‘ABDU’L-BAHÁ’S AUTOMOBILE halted in front of 33 East 36th Street in the early afternoon on Monday, November 18, 1912. His party of six ascended a broad flight of steps between two sleek Assyrian lionesses who kept watch in pink Tennessee marble before the recessed portico of an Italian Renaissance villa in midtown Manhattan.

The architect of the place, Charles Follen McKim of the renowned firm McKim, Mead & White, had suffered a nervous breakdown over this building—or, more precisely, over having to accommodate the insistent demands and fastidious tastes of his client. On other projects McKim might have done as he pleased, but one simply did not say no to J. Pierpont Morgan.

Volcanic. Imperious. Intimidating. The qualities of the man blaze from the photographic portrait Edward Steichen took of him in 1903. Morgan’s ferocious eyes burn from behind his massive nose, which had been swollen and turned purple by a chronic skin disease. His left hand grasps a dagger—or so it appears from the way the light glints off the arm of his chair.

Morgan’s powerful physical presence symbolized his ubiquitous command over the national economy. Like millions of Americans, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá had never been far from Morgan’s mighty reach. He had sailed to New York on a Morgan ship; conversed after dinner beneath the glow of Morgan incandescent lamps; slept in Morgan-operated Pullman cars speeding along Morgan-controlled railroads and across bridges made from Morgan steel; had stories printed about him in the Morgan-financed New York Times; sent telegram messages from Western Union stations bankrolled by Morgan money; and he had joined New Yorkers as they watched the new Woolworth Building rise on Broadway in 1912 to become the tallest building in the world, built by a Morgan civil engineering firm.

The titan of Wall Street had invited ‘Abdu’l-Bahá for a private interview this afternoon here, at his private library. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá entered through heavy bronze doors into the illuminated splendor of a vaulted rotunda. Mosaic panels, and columns of veined skyros and cippoline marble, textured the space and at ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s feet a colorful marble floor unfurled, inlaid with pieces from the Roman Forum and a central disc of deep purple porphyry. The domed ceiling of blue and white stucco bore paintings and reliefs of classical figures that Henry Siddons Mowbray had modeled on Raphael and installed beneath the gentle light of a central oculus. Gazing upward, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá could see murals inspired by Pinturicchio, which adorned lunettes over the main entrance and above doors to the East and West rooms, depicting scenes and legendary lovers from Greek and Roman epics, Arthurian romances, Dante’s Divine Comedy, and Renaissance lyric poetry. Morgan received guests in the West Room, his large, plush study. His son-in-law wrote that no one could really know him who hadn’t seen him sitting quietly in front of the fire; chomping on a big black cigar; playing solitaire beneath the coffered wooden ceiling; enveloped by the bright red damask silk that lined the study’s walls.

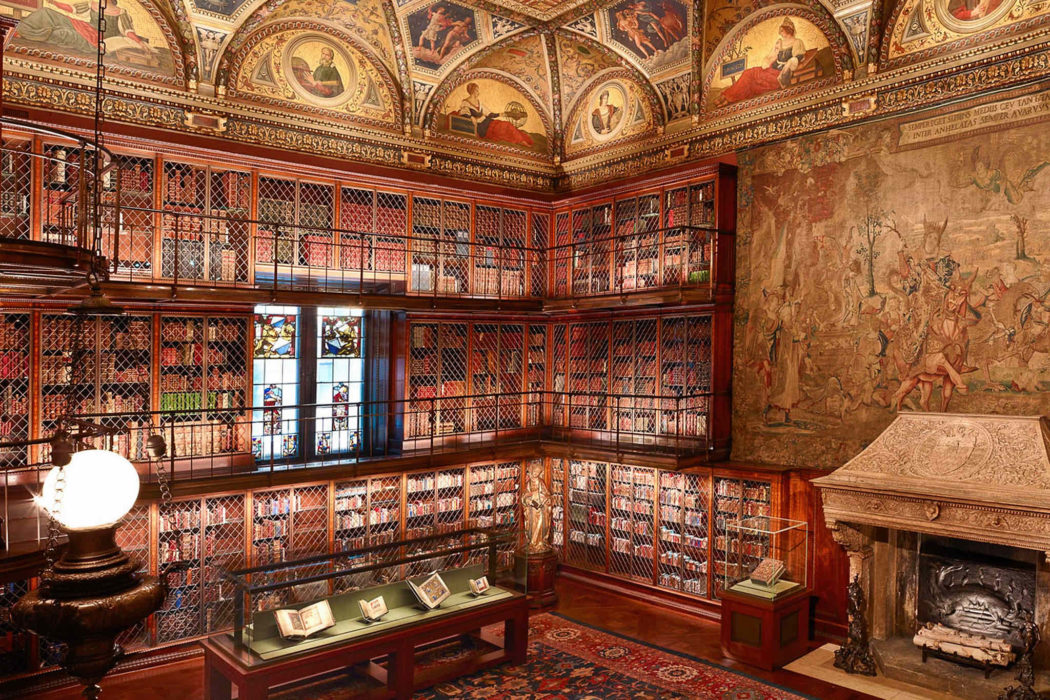

But today he wasn’t there. Some urgent business matter had arisen, and, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá learned, Morgan wouldn’t be able to come. He was directed instead to the East Room, a golden hall thirty feet high, which housed Morgan’s enormous collection of rare books and manuscripts in three tiers of floor-to-ceiling bookcases, made from bronze and rich Circassian walnut. McKim had imported an ornate mantel from Italy for the room, carved from Istrian marble, and above it Morgan hung an old Flemish Renaissance tapestry, which dominated the long eastern wall. It was called “The Triumph of Avarice.”

A few years later, a New England lawyer wrote ‘Abdu’l-Bahá to ask his views on some economic problems—on profit-sharing between employers and workers, and on wealth. “The essence of the Bahai [sic] economic teachings is this,” he replied, “that immense riches far beyond what is necessary should not be accumulated.”

And ‘Abdu’l-Bahá spoke of Morgan:

The well-known Morgan who owned a sum of 300 million and was day and night restless and agitated did not partake of the Divine bestowals save a little broth. . . . He invited me to his library and to his home that I may visit the former and have a dinner at his house. I went to the library in order to look at the oriental books but . . . did not accept his [dinner] invitation. In short, he eagerly desired that I should visit him in the library but meanwhile important financial problems arose which prevented him from being present and thus he was deprived of this bounty. Now had he not such an excessive amount of wealth, he might have been able to present himself.

“This wealth,” ‘Abdu’l-Bahá said, “was for him a vicissitude and not the cause of comfort.”

Morgan’s Sturm und Drang, in fact, concealed an isolated, shy, and quiet man, prone to depression but having an uncompromising sense of integrity. “One nod of the massive head was security for fifty million,” Edmund Morris, Theodore Roosevelt’s biographer, writes. In the era before the Federal Reserve, when the United States had no central bank, J. P. Morgan twice found himself on the hook to rescue the national economy, forced to raise tens of millions of dollars on the spur of the moment and to make decisions that could ruin thousands of lives. During the Panic of 1907, when investors made a run on the Knickerbocker Trust, one of New York’s most reliable old-money banks, Morgan decided enough was enough, and he let it collapse. “I can’t go on being everybody’s goat,” he said.

“I wonder how many other people know, as I do, of the utter loneliness of his life?” Belle da Costa Greene, his librarian, wrote. She knew Morgan perhaps better than anyone:

It seems to me that he is bound to a perpetuity of pain . . . the ever-recurring bitterness of knowing that his kindness, friendship, and rare affection [have] met with a base or at best a poor return. He gives all and gets what? Only a sickening realization of his money and the world-power it brings him.

A member of Morgan’s staff laid out the books and art pieces for ‘Abdu’l-Bahá on the viewing tables. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá spent two hours or more poring over the material. When he was finished, he wrote and signed a short note in Morgan’s guestbook, a prayer for blessings upon the tycoon:

O Thou Generous Lord!

Verily this famous personage has done considerable philanthropy, render him great and dear in Thy Kingdom;—make him happy and joyous in both worlds, confirm him in serving the Oneness of the world of humanity, and submerge him in the sea of Thy favours.

An Associated Press reporter on the scene thought the whole business made a fine little spectacle. They twisted ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s sentiments into a spiffy opening lead, and came up with a catchy headline, which AP dispatched over those same Morgan copper wires the next day.

“Persian Highbrow Dubs Morgan ‘Some Philanthropist,’ ” the headline read. “J. P. Morgan was written down yesterday as one who had done ‘considerable philanthropy’ when his library in East 36th street was visited by Abdul Baha.”