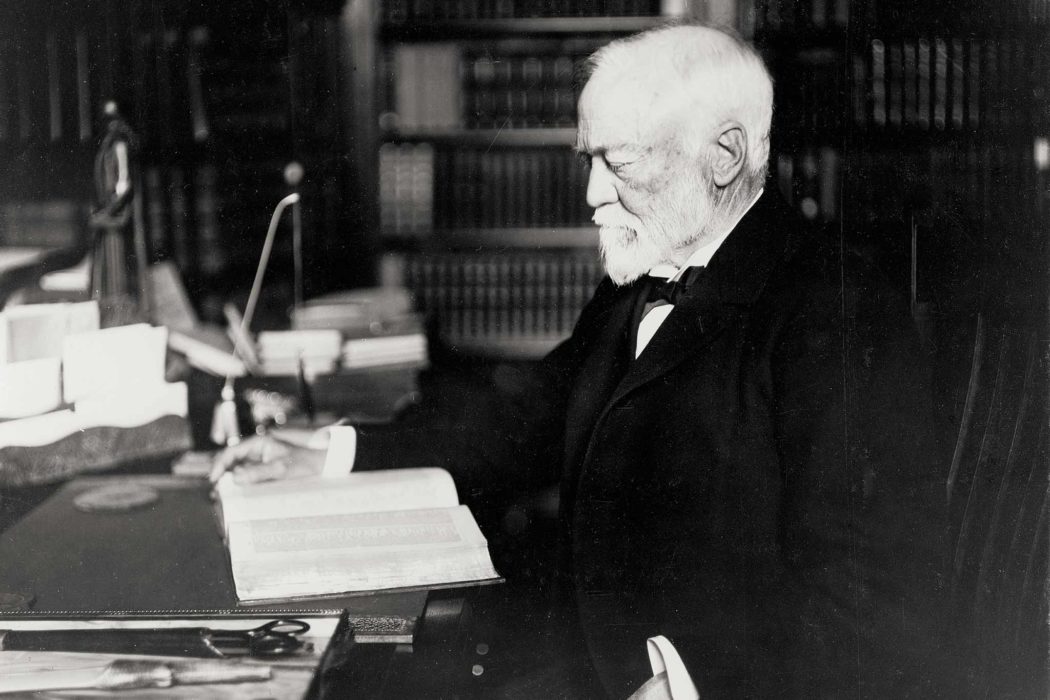

ANDREW CARNEGIE HAD SPENT a fortune on it. In 1910 he had doled out ten million dollars – that’s more than $230 million in today’s money – to set it up. We know it as the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Its board of directors included Columbia University president Nicholas Murray Butler, who had spoken before ‘Abdu’l-Bahá at the Lake Mohonk Conference on International Arbitration on May 14, as well as Albert Smiley, who hosted the conference at his hotel atop the Shawangunk Ridge in New Paltz.

Carnegie also recognized the centrality of religion to the success of the peace movement. Despite being lukewarm on organized religion himself, in 1914 he would spend another half a million dollars to endow the Carnegie Church Peace Union. Its thirty-person board of trustees was filled with Protestant, Catholic and Jewish leaders. He hoped it would mobilize the world’s churches and other religious and spiritual organizations to take moral leadership in the cause of international peace.

The peace movement in America had been intertwined with religion from its start. When ‘Abdu’l-Bahá addressed the International Peace Forum at Grace Methodist Episcopal Church on May 12, 1912, he was looking out over a crowd of Christian, and Jewish faithful. It was the same at his talk to the New York Peace Society on the following day – an institution bankrolled by Carnegie. On both occasions, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá alluded to Biblical prophecies regarding the inevitability of what he called the “Most Great Peace.”

Today, on the afternoon of May 28, 1912, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá was about to address the International Peace Forum for a second time — this time at the Metropolitan Temple at Seventh Avenue and 14th Street, where he had spoken to the suffrage meeting just eight days earlier.

Reverend J. Wesley Hill, president of the International Peace Forum and former pastor of the Metropolitan Temple, welcomed everyone. “This is a great occasion,” he began. “It is graced and honored by distinguished guests, representatives of the great International Peace Movement, who have acquired fame at home and abroad.”

There were over 1,000 of them in attendance that day, including two speakers who would share the program with ‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Reverend Lynch now led the Metropolitan Temple and would go on to become secretary of the Carnegie Church Peace Union. Rabbi Joseph Silverman ran America’s leading Reform Judaism congregation at Temple Emanu-El at Fifth Avenue and 65th Street on the Upper East Side, and was a major voice in the American peace movement. Both men had listened to ‘Abdu’l-Bahá at Lake Mohonk.

After the preamble, Reverend Lynch was the first to speak: “I do not intend to discuss any phases of the Peace question,” he said. “I don’t want to stand here and take your time when I know you want to listen to one who comes from the East.”

‘Abdu’l-Bahá, it seemed, was already a much-anticipated voice on the New York peace circuit.

“I have been exceedingly interested in the visit of Abdul-Baha to this country,” Reverend Lynch continued. “It may interest you to know where I first saw him. It was at Charles Grant Kennedy’s play, the ‘Terrible Meek.’” ‘Abdu’l-Bahá had attended the play, which depicts the Crucifixion, on the afternoon of April 19, just before he met with Kate Carew and went to the Bowery Mission.

The play, Lynch said, was meant “to show us that we are not to go about in this world with the smell of blood upon us, but we are in this world to carry blessing to mankind.”

“The last century,” Lynch concluded, “was the century of nationalism in religion, but this twentieth century is the century of universality in religion. All our great religions are beginning to spread throughout the world, and we are beginning to find that which is good in them all.”

“Now I welcome this great man today because he stands for all these things.”

Then ‘Abdu’l-Bahá rose to speak.

In tomorrow’s feature: ‘Abdu’l-Bahá speaks at the Metropolitan Temple, and argues that the binding power of true religion must lie at the heart of humankind’s hopes for peace.