BY ALL ACCOUNTS, THE first thirty-three years of Thornton Chase’s life were a torrent of suffering, heartache, and failure.

He was born James Brown Thornton Chase on February 22, 1847, in Springfield, Massachusetts. His mother, Sarah Thornton Chase, died of complications from childbirth sixteen days later. His father, Jotham Chase, remarried, but his new wife had no affection for the young boy. By the age of thirteen James was in the care of a Baptist minister in nearby Newton. His father and stepmother had started a new family.

James entered the Union Army at the age of sixteen, fought in two battles in the final year of the Civil War, and went deaf in his left ear from a cannon blast. After the war he entered college, only to drop out in his freshman year. Then, at the age of twenty-three, he secured his first taste of happiness.

He was now going by the name “Thornton,” taking his mother’s maiden name as his first. He married a young teacher, Annie Allen, and they bought a home in Springfield. Ten months after the wedding they welcomed their first daughter, naming her Sarah Thornton Chase after Chase’s mother. He started a business dealing in timber.

Within a year, the business went belly up.

With no means to support his family, and few opportunities in Springfield, Thornton sought work in nearby Boston. But there were tens of thousands of other men chasing the same work, and Chase could only find odd jobs. Then Annie was pregnant again and things seemed hopeless.

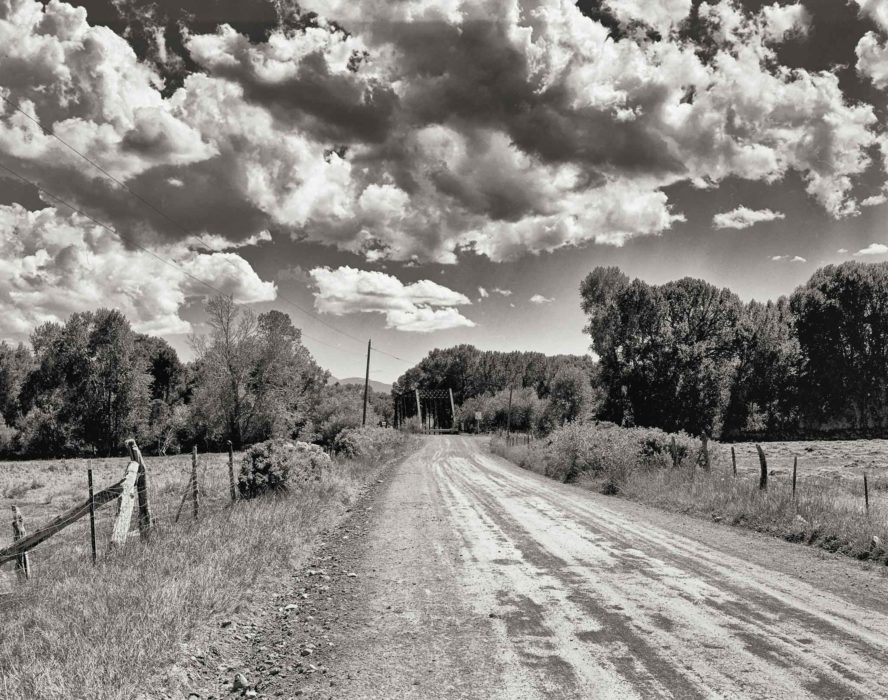

Chase left Annie and the young Sarah in Springfield and headed to the frontier in a desperate search for employment. Over the next five years it led him to Fort Howard, Wisconsin, a logging town on the western shore of Lake Michigan; then south to Chicago, still devastated from the Great Fire; on to White Church, Kansas, a prairie hamlet just outside of Kansas City; then further west to the tiny village of Wabaunesee; and finally to Del Norte, a mining town on the edge of the San Juan Mountains in Colorado. But Chase could barely keep a roof over his head, let alone send money home.

In February 1878, he received notice that Annie had filed for divorce, claiming that Chase had deserted her.

Chase wrote the court in earnest, telling his side of the story, but the judge sided with Annie and dissolved the marriage. Chase turned his back on his old life and ventured into the San Juan Mountains in search of gold and silver. The only account of Chase during these years describes him as “undoubtedly crazy.”

Years earlier, before Chase had left Springfield for the frontier, he had a vision which, he later said, pulled him back from the brink of destruction. It was his refuge during these long and difficult years. “My experience was in the presence of a Man,” he said. “It was the Christ.” He felt “a perfect evanescence, an absolute oneness, the actual ‘Nirvana.’” It was, he wrote, “exhilaration and joy in the midst of grief and pain.” Reflecting back on this moment, he asserted: “It comes to sufferers.”

By 1880 Chase was back from the mountains. Something had changed. At the age of thirty-three he married Eleanor Pervier from Iowa, found work as a journalist, and became a published poet. His verses revealed a strong mystical bent. In his spare time, he began an intensive study of world religions. Chase soon landed a full-time sales job at the Union Mutual Life Insurance Company. Then he and Eleanor had a son.

In 1893, Chase received a major promotion that would provide him with the success and stability that had eluded him his entire life. The company appointed him superintendent of agencies, making him one of its top officers. It would also cause him to relocate to Chicago, where he would discover the teachings of Bahá’u’lláh.

Chase arrived in Chicago the same year the city hosted the World’s Columbian Exposition. Chase either attended the World’s Parliament of Religions or read a transcript of the proceedings, and was deeply moved by Dr. Henry Jessup’s speech, which quoted Bahá’u’lláh. Shortly thereafter he met Ibrahim Kheiralla, a Syrian-born Bahá’í who had traveled to America to pursue business opportunities. Kheiralla gave a class on Biblical prophecies and Chase attended. He even bought a Bible, cut out key prophetic verses, and arranged them on long sheets of paper.

By 1894, at the age of forty-seven, Thornton Chase had found what he was looking for.

In tomorrow’s feature: ‘Abdu’l-Bahá takes a special trip to Los Angeles to pay his respects at Thornton Chase’s gravesite.