‘ABDU’L-BAHÁ STEPPED DOWN onto the platform at LaSalle Street Station in Chicago just after 8 p.m. on Friday, September 12, 1912. He knew this part of the city well. Seven blocks north of here he had addressed the Federation of Women’s Clubs at the Hotel LaSalle on May 2. Eleven blocks up he had spoken to a standing-room-only crowd at the Fourth Annual Conference of the NAACP in Handel Hall.

The crowd of well-wishers on the platform parted into two lines to make way for ‘Abdu’l-Bahá. “Come down Zacchaeus,” he called out, “for this day I would sup with thee.” Those who were close enough to hear him turned their attention to a skinny Japanese man dangling above their heads. In the Gospel of Luke, Jesus had singled out Zacchaeus, who had climbed the branches of a tree in order to catch a glimpse of him. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá addressed Saichiro Fujita in the same words; Fujita was hanging from a lamp post.

Saichiro Fujita was born in 1886 in Yanai, on the southwestern tip of the large island of Honshu, Japan, thirty miles southwest of Hiroshima. He arrived in Oakland, California, in 1904, to attend school, met some of the city’s Bahá’ís, and soon embraced the religion. Having missed ‘Abdu’l-Bahá on his swing through Cleveland in May, 1912, where Fujita then lived, he made sure that when ‘Abdu’l-Bahá came back to the Midwest in September he had the best vantage point possible.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá waved Fujita down. Then, as he had done with Louis Gregory in Washington and Fred Mortensen in Malden, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá kept Fujita by his side throughout his stay in the city. When he left for San Francisco, he asked Fujita to come along. Few of the people who saw the two men together knew that they had corresponded since 1906. Fujita had asked if he could come to Palestine to work for ‘Abdu’l-Bahá. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá encouraged him to stay in school instead.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá later arranged for Fujita to live in the home of Mrs. Corinne True in Chicago for the next seven years. When the Great War ended, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá finally invited him to come to Haifa.

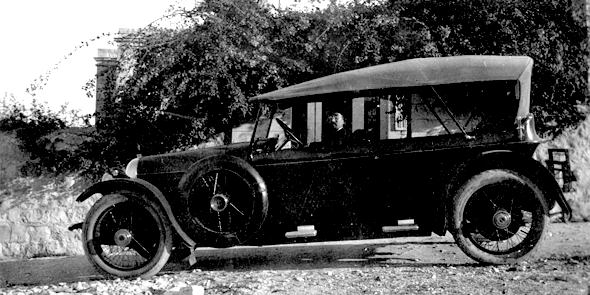

Saichiro Fujita came bearing gifts, or at least escorting one. He arrived with ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s automobile, a gift from an American friend. In a 1965 interview, Fujita recalled that the day he first arrived in Palestine. He met ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s sister, Bahiyyíh, was told that he was now part of the family, and that he should make himself at home. He did: Fujita would be buried in Haifa fifty-seven years later, at the age of ninety.

The two men ate breakfast and lunch together almost every day. They developed a routine of practical jokes, including one where ‘Abdu’l-Bahá challenged Fujita to grow a beard like his, then pulled on it every day when it proved Fujita could only generate the merest collection of hairs. Fujita hid ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s cat in retaliation, and it went on from there.

Having stayed in school paid off for Fujita in the ensuing decades. He planted many of the gardens that would eventually cover the Bahá’í properties in and around Haifa; he helped install electrical fixtures in the many buildings. But in the short term ‘Abdu’l-Bahá took advantage of Fujita’s unassuming nature and endearing sense of humor by having him host the pilgrims who came in ever greater numbers once the war was over.

“‘Abdu’l-Bahá was very, very kind to me,” Fujita recalled in 1965. “We had many trips, many jokes.” When asked what he did for ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Fujita replied: “I never felt that I could do very much for ‘Abdu’l-Bahá.” Then, after a pause, he added: “Sometimes I made him laugh.”