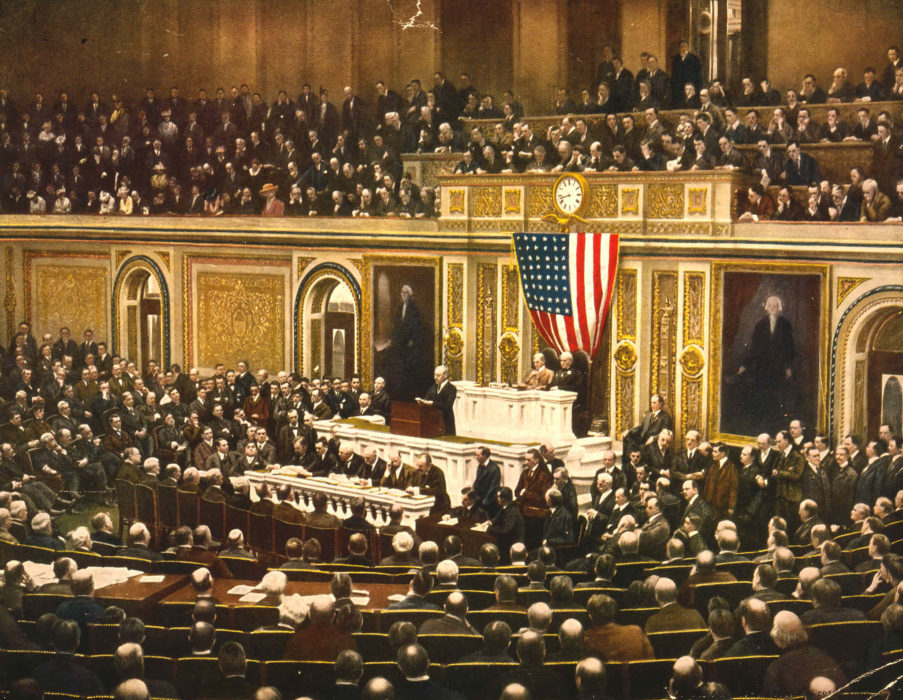

WHEN WOODROW WILSON ASKED Congress to summon the nation to war on April 2, 1917, he shared his fellow Americans’ reluctance to hurl themselves and their children into the ghastly spectacle taking place across the ocean. It was a war between aging empires, after all, monarchies obsessed with national aggrandizement and colonial expansion.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá had praised the American government for being free of the militaristic obsessions of the European powers. He had proposed to the nation a higher spiritual calling – that it use its unique position in the world to lead the nations towards lasting peace. President Wilson tried. He encouraged the warring nations of Europe to negotiate a ceasefire, and offered to mediate peace talks. The war, he believed, directly contradicted every ideal of Progressivism. “Every reform we have won,” he declared, “will be lost if we go into this war.” And so he did everything possible to keep America out.

But the very fact of war would infiltrate the peaceful conscience of his neutral nation and infest it with a sense of looming threat. Campaigns for “preparedness” swept the country after 1914. In 1915, a German u-boat sank the British liner Lusitania, sending 128 Americans to the bottom of the sea. Three months later, even the stoic Wilson voiced alarm that the United States was “honeycombed with German intrigue and infested with German spies.” When the Bolshevik Revolution toppled the imperial Russian government in October, 1917, the fear that a Communist uprising was imminent in America turned into national hysteria. During the “Red Scare,” Americans came to believe that their very way of life was under attack.

America was formally in the war for just eighteen months. In 1917, its industrial productivity exceeded any European nation, but its military was almost non-existent. America quickly recruited an army of four million men, and sent two million overseas. To mobilize the nation, President Wilson created nearly five hundred War Service Committees. A Committee on Public Information, under George Creel, set up a vast propaganda machine to ensure the populace was inspired and loyal, that goods and money kept flowing. Suspect individuals, including conscientious objectors, labor activists, and many immigrant groups, were placed under surveillance. War study courses even made their way into elementary schools.

The nation that had been praised by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá for its liberty and optimism only five years earlier, whose buoyant energy he said was epitomized by its favorite statement — “All right! All right!” — was suddenly fixated on conflict and engulfed in fear. President Wilson’s great dread, that the war would brutalize human nature, was becoming a reality both at home and abroad.

America entered the Second World War just as reluctantly. In 1939, its military was the seventeenth largest in the world, one behind Romania. By 1945, America had dropped two atomic bombs and had emerged as a superpower. The specter of annihilation hung over America and the world in the Cold War that ensued. Preparedness for war became a permanent feature of American life.

President Dwight D. Eisenhower serves as a fitting bookend to Woodrow Wilson and his ambivalence over the militarizing of America. Eisenhower was Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces in Europe during World War II. He ran for President in 1952 advocating a strong military and an activist foreign policy. He shepherded the end of the Korean War, forced Israel, Britain, and France to end their invasion of Egypt during the Suez Crisis, and worked hard to keep a lid on the Soviet-American rivalry. It was a reminder that those who have actually experienced the horrors of war are often the ones most committed to preventing it.

Shortly after his presidency began, the former five-star general found himself giving speeches on peace. “Every gun that is made, every warship launched, every rocket fired signifies, in the final sense, a theft from those who hunger and are not fed, those who are cold and are not clothed,” Eisenhower said in 1953. “This world in arms is not spending money alone. It is spending the sweat of its laborers, the genius of its scientists, the hopes of its children.”

Eisenhower left office in 1961 warning of the growing power of the “military-industrial complex.” The potent term is what most remember from his farewell address, yet he also noted that perpetual preparations for war were at odds with the nation’s history. He cautioned that war was absorbing too large a proportion of national life, with grave ramifications for its spiritual health. He stated that America’s leadership depends “on how we use our power in the interests of world peace and human betterment.”

Eisenhower concluded his farewell address with a prayer for “all the peoples of the world,” that echoes many of the themes that ‘Abdu’l-Bahá spoke about to Americans fifty years earlier. “We pray that peoples of all faiths, all races, all nations, may have their great human needs satisfied, that those now denied opportunity shall come to enjoy it to the full; that all who yearn for freedom may experience its spiritual blessings; that those who have freedom will understand, also, its heavy responsibilities; that all who are insensitive to the needs of others will learn charity; that the scourges of poverty, disease and ignorance will be made to disappear from the earth, and that, in the goodness of time, all peoples will come to live together in a peace guaranteed by the binding force of mutual respect and love.”