KATE CAREW, AS SHE was called, stepped through the main entrance, minded the seals in the lobby fountain, and made her way to the front desk. “Well, of all the places to find the Master,” she said to herself. Then she noticed how soft and squashy the carpets were. “Of course it’s the carpets. They must seem awfully nice to feet that have trod prison stones. I don’t blame him.”

“Fifth floor, room 111,” the clerk told her, and she repeated it to the elevator man. He pulled the gates closed and they began to rise through the floors of the Hotel Ansonia. “On my way to the more rarefied atmosphere of the upper floors,” she wrote, “I found myself hoping the Baha would tell me I had a lovely soul. They say he finds out the strangest things about you.”

Kate Carew — that was her pen name — was a special kind of journalist, a caricaturist in fact, who used to sketch celebrities while she interviewed them. Every week the New-York Tribune printed her latest interview with the rich and famous, complete with sketches and suffused throughout with her pithy observations and trademark wit. She was Barbara Walters with a sketchbook. Now, at about 6 p.m. on April 19, 1912, she had tucked her sketchbook under her arm and was flitting down the hotel corridor to meet ‘Abdu’l-Bahá.

“I felt all sorts of mystic possibilities awaited me the other side of the door,” she wrote. “I stripped my mind of all its worldly debris . . . I closed my eyes. I attained the holy calm.”

“At my finger’s pressure on the bell the door flew open with a most unholy speed. No fumes of incense, no tinkling of bells, no prostrate figures and whispered benedictions . . . I had been criticizing the lack of simplicity and when I saw it I wasn’t satisfied.”

“Isn’t that the woman of it?”

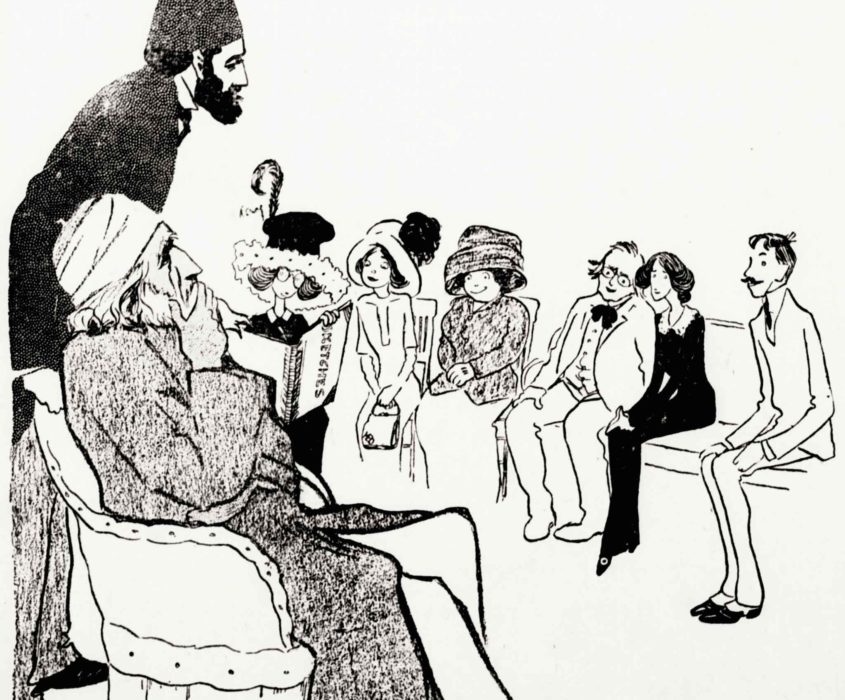

She took a seat in the large reception room. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá was out, so she turned her colorful eye to the curious bunch of people waiting with her, and described some of them in her article: “An enthusiastic, plump, middle-aged little person, gowned in a very worldly manner, haloed with a new spring hat, whose artificial aigrettes had the real optimistic slant.” A pretty girl on a narrow seat: “You felt that she must have lots of oversoul. She wore a sad, withdrawn look as of one who lives on the heights.”

Finally a new pattern of notes joined the room’s chatter, including a “nasal monotone unlike any sound I had ever heard.” The room went silent. “I blinked my eyes. Everybody in the room was standing, breathlessly expectant. I rose mechanically.”

‘Abdu’l-Bahá entered. “He is scarcely above medium height,” Carew wrote, “but so extraordinary is the dignity of his majestic carriage that he seemed more than the average stature.” Within a few minutes her private interview with ‘Abdu’l-Bahá began in an adjoining room.

“Do you think our luxury degenerate,” she asked, “as in this great hotel?”

“Luxury has a limit,” he replied. “Beyond that limit it is not commendable. There is such a thing as moderation.” ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, it turned out, hadn’t picked the opulent Ansonia as his place of residence; it had been booked by friends in New York before he arrived.

“Does the attention paid at present in this country to material things sadden you? Does it argue to you a lack of progress?”

“Your material civilization is very wonderful,” ‘Abdu’l-Bahá answered. “If only you will allow divine idealism to keep pace with it there is great hope for general progress.”

Carew had heard that ‘Abdu’l-Bahá had brought up his four daughters in a liberal household, with Western standards of education: “Do you believe in woman’s desire for freedom?”

‘Abdu’l-Bahá raised his hand to his forehead and touched his turban, adjusting it slightly. “The soul has no sex,” he said.

Carew called to mind last Monday’s news: “In a supreme moment,” she asked, “as in that of the Titanic disaster, should both sexes share the danger equally?”

“Women are more delicate than men,” ‘Abdu’l-Bahá replied. “This delicacy men should take into consideration. . . .” “If the time ever comes when the average woman is a man’s equal in physical strength there will be no need for this consideration; but not until then.”

After a few more questions, she noted that the exhausting day had started to weigh upon ‘Abdu’l-Bahá. His eyelids trembled and he began to adjust his turban and stroke his beard more often. “Shall I go now?” she asked. Fareed, the interpreter, answered: “He has been giving of himself since 7 o’clock this morning. I am a perfect physical wreck, but he is willing to go on indefinitely.”

‘Abdu’l-Bahá opened his eyes again: “I am going to the poor in the Bowery now,” he told her. “I love them.” He invited Kate Carew to come along.

“Can you picture your Aunt Kate and Abdul Baha going to it, hand in hand, through the Ansonia corridors? Perhaps the guests didn’t gurgle and gasp! Perhaps!” “I did feel rather conspicuous,” she writes, “but I braced myself with the thought of the universal brotherhood and really got along fairly well.”

“There was another gasp of surprise at the Bowery Mission as, still hand in hand—he just wouldn’t let me go—the Baha and I trotted through a lane composed of several score of the society’s members. A few of the young ladies had their arms filled with flowers, which afterward filled the automobile. Some four hundred men were present, belonging to the mission.”

‘Abdu’l-Bahá spoke to the homeless men for about twenty minutes. Jesus Christ was also homeless, he told them. “You are His comrades, for He outwardly was poor, not rich. Even this earth’s happiness does not depend upon wealth.”

“You will find many of the wealthy exposed to dangers and troubled by difficulties, and in their last moments upon the bed of death there remains the regret that they must be separated from that to which their hearts are so attached.”

“Therefore,” he said, “we will thank God that we have been so blessed with real riches. In conclusion, I ask you to accept ‘Abdu’l-Bahá as your servant.”

Then Aunt Kate saw something she didn’t expect.

“Just before the services were concluded I saw the courier stealthily approach the platform and hand the Baha a green baize bag. Of course, I wasn’t going to let that go on without finding out all about it, and to my whispered inquiry the Baha said, smilingly:

“Some little lucky bits I am going to distribute to the men.”

“What you don’t expect! I had the surprise of my life! For what do you suppose those lucky bits were?”

“Silver quarters, two hundred dollars’ worth of them!”

“There! Guess you didn’t expect it either.”

“Think of it! Some one actually coming to America and distributing money. Not here with the avowed or unavowed intention of taking it away. It seems incredible.”

“Possibly I may be a bit tired of mere words, dealing in them the way I do, but that demonstration of Abdul Baha’s creed did more to convince me of the absolute sincerity of the man than anything else that had happened.”

“The Master stood, his eyes always turned away from the man facing him, far down the line, four or five beyond his vis-à-vis, so that when a particularly desperate looking specimen came along he was all ready for him, and, instead of one quarter, two were quickly pressed into the calloused palm.”

“I had said good night on the platform, so my last view of Abdul Baha was as he stood at the head of the Bowery Mission line, a dozen or more derelicts before him, giving to each a bit of silver and a word of advice.”

“And as I went out into the starlight night I murmured the phrase of an Oriental admirer who had described him as

“The Breeze of God.”

The Bowery Mission has served homeless and hungry New Yorkers since 1879. If you’re interested in helping them out: https://www.bowery.org/donate/