CHARLES DARWIN’S BOOK, On the Origin of Species, was printed in Britain on November 24, 1859, and reached American readers two months later. Theories of evolution had gained currency in the decades prior to the book’s publication, including those that suggested that species might change over time. The theories were controversial, conflicting as they did with the orthodox notion of a hierarchy of creatures operating within a fixed system of divine creation, and the scientific community largely opposed them.

Darwin’s book not only argued in favor of evolution, but put forth a compelling theory for how it operated. It explained that in the struggle for life within natural systems, populations more suited to the environment are more likely to survive, and therefore more likely to reproduce. These populations leave inheritable traits to future generations — a process Darwin called “natural selection” — and over time, the resulting variations accumulate to form new species.

The book generated widespread discussion in scientific, philosophical, and religious circles. Liberal theologians welcomed its challenge, noting that religious ideas cannot remain stagnant. Others declared its hypothesis metaphysically neutral. But gradually, its implications became undeniable. If science could explain the creation of increasingly complex forms of life in purely material terms, then perhaps there was no compelling reason to believe in a Creator.

On the evening of October 10, 1912, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá addressed the Open Forum in San Francisco — a group devoted to the discussion of economic and philosophical ideas — and he tackled the issue of evolution head on. He argued in favor of evolution, albeit with critical differences from the physical mechanics of Darwin’s theory, and he drew an entirely different set of metaphysical conclusions.

In Darwin’s second book on evolutionary theory, The Descent of Man, published in 1871, he drew biological analogies with baboons, dogs, and “savages” to provide evidence for the descent of humans from animals. In San Francisco on October 10, 1912, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá crafted a more precise definition based on what differentiates humans from animals. Among those critical elements, he said, are reason, abstract thought, and scientific advancement. The animal, he argued, is bound by its five senses and lives entirely within the dictates of natural instinct. “All phenomena,” he said, “are captives of nature.”

But man is the exception to this rule. “By defying the laws of nature,” ‘Abdu’l-Bahá argued, “he can soar in the air, or sail over the seas in a ship, or explore the deep in a submarine. He can imprison in an incandescent lamp such a tremendous and powerful force as electricity and convert it to his use.” ‘Abdu’l-Bahá continued with examples of the most remarkable inventions of the age: the phonograph and telephone among them.

“In brief,” he said, “all the arts and sciences, inventions and discoveries now enjoyed by man were once mysteries of nature and should have remained hidden or latent. But through the ideal faculties of man the laws of nature have been defied, and the secrets of nature have been brought out of the invisible into the plane of the visible.”

Yet despite these distinctive characteristics, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá noted that materialist philosophers “endeavor to prove by the human anatomy that man originated from the animal.” ‘Abdu’l-Bahá agreed that humans had undergone biological changes through time. “Let us suppose,” he said, “that the human anatomy was primordially different from its present form . . . that at one time it was similar to a fish, later an invertebrate and finally human.” Yet throughout this progression, he argued, “the development of man was always human in type, and biological in progression (italics added).”

In 1904 in Palestine, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá had described how complex entities develop in response to some questions by Laura Clifford Barney of Washington, DC. “The growth and development of all beings is gradual,” he had told her, “this is the universal divine organization and the natural system.”

‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s talk at the Open Forum was one of the longest and most intricate he delivered during his time in America. But its underlying logic rested on two principles. First, while human beings have developed biologically through many stages of evolution, we were always destined to be human, realizing a latent potential over time. Second, the qualities that distinguish us — reason, abstract thought, scientific advancement, and so on — are not merely minor differentiators, but characteristics that separate us fundamentally from animals.

An additional element in ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s engagement with Darwinian evolution was not covered in his San Francisco talk, but was documented by Ms. Barney during her time in Palestine, and published in the 1908 book Some Answered Questions. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá disagreed with Darwin’s contention that evolution is “blind,” lacking purposeful direction or intent. Instead he argued that the evolutionary scheme was part of a divine plan. The appearance of humans, he said, was the culmination of the process. In fact, creation would be imperfect and incomplete without us.

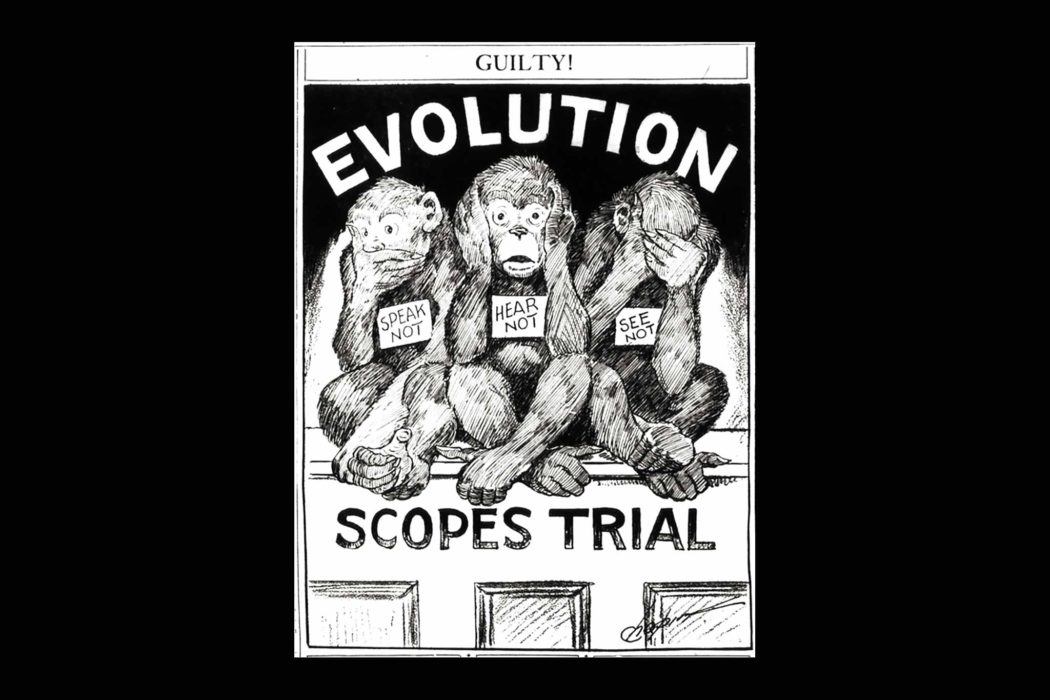

Thirteen years after ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s address to the Open Forum, the debate over evolution in America came to a head during the infamous “Scopes Monkey Trial.” The State of Tennessee had passed a law that made it illegal to teach evolution in state-funded schools. The American Civil Liberties Union financed a test case in which John Scopes, a high school teacher, agreed to violate the law. The nation was transfixed as two legendary figures took up the cause: three-time presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan argued for the prosecution; eminent defense attorney Clarence Darrow defended Scopes.

By the time it was over, a line had been drawn in the sand: science dug in on one side and built a fortress around itself; on the other, religious fundamentalists held firm to a literal interpretation of the Biblical creation story. Those who argued for dialogue, or for a more sophisticated understanding of the issue, found their voices increasingly drowned out in the public sphere.

[Note: The quotations from ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s talk at the Open Forum used in this article are taken from the Ella Cooper Papers in the National Bahá’í Archives, United States.]