capture the spirit of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s message while getting most of his facts wrong. “He speaks many languages and certainly speaks English better than most Americans do,” Hubbard wrote. Of course, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá barely spoke a word of English. Hubbard also claimed that one-third of all Persians had joined the Bahá’í religion.

Hubbard’s article was designed to cater to a country disillusioned with the status quo. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s message, he stated, “presages a world-wide up-springing of vital religion.” “In the world of economics, we in America are infinitely beyond anything that can come to us from the Orient,” Hubbard wrote. “But the divine fire of this man’s spirituality is bound to illuminate the dark corners of our imaginations and open up to us a spiritual realm which we would do well to go in and possess.”

By 1912 handcrafted goods and the bungalows that housed them were going out of style. Hubbard’s marriage ended in divorce when a longtime affair with Alice Moore was exposed. Then the war broke out. “Who lifted the lid off of hell?” Hubbard said. He blamed it all on big business.

On May 1, 1915, Elbert Hubbard and wife Alice boarded the Lusitania bound for Europe. He hoped to interview Kaiser Wilhelm. Hubbard had once written a moving tribute about the Titanic, and the death of a couple who had refused the lifeboats in order to die together. At ten minutes past two in the afternoon on May 7, a torpedo from a German u-boat glided across the water toward the Lusitania. Hubbard and Alice linked arms, entered a room on the top deck, and closed the door.