THE SMALL GOLDEN TROWEL wasn’t up to the task. The rocky ground at Grosse Point, fourteen miles north of Chicago, could not be breached. Someone scrambled for an axe. At the center of the expectant crowd, about three or four hundred strong, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá waited..

Those who joined him at this groundbreaking ceremony for the new Bahá’í House of Worship came from a diversity of backgrounds one wouldn’t expect to find in Chicago: Indian, African, Persian, French, Japanese, Native American, and more.

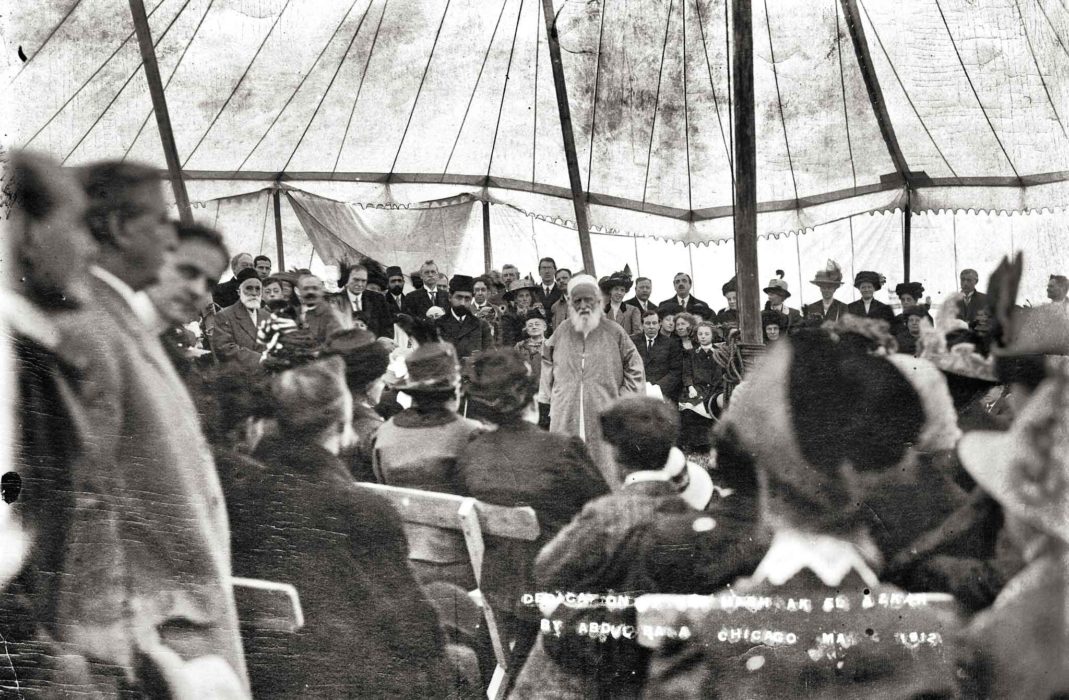

Early this morning, May 1, 1912, they had begun to assemble on this piece of land in the village of Wilmette. The Master had arrived at 1 p.m. First he took a private moment to console Mrs. Corinne True, whose son, Davis, had passed away the night before. Mrs. True had invested more than five years of her life in finding a site for the temple, and in raising the funds necessary to buy the land. Today, in spite of her recent loss, she was here to see things through. Then ‘Abdu’l-Bahá walked under the large tent where three hundred people sat on chairs in concentric circles, between nine equally spaced aisles. He strode to the center and began to talk about this unique religious institution.

Thousands,” he said, “will be built in the East and in the West.” But they were more than just places to pray. They would become the central edifices in a complex of institutions devoted to social, humanitarian, educational, and scientific pursuits. Together, they would offer a new model of faith dedicated to the service of humankind. They would become “one of the most vital institutions in the world.”

The temple’s design, by Louis Bourgeois, a French Canadian architect, spoke to its purpose. Circular, nine-sided, nine doors, a central dome. A skin made of quartz crystals embedded in white Portland cement, as delicate as lace, would cover its iron skeleton. Natural light would illumine it during the day, and at night it would become a beacon along the western shore of Lake Michigan. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá described it as a model of unity: “that all religions, races and sects may come together within its universal shelter; that the proclamation of the oneness of mankind shall go forth from its open courts of holiness.”

Then the crowd walked outside to break ground. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá swung the axe high, then brought it down with purpose, piercing the earth with a thud. Corinne True suggested a woman should go next. Then others took their turns with a shovel, creating a small hole.

A small, crooked limestone block lay next to it. Nettie Tobin had found it discarded at a construction site in the city four years ago and had lugged it fourteen miles to the temple land. She didn’t have anything else to offer. Those in attendance recalled the Book of Matthew, chapter 21, verse 44: “The stone which the builders rejected, the same is become the head of the corner: this is the Lord’s doing, and it is marvelous in our eyes.”

‘Abdu’l-Bahá reached down, scooped up handfuls of earth, and presented them to members of the crowd. Then he pushed the limestone block into the waiting hole, packed soil around it, and pounded the dirt down hard.

“The temple is already built,” he said.