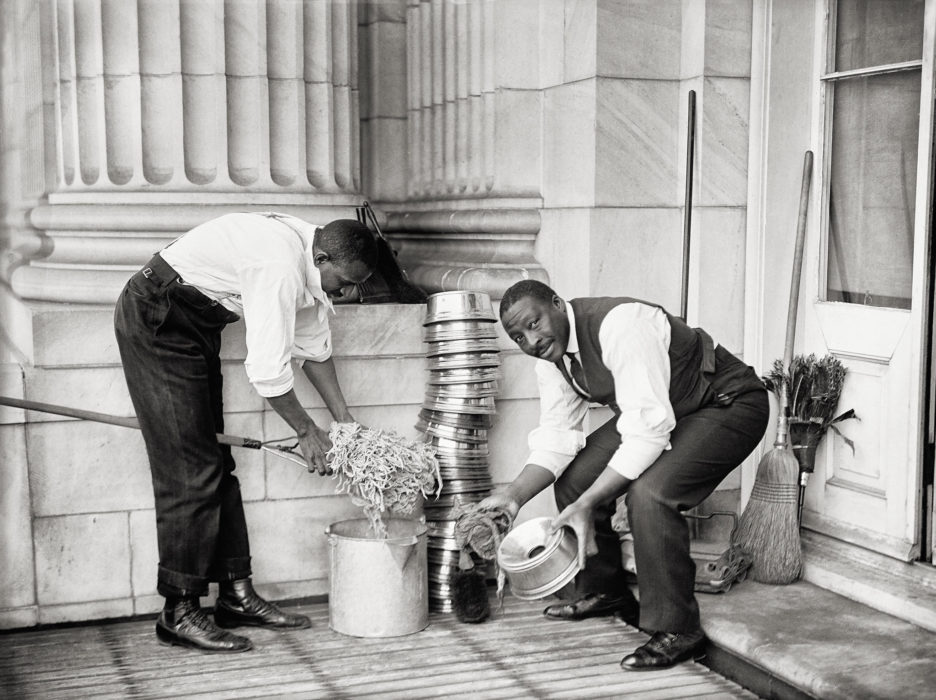

ALMOST COMPLETELY SEPARATED FROM Agnes Parsons’s social world – both psychologically and physically – lived the African American citizens of Washington. In 1912, the world’s second-largest black community called Washington home, having been overtaken in sheer numbers by New York just before 1900. But whereas in New York the African American community was only a drop in a very large bucket, almost one-third of Washington’s inhabitants were black.

Washington was a Southern city, filled to the brim with Southern attitudes about nation, society, culture, and race, many of which were reflected, one way or another, in the group of Bahá’ís that had percolated up among the lettered streets since 1898, when the community had been founded, and 1899, when Phoebe Apperson Hearst had begun holding meetings in her Washington home.

Nothing resembling a unified opinion on race could be found among the capital’s Bahá’ís. By 1912 some of them – the few who were aware of the racial implications of their new religion – were already holding integrated meetings. Thirty years later, one of them reflected on the situation: “Even where all the believers were free from prejudices some felt that it would upset inquirers after the truth if they were confronted too soon with signs of racial equality. . . . On the other hand, others were [insistent] that such principles should be upheld and applied even though the world should go to smash.”

But most Washington Bahá’ís, due to custom, habit, avoidance, or simple lack of knowledge, remained untouched by the issue. Little did they suspect that ‘Abdu’l-Bahá was about to disabuse them of their beliefs about race, and confront them with an entirely new perspective on the meaning of social equality.

Enter Louis George Gregory, a thirty-seven-year-old, Fisk- and Howard-educated African American lawyer from Charleston, South Carolina. As president of the Bethel Literary and Historical Association, the oldest African American organization in Washington, he was one of the most prominent members of the capital’s African American community. He had eagerly followed the developments of W. E. B. Du Bois’s Niagara Movement, and later characterized his own views on the race issue at that time as “radical and wide-eyed,” a “program of fiery agitation in behalf of a people. . . .”

Louis Gregory first learned of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in late 1907 from a colleague – a cultivated, southern white gentleman who shared his office at the Treasury Department. Gregory attended a discussion with Bahá’ís at the old Corcoran building as a favor to him. He was not interested in religion. Earlier in his life he “had been seeking,” he said, “but not finding truth, had given up.”

Yet as he heard more about ‘Abdu’l-Bahá and this new faith, Louis Gregory came to believe he had found the divine reply to the prayer Du Bois had written after the Atlanta Riot, “in the Day of Death, 1906”:

Bewildered we are, and passion-tost, mad with the madness of a mobbed and mocked and murdered people; straining at the armposts of Thy Throne, we raise our shackled hands and charge Thee, God, by the bones of our stolen fathers, by the tears of our dead mothers, by the very blood of Thy crucified Christ: What meaneth this? Tell us the Plan; give us the Sign!

Keep not thou silence, O God!

“Heaven and Earth heard that piercing cry,” wrote Louis Gregory in a 1936 review of Du Bois’s Black Reconstruction, “uttered by one, echoed by millions.” “Earth and Heaven answered.” After investigating the new religion for eighteen months, Louis Gregory became a Bahá’í in June, 1909.

By this time, at least fifteen African Americans had joined the community in the DC area, but ‘Abdu’l-Bahá singled Louis Gregory out. “I hope,” he wrote in response to Gregory’s first letter to ‘Akká in 1909, “that thou mayest become . . . the means whereby the white and colored people shall close their eyes to racial differences and behold the reality of humanity, and that is the universal unity which is the oneness of the kingdom of the human race. . . .”

Then, in the spring of 1911, Louis Gregory visited Ramleh, Egypt, where ‘Abdu’l-Bahá was staying in preparation for his first visit to Europe. During their first conversation ‘Abdu’l-Bahá immediately cut “to the substance of the issue.” “What of the conflict between the white and colored races?” he asked.

“This question made me smile,” Gregory wrote, “for I at once felt that my Inquirer, although He had never in person visited America, yet knew more of conditions than I could ever know. I answered that there was much friction between the races. That those who accepted the Baha’i teachings had hopes of an amicable settlement of racial differences, while others were despondent. Among the friends were earnest souls who wished for a closer unity of races and hoped that He might point out the way to them. He further questioned: ‘Does this refer to the removal of hatreds and antagonisms on the part of one race, or of both races?’ Both races, was my answer, and He said this would be done.”

“Work for unity and harmony between the races,” ‘Abdu’l-Bahá told him. “The colored people must attend all the unity meetings. There must be no distinctions.”