“THE PEOPLE OF THIS world are thinking of warfare,” ‘Abdu’l-Bahá told an audience in Denver, Colorado, on September 24, 1912, “you must be peacemakers.” Two days earlier, in Omaha, Nebraska, news reached ‘Abdu’l-Bahá of the impending conflict in the Balkan Peninsula. By the time he arrived in Colorado, the front pages of every newspaper in the country were trumpeting that the tensions in the Balkans were about to escalate.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá had lamented Italy’s invasion of Tripoli on April 12, 1912, his second day in America. In 1911, Italian troops had landed on the shores of the Ottoman provinces of Tripolitania and Cyrenaica, in what is now western Libya. Italy’s victory emboldened the Balkan states in their own military aspirations against the Muslims. During the summer months of 1912, the Christian Balkan states -— Serbia, Greece, Montenegro, and Bulgaria -— created the Balkan League, whose mandate was to rid the area of the Ottomans.

On September 22, in Omaha, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá had described how a general European war could be averted. North and South American republics should put pressure on European nations, financiers should refuse to give military loans, railroads should refuse to transport arms. When he arrived in Denver on September 24, he raised the issue of war and peace immediately.

“We are living in a century of light,” ‘Abdu’l-Bahá told his first Denver audience at the home of Mrs. Sidney E. Roberts at 1751 Sherman Street in downtown Denver. But, he said, “Observe how darkness has overspread the world. In every corner of the earth there is strife, discord and warfare of some kind.”

‘Abdu’l-Bahá appears to have taken for granted that the audience at Mrs. Roberts’s knew of Bahá’u’lláh’s teachings on the responsibilities of peace. “A man may be a Bahá’í in name only,” he said. “If he is a Bahá’í in reality, his deeds and actions will be decisive proofs of it.” Accounts refer to a gathering so large that it extended to the front door. Nona Brooks, the minister of the Divine Science Church in Denver was in attendance, and invited ‘Abdu’l-Bahá to speak to her congregation the following evening.

“Many holy souls in former times longed to witness this century,” ‘Abdu’l-Bahá told Mrs. Roberts’s crowd. He invoked the words of Jesus that “Many are called but few are chosen,” then proceeded to define the nature of being “chosen” not as a position that conferred superior status, but rather as a calling to sacrifice and service. “God has chosen you for the progress and development of humanity,” he said, “for the expression of love toward your fellow creatures and the removal of prejudice; God has chosen you to blend together human hearts and give light to the human world.” In short, he told them, be “occupied with service to all mankind.”

‘Abdu’l-Bahá finished by calling his audience to action: “The nations are self-centered; you must be thoughtful of others rather than yourselves. They are neglectful; you must be mindful. They are asleep; you should be awake and alert.”

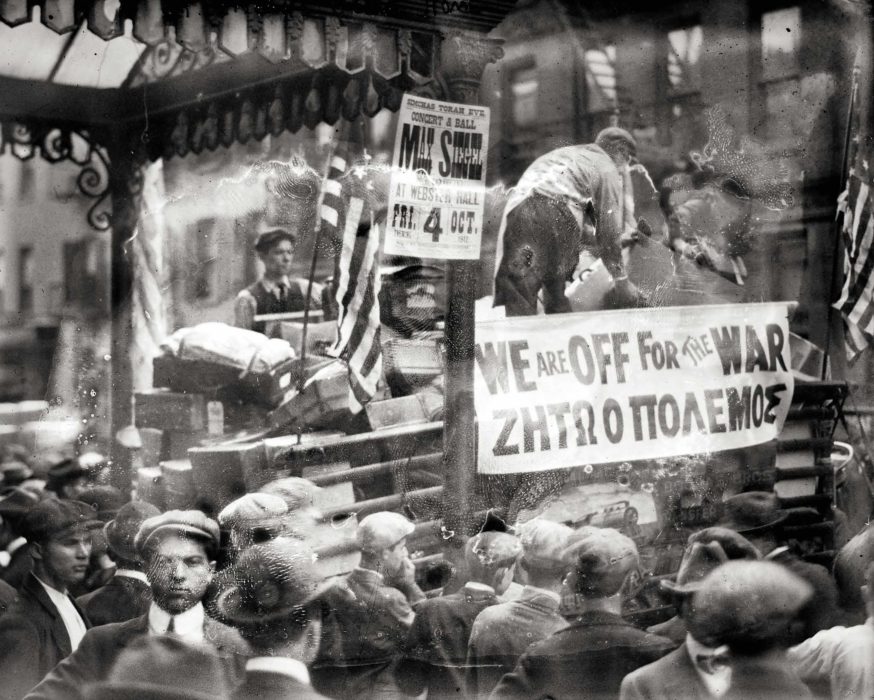

The Balkan War broke out two weeks later. It was short and brutal, lasting just eight months. Most of the Ottoman Empire’s remaining European territories were captured and partitioned among the allies. Only then did the Balkan states turn on each other. On June 16, 1913, Bulgaria, disgruntled over the division of Macedonia, attacked its former allies. The small states that lined the eastern shore of the Adriatic Sea, and clustered among the Balkan mountains, had become a powder keg that would soon bring the rest of Europe to the brink of war.