DURING THE AMERICAN BICENTENNIAL year, in 1976, the Smithsonian Institution produced a special exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery titled Abroad in America: Visitors to the New Nation, 1776–1914. The exhibit, composed of large portraits accompanied by short essays, profiled more than fifty of the most noteworthy visitors to the United States during the nation’s first century and a half.

Some of them, such as José Martí of Cuba, or Swami Vivekananda and Rabindranath Tagore from India, had lodged their places in history as intellectual leaders of anti-colonial political struggles. Others became known as national political leaders: Georges Clemençeau of France, Domingo Faustino Sarmiento of Argentina, and the first Japanese delegation to America. Still others were popular literary or artistic figures: Charles Dickens, Antonín Dvořák, Giacomo Puccini, John Butler Yeats. Some were noteworthy because of their illuminating analysis or commentary, such as Frenchman Alexis de Tocqueville and the Scot James Bryce, whose books Democracy in America and The American Commonwealth, respectively, have become seminal works in American political science. Others were compelling because of their disparaging opinions of the nation, sometimes to the point of comedy, such as Harriet Martineau and Frances Trollope.

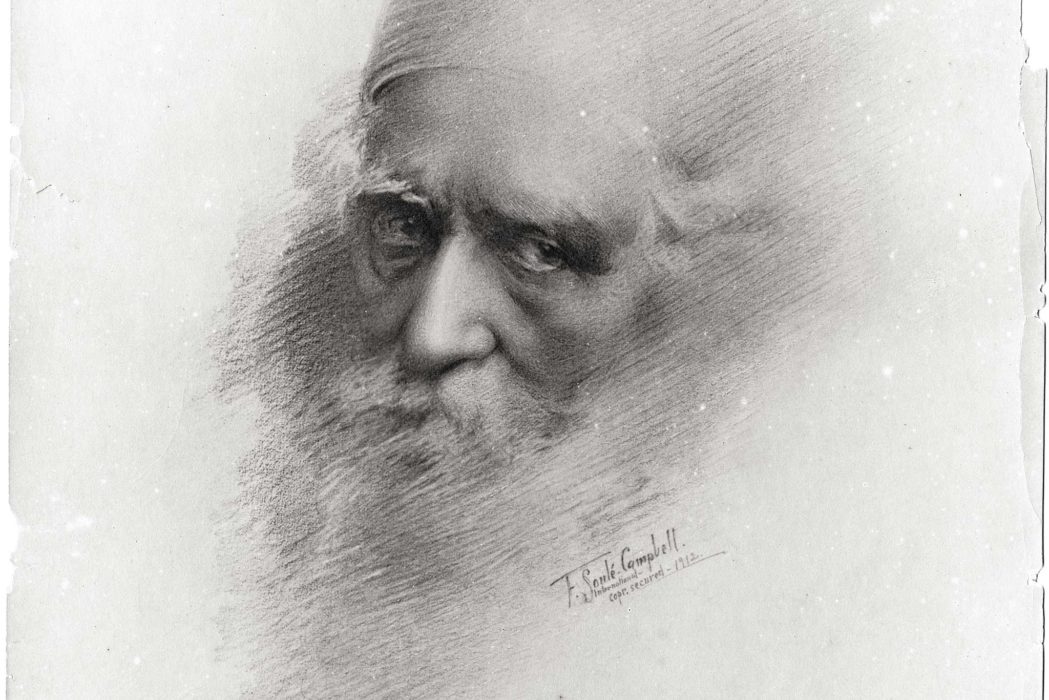

With the exception of Bryce, who served as Britain’s Ambassador to the United States from 1907 to 1913, none of these foreigners who traveled in America, I believe, have left more documentation about their visits than ‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Yet in 1976 ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s portrait did not appear in the Smithsonian’s exhibition. Around the world there are millions of people — from every country, language, and background — for whom ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s example is central to their lives. But by American historians he appears to have been left out.

Why?

I believe the reasons have to do partly with the way historians approach their craft and partly with the way ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s story has been told across the century.

Historians of the Progressive Era have always been hard pressed to decide which figures during that watershed period in modern American history were worth examining. “This may seem to be a strange topic of debate,”Arthur Link and Richard McCormick wrote in 1983, “but really it is not. Progressivism engaged many different groups of Americans, and each group of progressives naturally considered themselves to be the key reformers and thought that their own programs were the most important ones.” Historians, likewise, “have succeeded in identifying their reformers only by defining progressivism narrowly, by excluding other reformers and reforms when they do not fall within some specific definition. . . .”

The lenses that American historians have trained on the Progressive Era have simply not been focused on a visitor such as ‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Even as he addressed the central dilemmas facing the American nation, he never engaged in political controversies. Although he offered a challenging view of world order, he never became associated with nationalistic movements who rewrote their own national histories to place their thinkers and leaders at the center of historical action. American historians like Benjamin Parke De Witt, Richard Hofstadter, Robert Wiebe, John Higham, and Arthur Link weren’t looking for someone like an ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, and so, when they looked back at the vast historical evidence from 1912, they never saw him.

We can see, I believe, an inverted process at work in authors who have chosen to write about ‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Since the early years of the century, they have almost all been Bahá’ís, whose primary concern was to communicate stories designed to edify the faith of other Bahá’ís, not to present ‘Abdu’l-Bahá as an integrated voice in a mainstream American narrative. Over the past couple of decades, or so, this has begun to change, in the work of authors such as Robert Stockman and Gayle Morrison. An additional challenge has been that virtually all of the work produced about ‘Abdu’l-Bahá has been printed by Bahá’í publishing organizations, whose distribution outside Bahá’í circles is limited, instead of mainstream publishing houses.

Over the last eight months, we have attempted to establish a narrative about ‘Abdu’l-Bahá that embeds him in the rich context of American life in 1912, told in a language crafted for a broad audience. We have sought to present ‘Abdu’l-Bahá as an original voice, who engaged Americans of all kinds in conversations about the way they understood themselves and their place in the world, instead of primarily as a religious figure for a particular community. We have found that this approach reveals ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s American discourse to have been far more nuanced and complex than we imagined. Paradoxically, understanding how ‘Abdu’l-Bahá engaged deeply with the specifics of America in 1912, and placing him in the detailed context of time and place, makes him more relevant — not less — to the challenges America faces today.