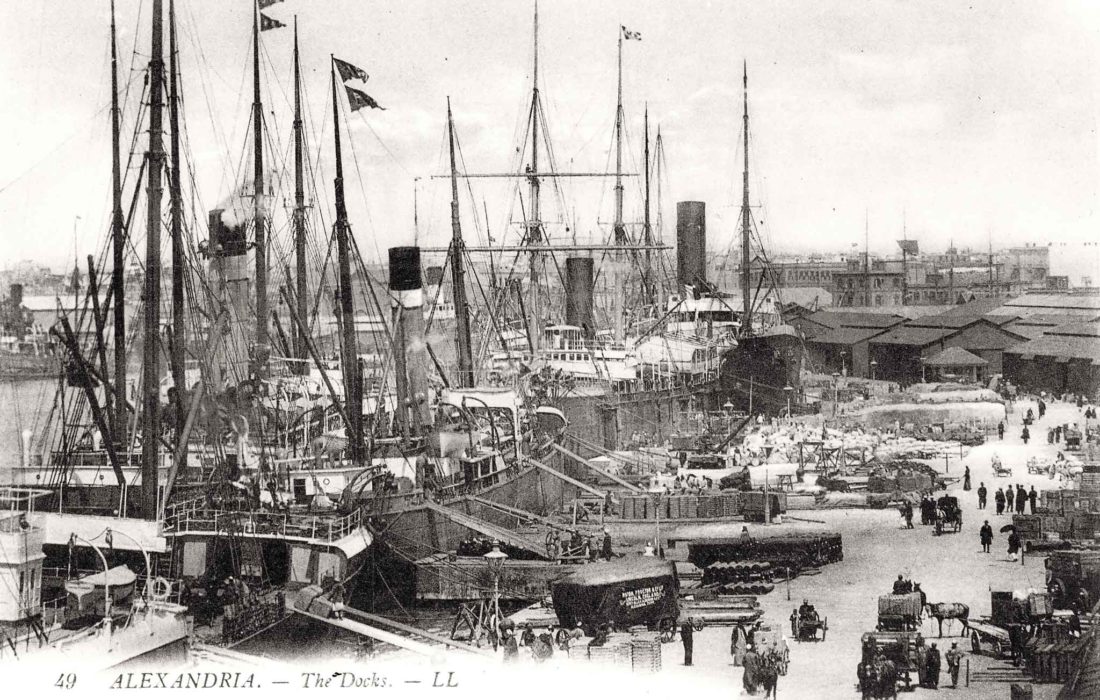

LOUIS GREGORY INHALED THE sea air as his ship broke from the shore. He was leaving America, crossing the same throes of the Atlantic his African ancestors had — but Louis Gregory was unchained. It was March 25, 1911, and he was on his way to Alexandria, Egypt, to meet ‘Abdu’l-Bahá. It was here, in the middle of the ocean, Gregory later said, that he finally felt truly “American.”

Louis’s grandfather had been murdered before he was born. He was a blacksmith who had prospered after the Civil War. He bought a mule and a horse and for this was targeted by the Ku Klux Klan, who drove up to his house one night, called him out, and shot him.

The years between the end of the Civil War and 1877 were the era of Reconstruction. Congress, aided by the Union Army, disbanded the Confederate governments of Southern states and implemented the Fourteenth Amendment, which guaranteed due process and equal protection of the laws to all Americans. The Fifteenth Amendment spurred new elections in which newly freed slaves could vote. Reconstruction also led to the improvement of educational opportunities for African Americans.

Louis’s mother was freed from slavery when she was fourteen. She managed to go to school for a few years before giving birth to two sons: Louis was born on June 6, 1874. But at around the age of five Louis Gregory’s father died of tuberculosis. His mother struggled to support them, but Louis’s grandmother sustained their spirits, bringing dignity, courage, and a love of laughter to the family.

The Compromise of 1877 ended Reconstruction. In a political deal, Rutherford B. Hayes, a Republican, was elected President in return for removing Federal troops from the South. Without the troops to enforce them, the racial legal reforms ceased to function. Throughout the South “Jim Crow” laws at the state level entrenched segregation as a way of life.

The Progressive Era wasn’t very “progressive” for African Americans either. It had begun on a sour note. In 1896, the United States Supreme Court upheld the legal basis of racial segregation under the formula of “separate, but equal.” “Legislation is powerless to eradicate racial instincts or to abolish distinctions based upon physical differences,” they wrote in Plessy v. Ferguson. “If one race be inferior to the other socially, the Constitution of the United States cannot put them upon the same plane.”

In the North, educated black men pushed forward. After graduating from Howard University, Louis Gregory opened a law office in Washington, DC, in 1902. In 1906 he took a position with the Treasury Department. In 1911 he boarded the ship to visit ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in Egypt. As Louis Gregory interacted with the other passengers on board, his biographer Gayle Morrison wrote, “he concluded that blacks had made a unique adaptation to America precisely because their ties with Africa had been so ruthlessly cut. . . .” His fellow travelers, who came from all parts of the world, read his nationality on sight, simply calling him “The American.”

By 1912 little had improved for African Americans on the political front. None of the political parties seemed willing to risk losing the Presidency by upholding the rights of Southern blacks. The Democrats remained the party of segregation. Not much progress had been made under the Republican administrations of Presidents McKinley, Roosevelt, or Taft. While the Socialists upheld black political rights in theory, currents of prejudice ran through the rhetoric of many leading Socialist figures. And then just yesterday, on August 1, 1912, African-American delegates from the South learned that they would not be admitted to the Progressive Party’s upcoming convention. In order to secure Southern votes the Progressives needed a Southern party that was “lily-white,” not one that threatened whites with racial integration.

Shortly after arriving in Alexandria, Louis Gregory met ‘Abdu’l-Bahá. “If it be possible, gather together these two races, black and white, into one assembly,” ‘Abdu’l-Bahá told him, “and put such love into their hearts that they shall not only unite but even intermarry.” ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s solution to the American race problem seemed to be far more fundamental than the political deals that had been struck — and had failed — since Reconstruction.

In tomorrow’s feature, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá makes a surprising announcement to a group of African Americans in Dublin.

In previous features we have examined ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s discourse on race in America. You can find them here:

Day 12: Even Though the World Should Go to Smash

Day 13: This Shining Colored Man

Day 14: Breaking the Color Line

Day 20: The Fallout from a City in Flames

Day 26: The Ultimate Taboo

and Day 62: Along the Color Line.